| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 3, March 2022, pages 104-108

An Unusual Case of Cerebral Arteriovenous Malformation in Pregnancy

Cheryl Shumin Kowa, f , Liying Yangb, Wei Ching Tanb, Rachel Wei-Li Leongc, Yew Poh Ngd, Sridhar Arunachalame, Devendra Kanagalingamb

aYong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

bDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

cDepartment of Anaesthesiology, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

dDepartment of Neurosurgery, National Neuroscience Institute, Singapore, Singapore

eDepartment of Neonatal and Developmental Medicine, Singapore General Hospital, Singapore, Singapore

fCorresponding Author: Cheryl Shumin Kow, Yong Loo Lin School of Medicine, National University of Singapore, Singapore, Singapore

Manuscript submitted November 28, 2021, accepted January 25, 2022, published online March 5, 2022

Short title: A Case of Cerebral AVM in Pregnancy

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3862

| Abstract | ▴Top |

We present a case of a woman at 31 weeks and 3 days of gestation, who developed a sudden and severe headache and loss of vision in her left eye. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain revealed a subarachnoid bleed secondary to a right parieto-occipital arteriovenous malformation (AVM). She was conservatively managed and subsequently transferred to our institution for multidisciplinary care. The patient underwent a cesarean section at 34 weeks and 5 days of gestation followed by gamma knife surgery 6 days after. Cerebral AVMs, although relatively rare, have the propensity to cause potentially fatal outcomes. Neurological symptoms in a pregnant woman warrant investigations for early diagnosis and management, due to its associated morbidity and mortality. The management of cerebral AVMs in pregnancy is decided after weighing the benefits of treatment against the risk of bleeding. A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted due to the complexity of the condition.

Keywords: Cerebral arteriovenous malformation; AVM; Pregnancy; Obstetrics

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The prevalence of cerebral arteriovenous malformation (AVM) is estimated at approximately 0.01% of the general population [1], and the yearly hemorrhage rates of cerebral AVMs at 2-4% [2]. Most available studies suggest that the risk of hemorrhage from a cerebral AVM is unaltered in pregnancy, but this is controversial due to the inconsistency among the rates reported in literatures [2, 3]. Studies that suggest an increased risk of rupture in pregnancy postulate that it may be due to maternal hemodynamic changes and the influence of hormonal changes during pregnancy, affecting the structure of these vessels and rendering them more prone to rupture [1, 3, 4].

The typical presentation of a ruptured cerebral AVM includes headaches, seizures, muscle weakness, paralysis, vertigo, aphasia, and numbness [1], which may be mistaken for other disorders associated with pregnancy, such as migraine, pre-eclampsia, eclampsia, posterior reversible encephalopathy syndrome and cerebral venous thrombosis [5].

Intracranial hemorrhage from cerebral AVM is a rare complication of pregnancy, but if unrecognized, poses significant mortality and morbidity risks to both mother and fetus [1, 3]. It is essential that an accurate diagnosis is made so that treatment can be initiated promptly. In this case report, we present a case of a woman at 31 weeks and 3 days of gestation who developed a severe headache and loss of vision, later diagnosed with subarachnoid bleed secondary to cerebral AVM. We aim to discuss the special considerations in the management of cerebral AVMs in pregnancy, with specific emphasis on the anesthetic and obstetric care. This case also highlights the fact that neurological symptoms can vary depending on the site of the bleed and patients may present to clinical specialties other than neurology. A high index of suspicion for the condition is essential if severe headache is a predominant symptom.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

The patient was a 32-year-old woman, gravida 4, para 3. Her medical and family history was insignificant and without any history of hypertension, stroke or cerebral AVMs. She had no history of smoking, alcohol or drug abuse. Her obstetric history included three previous spontaneous vaginal deliveries, with gestational diabetes mellitus in her last pregnancy.

Her current pregnancy had been uneventful until presentation. At 31 weeks and 3 days of gestation, she developed a sudden and severe headache and a loss of vision in her left eye, which prompted her to seek medical advice from an ophthalmologist.

She described the headache as left sided, throbbing in nature, 10/10 on the Numerical Rating Pain Scale, exacerbated by coughing and lying down and associated with photophobia. Prior to this episode, she had experienced headaches for many years, which had been increasing in frequency for the past year (3 - 4 times a week).

The monocular left visual loss was described as complete blindness. On physical examination, her left eye’s visual acuity was poor (light perception was intact but she was unable to count fingers or identify hand movement). Right eye visual acuity and visual fields were intact.

