| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 2, Number 6, December 2011, pages 255-259

Late Onset Flap Scarring After Laser in Situ Keratomileusis

Faik Orucoglua, c, Abraham Solomonb, Joseph Frucht-Peryb

aIstanbul Surgery Hospital, Ferah sok no 18, Nisantasi, Istanbul 34365, Turkey

bDepartment of Ophthalmology, Hadassah–Hebrew University Medical Center Jerusalem, Israel

cCorresponding author: Faik Orucoglu, Kudret Eye Hospital, Sarayardi no 1, Kadikoy, Istanbul 34277, Turkey

Manuscript accepted for publication August 10, 2011

Short title: Late Onset Flap Scarring

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc279w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

A 55-year-old man had uneventful simultaneous LASIK. Seven months postoperatively, the patient came with complaints of a decrease in vision, photophobia, tearing, discomfort, and red eye during the last 2 weeks in the left eye. Suspicion was foreign body hit. Despite steroid treatment, the clinical outcome didn’t improve. Eight months postoperatively, slit-lamp examination revealed thinning and scarring in the center of the flap in the central cornea. The left eye’s best corrected visual acuity was 20/32. The patient underwent a surgical procedure of trephining of the scarred flap and using Mitomycin C 0.02%. At the final examination after 18 months the BCVA was 20/25. This is the first report on late central corneal scarring after LASIK. Trephinization of the scarred flap can restore visual acuity.

Keywords: Late onset flap scarring; Laser in situ keratomileusis

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK) is performed worldwide with increasing frequency, for the correction of myopia, hyperopia and astigmatism. The vast increase in the number of LASIK procedures causes different complications by themselves. Reports show postoperative LASIK complication rates from 0.9% to 7.2 % [1-4]. Postoperative complications such as dislocated, wrinkled or distorted flaps, epithelial defects, epithelial ingrowth and inflammatory reactions are relatively well known. In contrast to photorefractive keratectomy (PRK) central corneal opacities are rarely seen after LASIK procedure. In this report we describe a case with late central corneal scarring after LASIK.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 55-year-old man was evaluated for laser correction of mixed myopic astigmatism. The preoperative best spectacle-corrected visual acuity (BCVA) was 6/6 in both eyes with manifest refractions of +0.50 - 1.75 × 78 in the right eye and +0.25 - 1.75 × 70 in the left eye. Keratometry was 44.70 × 112/43.94 D × 22 in the right eye and 44.58 × 0/44.52 D × 90 in the left eye. The corneal topography was within normal limits in both eyes. Ultrasonic central corneal pachymetry was 570 mm in the right eye and 565 mm in the left eye. No abnormalities were observed during a slit-lamp examination.

In September 4, 2003 the patient underwent bilateral LASIK (JFP) using a Technolase 217-z excimer laser (Bausch and Lomb, Irvine, CA) and 6.0 mm optical zone treatment. Flap cut was performed with a Hansatome microkeratome (Bausch and Lomb Miami, FL) using the 160 µm head and 9.5 mm suction ring. The total ablation depth was 37 µm in the right eye and 34 µm in the left eye. The flap was well positioned in both eyes with a clean interface. After repositioning of the flap, a soft contact lens was placed on the eye. The postoperative regimen included topical levofloxacin, 4 times a day for one week, and topical prednisolone acetate, 4 times a day for two weeks. The surgical procedure and the postoperative course were uneventful and unremarkable.

In the first postoperative month, the uncorrected visual acuity (UCVA) was 6/5 in the right eye and 6/6 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination revealed a well-healed flap with clear interface in both eyes.

The patient returned 7 months after LASIK with complaints of a decrease in vision, photophobia, tearing, discomfort, and red eye during the last 2 weeks in the left eye. He suspected that he had a foreign body on his eye. His UCVA was 6/6.6 in the left eye. Slit-lamp examination showed a central flap swelling and opacification in the left eye. The epithelium was intact. The patient received drops of Dexamethasone phosphate 0.1% and Ofloxacin QID.