Diagnosis

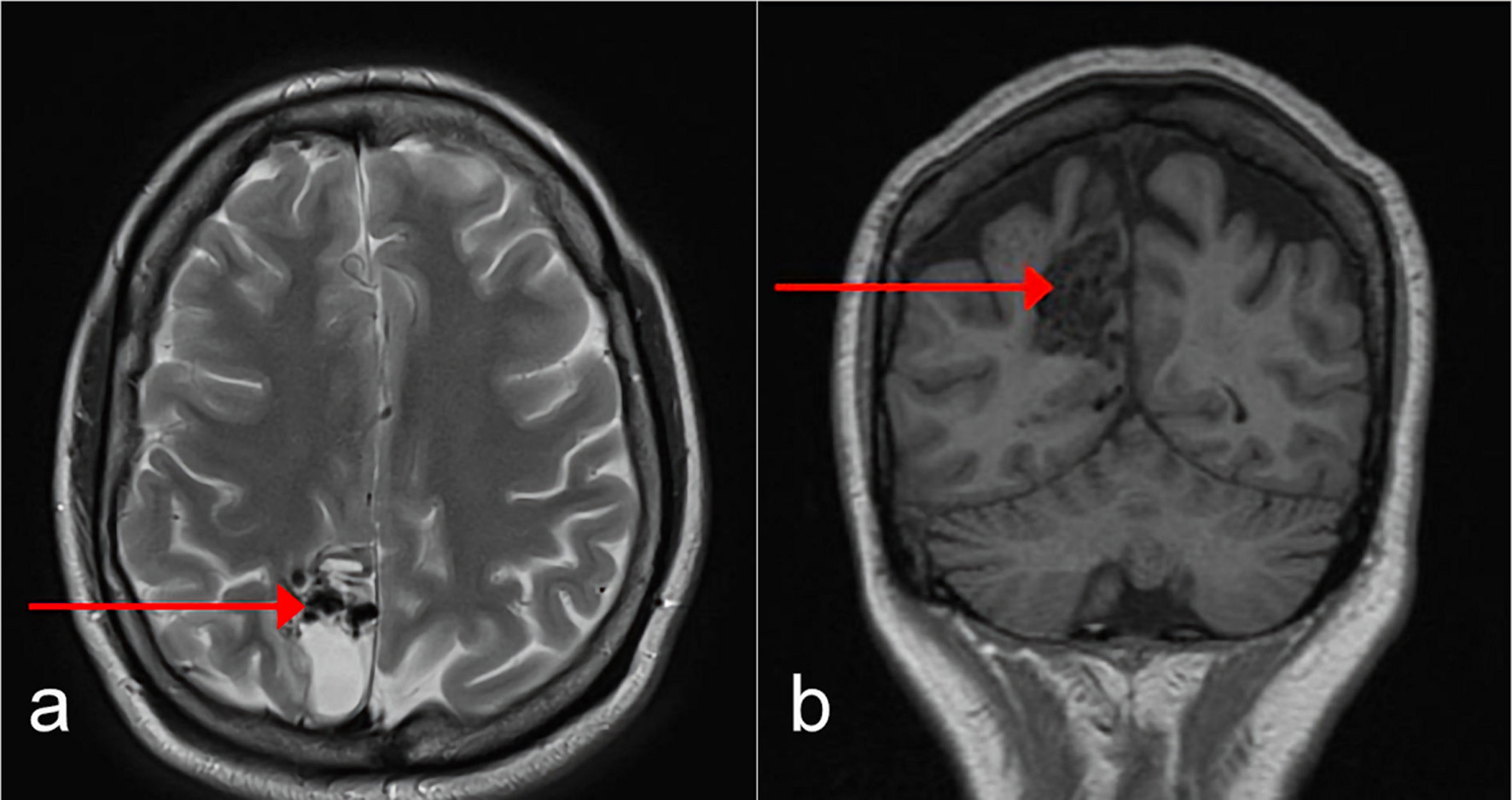

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain was performed, which confirmed a right parieto-occipital AVM, causing subarachnoid hemorrhage (Fig. 1). The patient’s left monocular visual loss may not be fully explained by her right parieto-occipital AVM as right occipital lobe pathology will typically cause a left homonymous hemianopia visual defect, rather than monocular visual loss. The patient was hence reviewed by an ophthalmologist, who promptly ruled out any obvious intraocular pathology. Given the patient’s stable neurological status, and the assuring status of the fetus, she was conservatively managed and discharged after 3 days before transfer to our institution for further care.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Axial (a) and coronal (b) MRI of the brain performed at our institution demonstrated a nidal type right parietal AVM (as shown by arrows). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; AVM: arteriovenous malformation. |

Treatment

At our institution, multidisciplinary meetings were held involving the relevant departments: obstetrics and gynecology, neurosurgery, anesthesia, and neonatology. Given the patient’s stable neurological status, the plan was made to deliver the fetus by elective lower segment cesarean section (LSCS) at 35 weeks, with administration of steroids for fetus lung maturation. This gestation was felt to be an optimal compromise in our efforts to reduce the risk of a subsequent intracranial bleed during pregnancy while minimizing the risks of prematurity in the fetus.