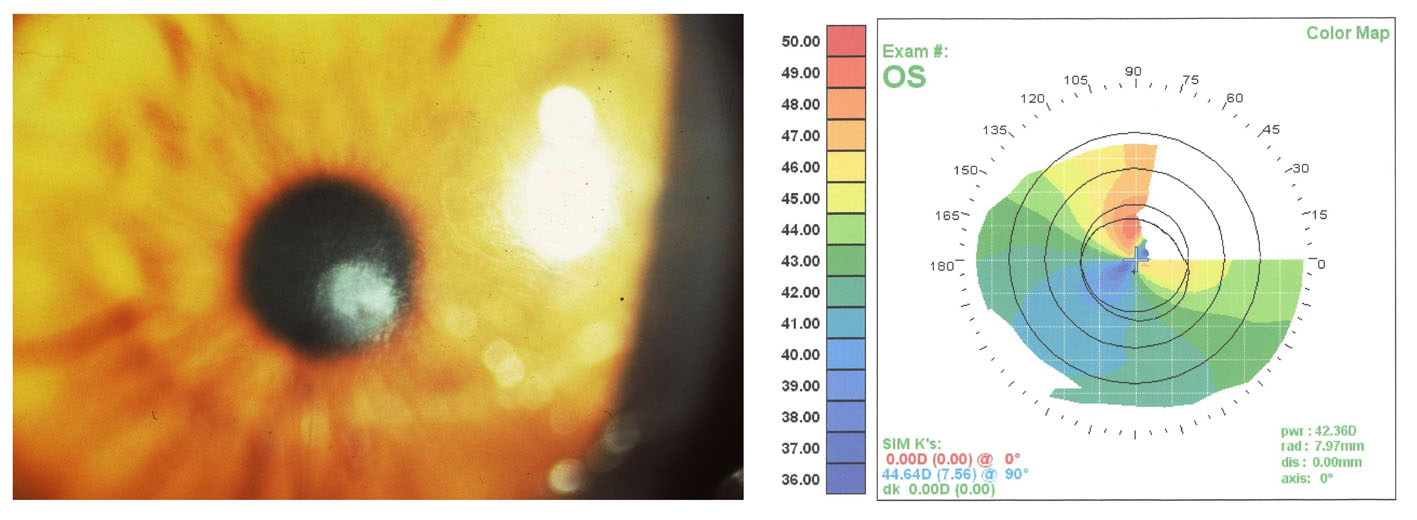

The subepithelial haze got worse. Eight months postoperative, the left eye UCVA was 6/12 and it improved to 6/9 with a refraction of plano/ -0.50 × 25. Slit-lamp examination revealed thinning and scarring in the center of the flap in the central cornea; and corneal topography showed irregularity in the left eye (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Eye with late post-LASIK interface scarring with BCVA of 6/9. Computerized corneal topography shows irregularity induced by scarring. |

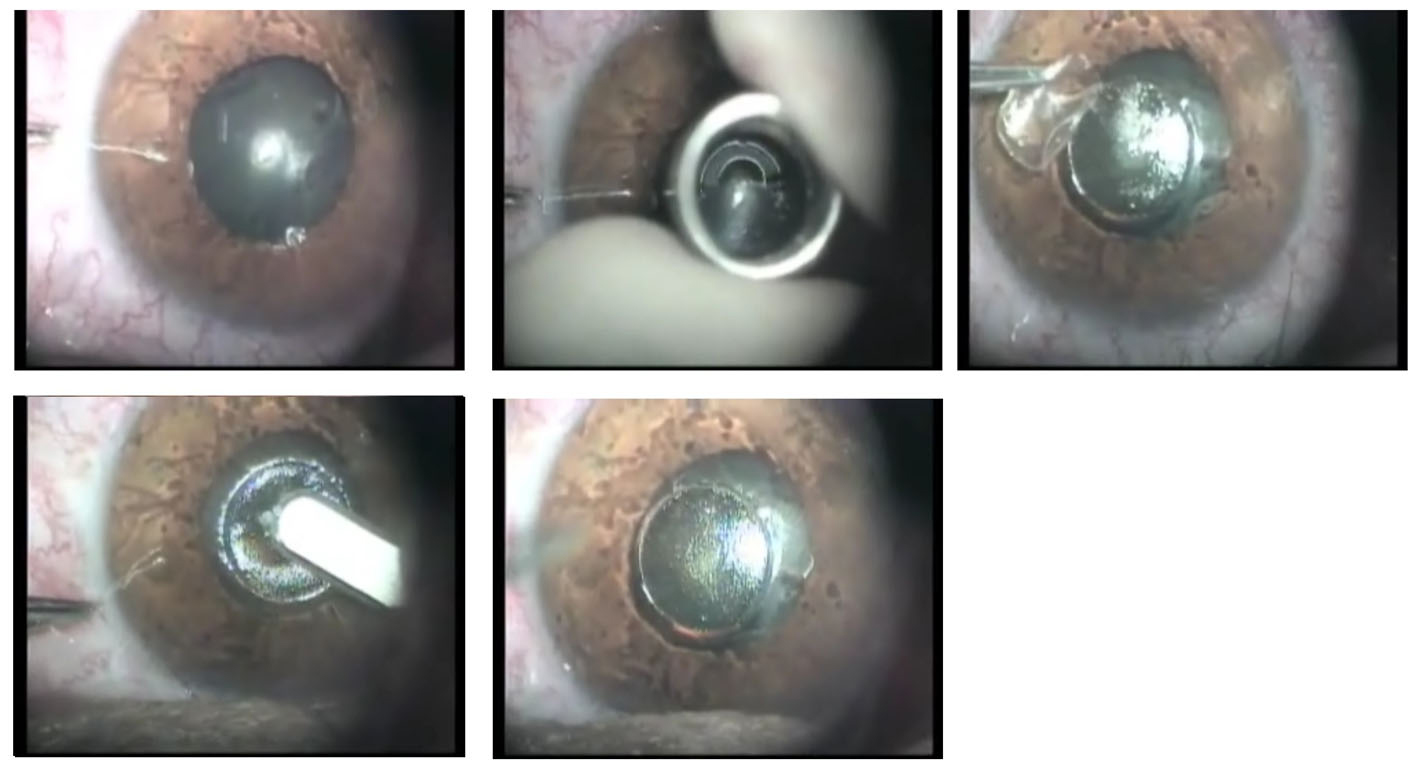

After informed consent was obtained, the patient underwent surgical procedure. Under topical anesthesia, the centre of the scarred flap was trephined using 4 mm trephine and cut with scissors. Mitomycin C (MMC) 0.02% was applied for 1 minute. (Fig. 2). Debrited tissue was sent for histological evaluation. A bandage soft contact lens was placed on the eye and patient received topical Dexamethasone phosphate and Gentamicin.

Click for large image | Figure 2. Preoperative view, trephination, removing epithelium, debridment of scarred tissue and postoperative view. |

Postoperatively, the UCVA in the left eye remained 6/12 but patient did not have photophobia. Boimicroscopy revealed haze in the central cornea.