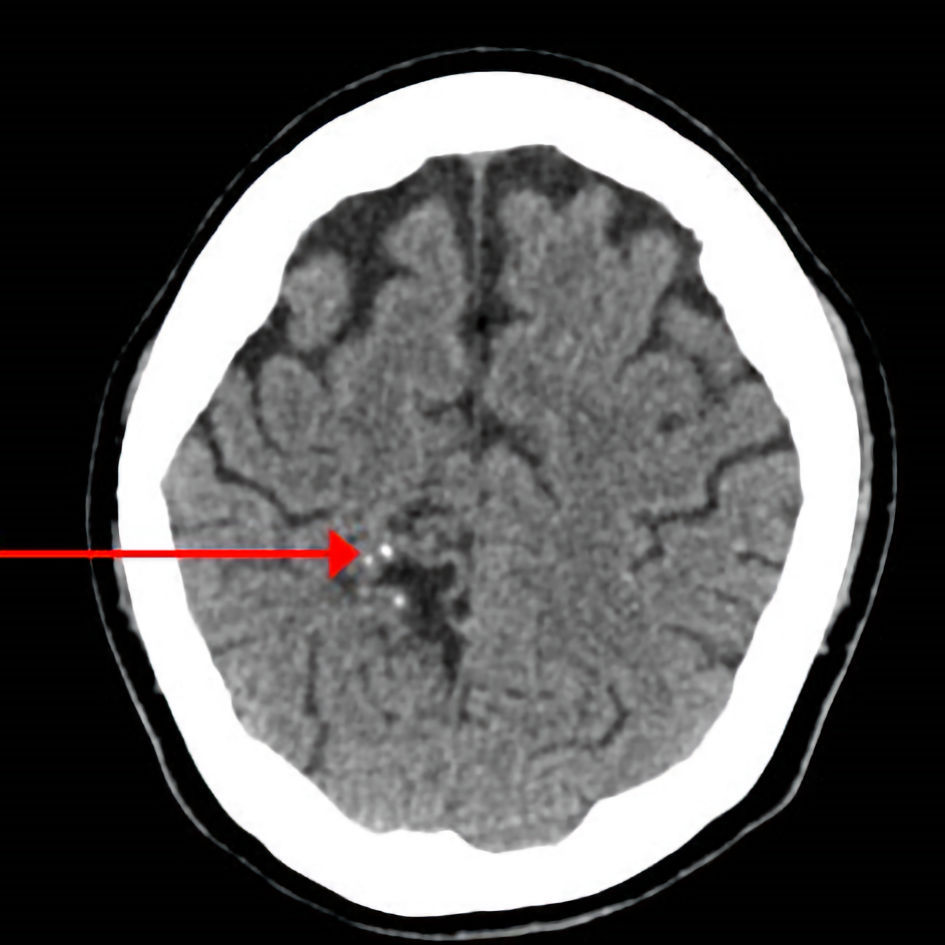

At 34 weeks and 5 days gestational age, the patient reported a persistent worsening headache. Computed tomography (CT) scan of the brain was performed, and no acute bleed was found (Fig. 2). However, there were concerns that if the headache continued to worsen or persist, repeated imaging might be a challenge due to radiation risks to the fetus. Furthermore, the prognosis for the fetus was favorable given the gestational age and the completion of steroids. As such, the decision was made by the multidisciplinary team for delivery by LSCS under regional anesthesia the following morning.

Click for large image | Figure 2. CT of the brain performed in view of patient’s persistent worsening headache revealed no acute intracranial hemorrhage or large territorial infarct. A few foci of isodensity with foci of calcifications (arrow) were seen in the right parietal lobe, associated with adjacent gliosis, and likely related to underlying vascular malformation. CT: computed tomography. |

A risk of re-bleeding during the LSCS was also considered, which might require neurosurgery intervention. Conversion from regional to general anesthesia was also anticipated should the epidural process be difficult, so as to avoid risks of a dural puncture.

Follow-up and outcomes

The delivery was uncomplicated and the fetus was delivered at 34 weeks and 6 days, with Apgar scores of 8 and 9 at 1 and 5 min, respectively. The patient also opted for sterilization by way of tubal occlusion during the same procedure.