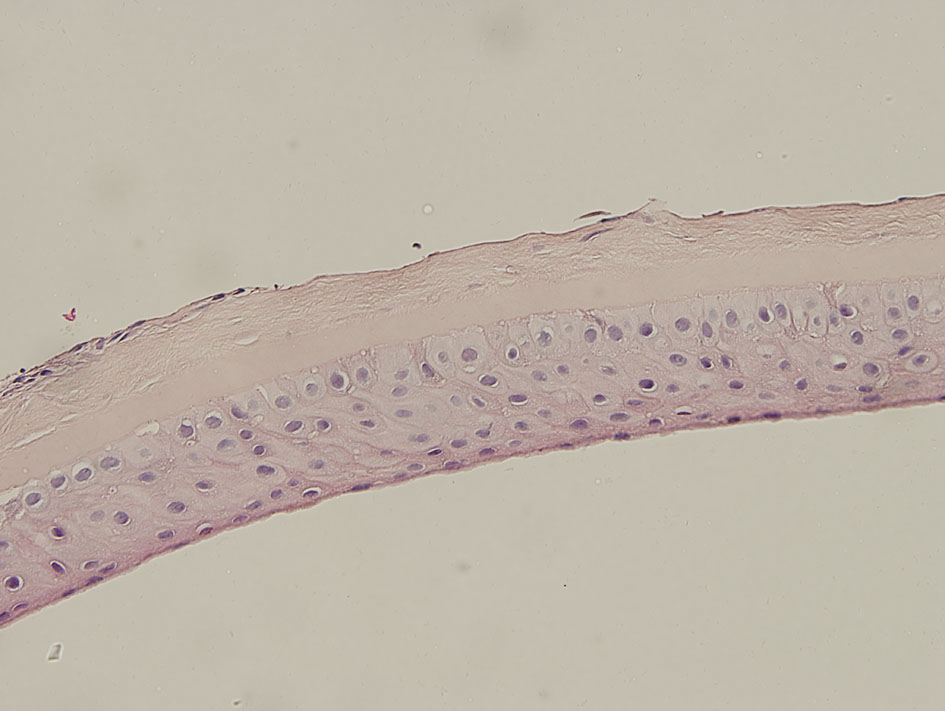

The histological examination of the excised flap revealed subepithelial scarring and the Bowmans layer was missing (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. The histological examination showing subepithelial scarring and the Bowmans layer was missing. |

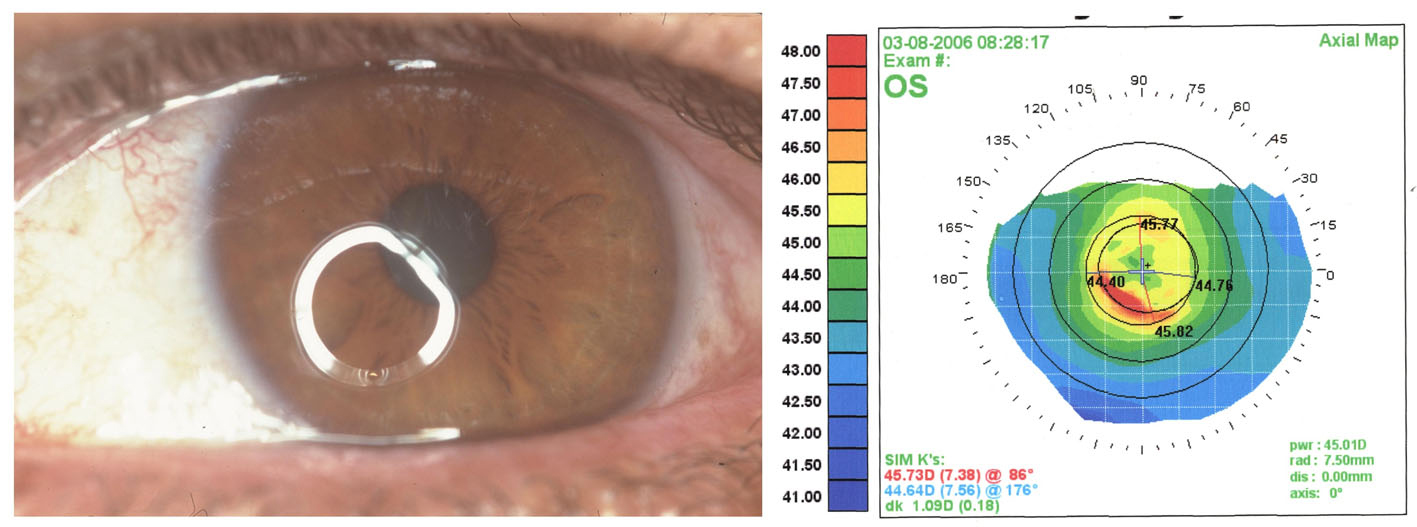

At the final examination after 18 months the UCVA was 6/9 improving to 6/7.5 with -0.25/1.00 × 180 and corneal topography improved. There was superficial corneal haze in the central 3 mm of the cornea (Fig. 4). The patient has mild glare at night time and didn’t want additional enhancement.

Click for large image | Figure 4. Same eye after keratectomy with MMC; BCVA is 6/7. Irregularity improved on topography. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Subepithelial corneal scarring is one of the complications of PRK [5]. Scarring after PRK has been associated with greater amounts of treatment, smaller ablation zones, male gender, ablations deeper than 50 µm, and early discontinuation of topical steroids [6]. Corneal haze after PRK gradually develops at the epithelial-stromal junction: starting one week postoperatively, peaking within 3 months (mean grading, 1.03), and declines slowly thereafter [6].

The most important advantage of LASIK over PRK is the lack of corneal haze [7]. Haze after LASIK rarely occurs. Histopatologic studies of corneal healing in rabbits show that the wound-healing reaction occurs at the flap margins, leaving the central corneal zone clear after LASIK [8]. Similar results have been described in human eyes [9, 10]. The epithelium and Bowman’s layer are not affected at the center of cornea, so, therefore, leads to clear visual axis.

Late onset significant haze and scarring in the flap were observed in our case. Late onset corneal haze (LOCH) is described after PRK with incidence of 0.6-4% [11-13]. LOCH after PRK usually appears 4 months after surgery with peaked mean time of 7.4 months [12]. It causes visual impairment and topographical abnormalities and correlates with the amount of attempted correction and UV radiation exposure [13-15].

Keratinocytes, fibroblast growth factor and transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β) regulate the corneal stromal wound-healing process after excimer laser keratectomy [16]. It has been shown that the increased expression of TGF-β and TGF-β receptors in keratocytes play a role in the activation and proliferation of keratocytes and extracellular matrix production, leading to fibroblast transformation and haze formation after the excimer laser keratectomy [17].

Minna Vesaluoma et al [18] found that after LASIK treatment keratocyte activation was greatest on the third postoperative day and that after 6 months the mean density anterior layer of flap keratocytes was decreased. On the other hand Takuji Kato et al [19] showed that wound healing process continues in rabbit’s corneas even 9 month after LASIK.

Keratocyte activation induced by LASIK was of short duration compared with that reported after photorefractive keratectomy [18]. Stromal wound healing process after LASIK is minimal, except in the wound margin [20].

Cases of haze after epithelial abrasion in post-LASIK surgery have been described [21, 22]. Significant haze which affects the vision developed after flap manipulation with epithelial debridement for treatment of post LASIK striae [23]. Post LASIK corneal trauma and foreign body removal induce DLK. Late-onset interface inflammation post-traumatic flap injury after LASIK is associated with neutrophils in tear fluid [24]. Epithelial damage releases more cytokines and induces keratocyte apoptosis and myofibroblast activation after refractive procedures [25]. The intact epithelium plays an important role in preventing subepithelial haze and differentiation of myofibroblasts in corneal wound healing [26]. These studies indicate that ocular trauma may induce significant inflammation.

Cases of stromal haze were reported 1 to 9 months after LASIK surgery or retreatment [27-30]. However, 55.6% of eyes had previous diffuse lamellar keratopathy (DLK) on the first postoperative day and no patient had lost lines of BCVA or complained of reduced vision [27]. Severe haze was reported after LASIK in cases with previous PRK and vice versa [28-30].