Postoperative CT of the brain showed no new intracranial hemorrhage. The patient returned to the neurosurgical intensive care unit for recovery postoperatively. She subsequently underwent a gamma knife procedure for the AVM after 6 days.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Cerebral AVM hemorrhage is a rare but grave complication of pregnancy, with a 28% maternal mortality and 14% fetus death rate [6]. The risk of re-bleeding in the same pregnancy has been cited to be as high as 27-30% [3, 4] far greater than the re-bleeding risk in the non-gravid population of 2-6% per annum [7]. As such, the rupture of a cerebral AVM during pregnancy necessitates immediate attention in preserving maternal life and fetus well-being.

As a common benign complaint in pregnancy, headache is often not considered as a sign of serious disease until neurological complications develop [5]. It is critical that neurological symptoms in pregnancy are addressed promptly given that neurological diseases contribute to approximately 20% of maternal deaths [5]. In the case described, the patient presented with monocular visual loss and worsening of a longstanding headache. MRI of the brain was performed and diagnosed a subarachnoid hemorrhage secondary to an AVM bleed.

In the setting of concerns for spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage, the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association recommends rapid non-contrast CT or MRI [2]. In pregnancy, radiological imaging other than ultrasound is usually avoided unless there is a clearly defined indication, and precautions are taken to limit fetus exposure to ionizing radiation. However, concerns about fetus exposure to radiation should not compromise maternal well-being [8].

CT is very sensitive for identifying acute intracranial hemorrhage. In pregnancy, CT of the head can be safely performed with lead shielding of the abdomen and pelvis. Fetus exposure to ionizing radiation from CT of maternal head is extremely low (< 0.005 mGy) and the risk to the fetus is likely considerably less than the risk to both fetus and mother from an acute neurological condition [8]. The safety of MRI in pregnancy is well established. MRI is highly specific for the detection of intracranial vascular malformations. However, it may not be as sensitive as CT in the detection of an acute subarachnoid bleed [9].

The decision on imaging modality should be made after consideration of patient’s clinical status and tolerability, the urgency for evaluation as well as the differential diagnosis in mind. There should be a low threshold for neurological imaging in pregnancy due to the higher risk of complications, regardless of modality used.

The indications for surgical intervention for a cerebral AVM in the gravid patient should be based on neurosurgical rather than obstetric considerations. Different management strategies have been reported to manage cerebral AVMs in pregnancy as the exact threshold for the decision to operate on a pregnant woman with a known unruptured AVM is debatable.

It is vital for definitive treatment to be considered once an AVM hemorrhage has occurred due to the greater risk of re-bleeding after an initial AVM rupture [1, 3]. There are several options in definitively treating cerebral AVMs, with case reports of neurosurgical treatment [2, 4], stereotactic radiosurgery [4] and endovascular embolization [2] documented. Attributes of the AVM, stage of pregnancy, urgency for definitive treatment as well as the risks of intervention should be considered in this decision-making process.

Neurosurgical treatment for cerebral AVM bleeding is indicated if intracranial hematoma causes worsening neurological symptoms or cerebral herniation [6]. If the AVM is completely resected during pregnancy, the mode of delivery can be determined based on the obstetrical indications. However, this has to be balanced with the risks of surgical complications from neurosurgery, which may impact both mother and the fetus [1, 6]. If the ruptured AVM is managed conservatively, with resection of the AVM after delivery, this may expose the patient to continued risk of hemorrhage and re-bleeding throughout the pregnancy [1].

Radiosurgery is an alternative to neurosurgery, especially so in parts of the brain not readily accessible. Its most important limitation is that complete eradication of the AVM occurs in approximately 80-84.1% of patients only 2 - 3 years after the procedure [1]. This exposes the patient to a 2-year latency period with the AVM still present in the cerebral vasculature, and therefore still has the potential to hemorrhage, making protection from AVM hemorrhage impossible during the span of a 9-month pregnancy [1]. Radiosurgery during pregnancy also poses an inherent risk of fetus exposure to radiation [3], which may cause spontaneous abortion in early conception, fetus malformations and increased cancer susceptibility [1].

Endovascular embolization has been increasingly used in the treatment of AVMs in the general population, either as a stand-alone treatment or used prior to surgical resection [2]. In pregnancy, the fluoroscopy component of endovascular procedures also presents a potential risk to the fetus for excessive radiation exposure and should be minimized [1].