In our case severe haze was observed 7 months after LASIK treatment, probably due to trauma to the flap by foreign body. The patient showed up at the clinic, 2 weeks after the trauma. The patient didn't receive any treatment during this time. It is possible that patient had marked intrastromal inflammation, diffuse lamellar keratitis (DLK) like syndrome which caused marked activation of stromal keratocytes and lead to a process which could not be stopped by late treatment with topical steroids. The flap became thinner and the haze denser despite the use of topical steroids. UCVA decreased to 6/12. Central flap was excised and MMC 0.02% was used. After the partial flap excision the patient stopped complaining of photophobia, tearing and discomfort. The UCVA was 6/9 improvement to 6/7.5 due to irregular astigmatism and moderate haze that developed in the stroma during the following months.

We assume that in our case ocular surface trauma caused severe inflammatory process which induced flap scar formation. Despite the fact that we removed the flap we still ended up with some degree of stromal scarring. However this scarring is easier to explain as the bowman membrane was missing. Although we lost 1 - 2 lines of BCVA, there was a clinically cessation of photophobia, tearing and discomfort and the patient gained improved vision. It is questionable whether excising all the flap could provide better vision as it could diminish the extent of the postoperative astigmatism. There is a further potential to improve the vision in our patient by doing PRK enhancement or removal of the rest of flap.

In conclusion we describe a case of late onset corneal scarring after LASIK treatment which most probably due to susceptible foreign body trauma.

Conflict of Interest

The authors do not have any proprietary interest in the products and drugs mentioned in this manuscript.

| References | ▴Top |

- Knorz MC. Flap and interface complications in LASIK. Curr Opin Ophthalmol. 2002;13(4):242-245.

pubmed doi - Gimbel HV, Penno EE, van Westenbrugge JA, Ferensowicz M, Furlong MT. Incidence and management of intraoperative and early postoperative complications in 1000 consecutive laser in situ keratomileusis cases. Ophthalmology. 1998;105(10):1839-1847; discussion 1847-1838.

pubmed - Stulting RD, Carr JD, Thompson KP, Waring GO, 3rd, Wiley WM, Walker JG. Complications of laser in situ keratomileusis for the correction of myopia. Ophthalmology. 1999;106(1):13-20.

pubmed doi - Petersen H, Seiler T. Laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK). Intraoperative and postoperative complications. Ophthalmologe. 1999;96(4):240-247.

pubmed doi - Amano S, Shimizu K. Excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy for myopia: two-year follow up. J Refract Surg. 1995;11(3 Suppl):S253-260.

pubmed - Caubet E. Course of subepithelial corneal haze over 18 months after photorefractive keratectomy for myopia [corrected]. Refract Corneal Surg. 1993;9(2 Suppl):S65-70.

pubmed - Pallikaris IG, Siganos DS. Excimer laser in situ keratomileusis and photorefractive keratectomy for correction of high myopia. J Refract Corneal Surg. 1994;10(5):498-510.

pubmed - Wilson SE, Mohan RR, Hong JW, Lee JS, Choi R. The wound healing response after laser in situ keratomileusis and photorefractive keratectomy: elusive control of biological variability and effect on custom laser vision correction. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119(6):889-896.

pubmed - Latvala T, Barraquer-Coll C, Tervo K, Tervo T. Corneal wound healing and nerve morphology after excimer laser in situ keratomileusis in human eyes. J Refract Surg. 1996;12(6):677-683.

pubmed - Vesaluoma MH, Petroll WM, Perez-Santonja JJ, Valle TU, Alio JL, Tervo TM. Laser in situ keratomileusis flap margin: wound healing and complications imaged by in vivo confocal microscopy. Am J Ophthalmol. 2000;130(5):564-573.

pubmed doi - Meyer JC, Stulting RD, Thompson KP, Durrie DS. Late onset of corneal scar after excimer laser photorefractive keratectomy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1996;121(5):529-539.

pubmed - Kuo IC, Lee SM, Hwang DG. Late-onset corneal haze and myopic regression after photorefractive keratectomy (PRK). Cornea. 2004;23(4):350-355.

pubmed doi - Stojanovic A, Nitter TA. Correlation between ultraviolet radiation level and the incidence of late-onset corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(3):404-410.

pubmed doi - Tosi GM, Baiocchi S, Caporossi T. Late corneal scarring after retinal detachment surgery 42 months after photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(5):1124-1126.

pubmed doi - Lipshitz I, Loewenstein A, Varssano D, Lazar M. Late onset corneal haze after photorefractive keratectomy for moderate and high myopia. Ophthalmology. 1997;104(3):369-373; discussion 373-364.

pubmed - Jester JV, Petroll WM, Cavanagh HD. Corneal stromal wound healing in refractive surgery: the role of myofibroblasts. Prog Retin Eye Res. 1999;18(3):311-356.

pubmed doi - Kaji Y, Soya K, Amano S, Oshika T, Yamashita H. Relation between corneal haze and transforming growth factor-beta1 after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(11):1840-1846.

pubmed doi - Vesaluoma M, Perez-Santonja J, Petroll WM, Linna T, Alio J, Tervo T. Corneal stromal changes induced by myopic LASIK. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2000;41(2):369-376.

pubmed - Kato T, Nakayasu K, Hosoda Y, Watanabe Y, Kanai A. Corneal wound healing following laser in situ keratomileusis (LASIK): a histopathological study in rabbits. Br J Ophthalmol. 1999;83(11):1302-1305.

pubmed doi - Park CK, Kim JH. Comparison of wound healing after photorefractive keratectomy and laser in situ keratomileusis in rabbits. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1999;25(6):842-850.

pubmed doi - Buhren J, Kohnen T. Stromal haze after laser in situ keratomileusis: clinical and confocal microscopy findings. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(9):1718-1726.

pubmed - Artola A, Ayala MJ, Perez-Santonja JJ, Salem TF, Munoz G, Alio JL. Haze after laser in situ keratomileusis in eyes with previous photorefractive keratectomy. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2001;27(11):1880-1883.

pubmed doi - Gressel MG, Belsole VL. Laser in situ keratomileusis flap tear during lifting for enhancement in the presence of post-photorefractive keratectomy corneal haze. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30(3):706-708.

pubmed doi - Carones F, Vigo L, Carones AV, Brancato R. Evaluation of photorefractive keratectomy retreatments after regressed myopic laser in situ keratomileusis. Ophthalmology. 2001;108(10):1732-1737.

pubmed doi - Buhren J, Kohnen T. Corneal wound healing after laser in situ keratomileusis flap lift and epithelial abrasion. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(10):2007-2012.

pubmed doi - Asano-Kato N, Toda I, Tsubota K. Severe late-onset recurrent epithelial erosion with diffuse lamellar keratitis after laser in situ keratomileusis. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2003;29(10):2019-2021.

pubmed doi - Kuo IC, Ou R, Hwang DG. Flap haze after epithelial debridement and flap hydration for treatment of post-laser in situ keratomileusis striae. Cornea. 2001;20(3):339-341.

pubmed doi - Asano-Kato N, Toda I, Fukumoto T, Asai H, Tsubota K. Detection of neutrophils in late-onset interface inflammation associated with flap injury after laser in situ keratomileusis. Cornea. 2004;23(3):306-310.

pubmed doi - Helena MC, Baerveldt F, Kim WJ, Wilson SE. Keratocyte apoptosis after corneal surgery. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1998;39(2):276-283.

pubmed - Nakamura K, Kurosaka D, Bissen-Miyajima H, Tsubota K. Intact corneal epithelium is essential for the prevention of stromal haze after laser assisted in situ keratomileusis. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85(2):209-213.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.