Our patient underwent radiosurgery post-LSCS because there was no new intracranial hemorrhage. If there was a life-threatening acute hemorrhage, an emergency craniectomy and evacuation of hematoma would have been performed first, followed by an emergency LSCS and the complete excision of the AVM performed electively after the delivery. From the obstetrical point of view, lifesaving procedures should be performed first if there is risk to maternal life. The delivery of the fetus will only be considered once maternal status has been stabilized.

In terms of obstetric management, decisions have to be made regarding mode and timing of delivery, and the choice of anesthesia during labor. There are differing opinions on whether a cesarean section is necessary in pregnant women with cerebral AVMs [1], with reports of successful vaginal delivery without adverse outcomes [2, 10]. Cesarean section has been advocated as a means to avoid the hemodynamic changes of intracranial vascular pressure associated with uterine contractions and Valsalva maneuvers of labor in induction of labor and vaginal delivery [10].

The choice of anesthesia used for the cesarean section of a pregnant woman with a cerebral AVM is made to maintain a stable cardiovascular system, but due to the rarity of this condition, no consensus exists. Regional anesthesia could be preferred over general anesthesia because it avoids the hemodynamic stress associated with laryngoscopy, intubation and extubation during general anesthesia [11]. The neurological status of the patient can also be monitored under regional anesthesia. However, there is a risk of accidental dural puncture, which may increase the risk of the AVM bleed and cerebral herniation if a raised intracranial pressure is already present. Our eventual approach in this patient was for epidural anesthesia with a low threshold for conversion to general anesthesia, in the event of technical difficulty. In recognition of the absence of a clear consensus on mode of delivery and type of anesthesia, we involved the patient and her partner in the decision-making process. The different options, their potential risks and benefits were discussed before agreeing on an individualized plan for management.

Learning points

Cerebral AVMs have the propensity to cause significant mortality and morbidity to both mother and fetus. Timely recognition of signs and symptoms of a ruptured cerebral AVM in pregnancy is crucial for optimal outcomes. A multidisciplinary approach should be adopted due to the complexity of the condition, involving obstetrics and gynecology, neurosurgery, anesthesia, and neonatology.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to declare.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Author Contributions

CSK, DK contributed to the conception, writing, and editing of the case report. DK, LY, WCT, RWL, YPN and SA managed the case and conceptualized the case report. All authors commented on the final paper and have approved the final version.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

AVM, arteriovenous malformation; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; LSCS, lower segment cesarean section; CT, computed tomography

| References | ▴Top |

- Agarwal N, Guerra JC, Gala NB, Agarwal P, Zouzias A, Gandhi CD, Prestigiacomo CJ. Current treatment options for cerebral arteriovenous malformations in pregnancy: a review of the literature. World Neurosurg. 2014;81(1):83-90.

doi pubmed - Sappenfield EC, Jha RT, Agazzi S, Ros S. Cerebral arteriovenous malformation rupture in pregnancy. BMJ Case Rep. 2019;12(7):e225811.

doi pubmed - Trivedi RA, Kirkpatrick PJ. Arteriovenous malformations of the cerebral circulation that rupture in pregnancy. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2003;23(5):484-489.

doi pubmed - Gross BA, Du R. Hemorrhage from arteriovenous malformations during pregnancy. Neurosurgery. 2012;71(2):349-355; discussion 355-346.

doi pubmed - Hosley CM, McCullough LD. Acute neurological issues in pregnancy and the peripartum. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(2):104-116.

doi pubmed - Lv X, Liu P, Li Y. The clinical characteristics and treatment of cerebral AVM in pregnancy. Neuroradiol J. 2015;28(3):234-237.

doi pubmed - Wilkins RH. Natural history of intracranial vascular malformations: a review. Neurosurgery. 1985;16(3):421-430.

doi pubmed - Dineen R, Banks A, Lenthall R. Imaging of acute neurological conditions in pregnancy and the puerperium. Clin Radiol. 2005;60(11):1156-1170.

doi pubmed - Josephson CB, White PM, Krishan A, Al-Shahi Salman R. Computed tomography angiography or magnetic resonance angiography for detection of intracranial vascular malformations in patients with intracerebral haemorrhage. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;9:CD009372.

doi pubmed - Horton JC, Chambers WA, Lyons SL, Adams RD, Kjellberg RN. Pregnancy and the risk of hemorrhage from cerebral arteriovenous malformations. Neurosurgery. 1990;27(6):867-871; discussion 871-862.

doi pubmed - Yih PS, Cheong KF. Anaesthesia for caesarean section in a patient with an intracranial arteriovenous malformation. Anaesth Intensive Care. 1999;27(1):66-68.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.

This journal follows the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (

This journal follows the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (