| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 3, Number 5, October 2012, pages 286-289

Gastric Perforation Caused by Acute Massive Gastric Dilatation: Report of a Case

Sung-Ui Junga, Seung-Hyun Leea, b, Byung-Kwon Ahna, Sung-Uhn Baeka

aDepartment of Surgery, Kosin University College of Medicine, Busan, Korea

bCorresponding author: Seung-Hyun Lee, Department of Surgery, Kosin University Gospel Hospital, 34 Amnam-dong, Seo-gu, Busan, 602-702, Korea

Manuscript accepted for publication April 4, 2012

Short title: Acute Massive Gastric Dilatation

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc635w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Gastric necrosis with perforation caused by acute gastric dilatation is an extremely rare presenting complication. We experienced a rare case of gastric perforation caused by acute massive gastric dilatation after a binge-eating episode. A 23-year old woman was admitted with a chief complaint of acute abdominal pain with severe abdominal distension after a heavy meal. She had no history of abdominal surgery. On computed tomography, the stomach and the duodenum were severely dilated with food content. There was no tumor in the peritoneal cavity. Despite conservative management, the patient’s symptoms were aggravated after 2 days and she underwent an emergent laparotomy. Laparotomy revealed that the stomach and the second portion of the duodenum were severely dilated. There was a small perforation with surrounding necrotic change on the fundus of the stomach. We performed decompression through a gastrotomy and bypass duodeno-jejunostomy. The patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful. Physicians should be aware that binge-eating habits may cause acute massive gastric dilatation in the absence of a typical eating disorder history.

Keywords: Acute gastric dilatation; Gastric perforation; Stomach

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Gastric perforation caused by acute gastric dilatation is an extremely uncommon complication. In most cases, acute gastric dilatation is encountered as a postoperative complication after abdominal surgery and in several disorders, such as anorexia nervosa and bulimia, psychogenic polyphagia, or trauma [1-3].

Acute massive gastric dilatation has been described as an extreme distention of the stomach, in which it occupies the abdomen from the diaphragm to the pelvis and from left to right [4]. Acute massive gastric dilatation can cause ischemia, necrosis, and perforation of the stomach. In most cases of acute massive gastric dilatation, surgery has been necessary to prevent or to treat the complications. Early diagnosis with prompt gastric decompression may avoid unnecessary laparotomy.

We present the case of a patient with gastric perforation caused by acute massive gastric dilatation occurring after a bingeeating episode.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 23-year old female patient presented to the emergency department with a chief complaint of abdominal pain and abdominal fullness after a heavy meal. She reported having a tendency to overeat when she felt emotional stress; however she had no history of consultation for eating disorders. Three days prior to binge-eating, she experienced a stressful event at work. On the day of admission, she had two bowls of steamed rice and 4 - 5 pieces of sweet potato for lunch. After lunch, she abruptly experienced abdominal pain and abdominal fullness. The symptoms were not improved after taking digestive medicines. She had no history of previous abdominal surgery. She had a habit of smoking a quarter of a pack per day for 3 years.

At admission, the patient’s height and weight were 160 cm and 37 kg. Her body mass index was 14.5. Her vital signs were normal with blood pressure at 100/60 mmHg, a pulse rate of 64 beats/min, a respiration rate of 24/min, and a body temperature of 35.5 °C. On physical examination, she had severe abdominal distension with dull percussion and mild abdominal tenderness in the epigastric region. Intestinal sounds were audible, but weak, and with decreased frequency. She had reported intermittent nausea, but without vomiting. Laboratory investigations revealed the following: hemoglobin, 13.1g/dL; hematocrit, 37.8%; white blood cell count, 11,700/uL; platelet count, 233 x 103/uL; serum protein, 6.7 g/dL; serum albumin 4.3 g/dL; total bilirubin, 0.6 mg/dl; alanine aminotranferase 29 IU/l; aspartate aminotransferase, 15 IU/L; creatinine, 0.7 mg/dl; serum Na, 141 meq/L, serum K, 3.7 meq/L.

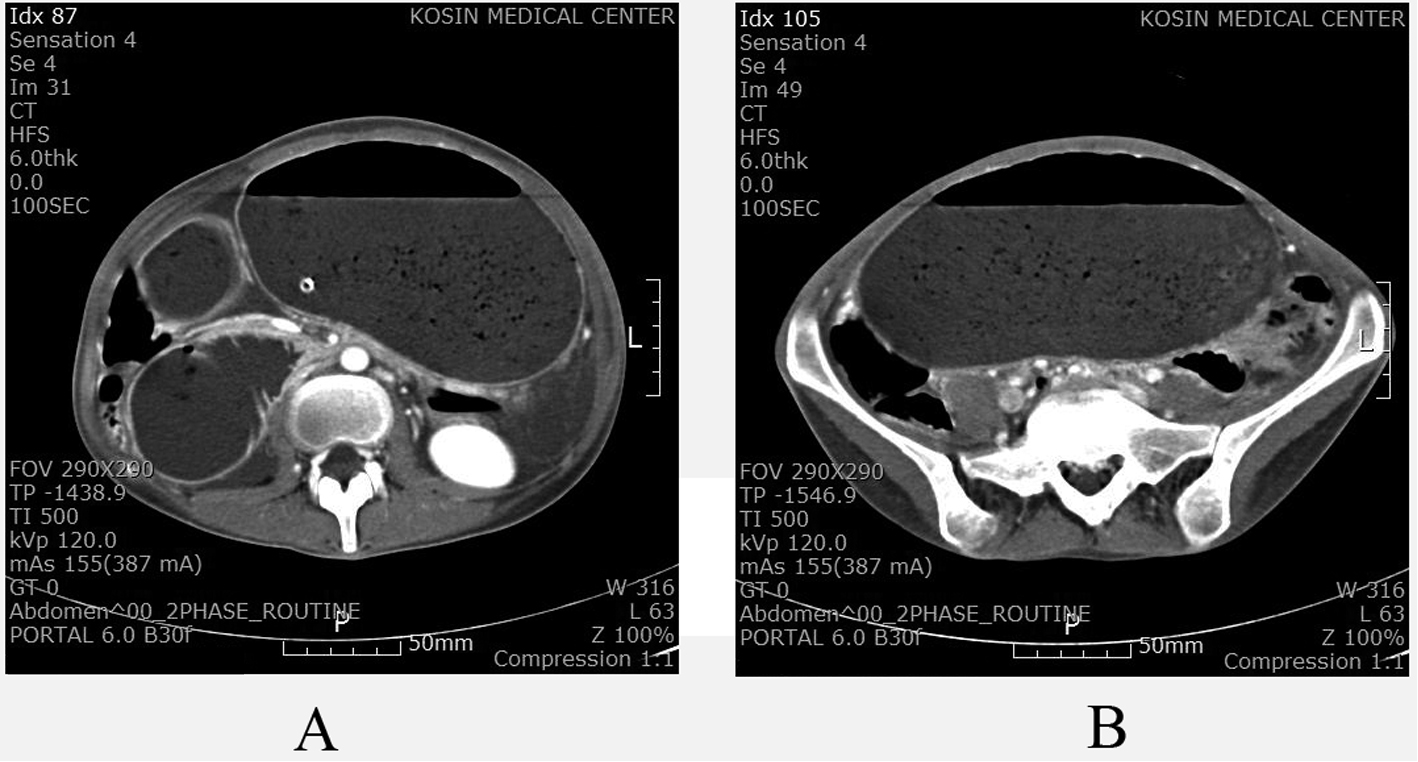

Computed tomography revealed massive stomach dilatation. The stomach occupied the whole abdominal cavity from the epigastric region to the pelvis. The second portion of the duodenum was also dilated. There was no intra-abdominal tumor (Fig. 1). Intravenous fluid replacement was initiated and a nasogastric tube was inserted without difficulty. Only 100 mL of brownish semisolid material was aspirated. On the day after admission, the patient underwent emergent surgery because of aggravating abdominal pain and abdominal fullness. Her vital signs were stable without fever. On laparotomy, the stomach and the second portion of the duodenum were massively dilated. A small perforation surrounded by necrotic change was identified on the fundus of the stomach. The small bowel loops were not dilated. There was no adhesive band, malrotation or tumor. About 2500 mL of food content in the stomach was extracted manually through gastrotomy on the great curvature of the stomach. The perforation site was treated by wedge resection and primary closure. A duodeno-jejunostomy with the side-to-side anastomosis technique was performed for bypass drainage. The patient’s postoperative recovery was uneventful.

Click for large image | Figure 1. CT scan showing massive gastric and duodenal dilatation. The duodenal dilatation was cut off at the origin of the superior mesentery artery (A). The stomach occupied the entire abdominal cavity from the epigastric region to the pelvis (B). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Acute gastric dilatation may occur due to variable etiologies, such as postoperative complication after abdominal surgery, anorexia nervosa and bulimia, psychogenic polyphagia, trauma, electrolyte disturbance, or diabetes mellitus [1-5]. The pathogenesis and pathophysiology of acute gastric dilatation and its complications are not well known. Due to its frequency as a postoperative complication, anesthesia and debilitation have been identified as predisposing factors. Some previous studies demonstrated that superior mesenteric artery syndrome was an underlying cause of increased intragastric pressure, which is a contributing factor of acute gastric dilatation [6, 7]. Other authors suggest that acute gastric dilatation may be a functional entity secondary to regional disease, such as pancreatitis, peptic ulcer, gallbladder stone, or appendicitis [8, 9]. Otherwise, some cases of acute gastric dilatation were reported in patients with eating disorders, such as anorexia nervosa or bulimic binge [2, 6, 8, 10]. A period of starvation in patients with anorexia nervosa may result in atony and muscular atrophy of the stomach. This may also be a predisposing factor for acute gastric dilatation after bulimic attacks [10].

Although the rich collateral blood supply of the stomach may protect it from ischemia, increased intragastric pressure that exceeds the gastric venous pressure, may result in ischemia and infarction. The stomach luminal pressure was exceeding 30 cmH2O results in decreased intramural blood flow of the stomach [11]. Additionally, Revilloid demonstrated in 1885 that the stomachs of cadavers had to be distended by at least 4 liters of fluid to result in perforation [12].

The symptoms of acute gastric dilatation are usually progressive abdominal pain and diffuse abdominal distension [10]. However, pain is sometimes mild in intensity in contrast with the massive distended abdomen. The intensity of abdominal pain may be aggravating after perforation of the stomach. Emesis is also a common symptom of acute gastric dilatation [13]. However, there are reports of patients with acute gastric dilatation who were unable to vomit [4, 14]. It has been suggested that this is caused by the occlusion of the gastroesophageal junction by the distended fundus. In these cases, the patients had intermittent nausea symptoms, but no episodes of vomiting.

For diagnosis of acute gastric dilatation, plain abdominal films may reveal an air-fluid level in a markedly distended stomach without small bowel gas shadows. The most useful diagnostic investigation is an abdominal CT scan that can clearly demonstrate gastric distension [7]. The CT scan may reveal a massively distended stomach reaching the pubic region, displacing organs, and compressing vessels [15]. If perforation is concurrent, pneumoperitoneum may be identified on radiologic investigations.

In some cases of gastric dilatation, recovery may occur with nasogastric decompression without surgery [4, 16]. Partial decompression with nasogastric tube drainage may be helpful for decreasing the intragastric pressure and reducing the risk of necrosis and perforation. After binge-eating, treatment with gastric decompression using a normal sized nasogastric tube is generally unsuccessful [4, 15]. When semisolid material is present in the stomach, even a large tube may be insufficient. If conservative management fails, immediate surgical intervention is mandatory. Surgical options include surgical decompression, bypass duodeno-jejunostomy, partial gastrectomy, total gastrectomy with esophago-jejunostomy, total gastrectomy with cervical esophagostomy and feeding jejunostomy [3-5, 17, 18]. In the case presented here, superior mesenteric syndrome was suspected as a predisposing factor of acute gastric dilatation. The CT scan showed massive dilatation of both the stomach and the second portion of the duodenum. The cutoff of duodenal dilatation was identified at the origin of the superior mesenteric artery. Therefore, surgical decompression with gastrotomy and bypass duodeno-jejunostomy was performed.

Early recognition of gastric infarction is essential for surgical intervention. Gastric necrosis or perforation has been reported as lethal complications of acute gastric dilatation [3, 5, 15, 16, 19]. Progressive abdominal distension, peritonitis, subcutaneous emphysema, and shock may be helpful signs for recognition of gastric necrosis or perforation. In this case, surgical intervention was considered without radiologic investigation for gastric perforation. The patient had suffered progressive abdominal pain and abdominal distension. Emergent laparotomy was performed for surgical gastric decompression and drainage. On laparotomy, perforation on the fundus of the stomach was identified.

Although it is very rare, acute massive gastric dilatation after a binge-eating episode may result in gastric necrosis or perforation, even in patients without a prior history of eating disorder [4]. Careful monitoring for gastric infarction is critical in the management of acute gastric dilatation. When conservative management fails, immediate surgical intervention is mandatory.

| References | ▴Top |

- Cogbill TH, Bintz M, Johnson JA, Strutt PJ. Acute gastric dilatation after trauma. J Trauma. 1987;27(10):1113-1117.

pubmed doi - Nakao A, Isozaki H, Iwagaki H, Kanagawa T, Takakura N, Tanaka N. Gastric perforation caused by a bulimic attack in an anorexia nervosa patient: report of a case. Surg Today. 2000;30(5):435-437.

pubmed doi - Turan M, Sen M, Canbay E, Karadayi K, Yildiz E. Gastric necrosis and perforation caused by acute gastric dilatation: report of a case. Surg Today. 2003;33(4):302-304.

pubmed doi - Lunca S, Rikkers A, Stanescu A. Acute massive gastric dilatation: severe ischemia and gastric necrosis without perforation. Rom J Gastroenterol. 2005;14(3):279-283.

pubmed - Todd SR, Marshall GT, Tyroch AH. Acute gastric dilatation revisited. Am Surg. 2000;66(8):709-710.

pubmed - Pentlow BD, Dent RG. Acute vascular compression of the duodenum in anorexia nervosa. Br J Surg. 1981;68(9):665-666.

pubmed doi - Adson DE, Mitchell JE, Trenkner SW. The superior mesenteric artery syndrome and acute gastric dilatation in eating disorders: a report of two cases and a review of the literature. Int J Eat Disord. 1997;21(2):103-114.

pubmed doi - Backett SA. Acute pancreatitis and gastric dilatation in a patient with anorexia nervosa. Postgrad Med J. 1985;61(711):39-40.

pubmed doi - Gondos B. Duodenal compression defect and the "superior mesenteric artery syndrome" 1. Radiology. 1977;123(3):575-580.

pubmed - Abdu RA, Garritano D, Culver O. Acute gastric necrosis in anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Two case reports. Arch Surg. 1987;122(7):830-832.

pubmed doi - Edlich RF, Borner JW, Kuphal J, Wangensteen OH. Gastric blood flow. I. Its distribution during gastric distention. Am J Surg. 1970;120(1):35-37.

pubmed doi - Kerstein MD, Goldberg B, Panter B, Tilson MD, Spiro H. Gastric infarction. Gastroenterology. 1974;67(6):1238-1239.

pubmed - Chaun H. Massive gastric dilatation of uncertain etiology. Can Med Assoc J. 1969;100(7):346-348.

pubmed - Breslow M, Yates A, Shisslak C. Spontaneous rupture of the stomach: A complication of bulimia. Int J Eat Disord 1986;5:137-142.

- Gyurkovics E, Tihanyi B, Szijarto A, Kaliszky P, Temesi V, Hedvig SA, Kupcsulik P. Fatal outcome from extreme acute gastric dilation after an eating binge. Int J Eat Disord. 2006;39(7):602-605.

pubmed doi - Saul SH, Dekker A, Watson CG. Acute gastric dilatation with infarction and perforation. Report of fatal outcome in patient with anorexia nervosa. Gut. 1981;22(11):978-983.

pubmed doi - Holtkamp K, Mogharrebi R, Hanisch C, Schumpelick V, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Gastric dilatation in a girl with former obesity and atypical anorexia nervosa. Int J Eat Disord. 2002;32(3):372-376.

pubmed doi - Lim JE, Duke GL, Eachempati SR. Superior mesenteric artery syndrome presenting with acute massive gastric dilatation, gastric wall pneumatosis, and portal venous gas. Surgery. 2003;134(5):840-843.

pubmed doi - Koyazounda A, Le Baron JC, Abed N, Daussy D, Lafarie M, Pinsard M. [Gastric necrosis caused by acute gastric dilatation. Total gastrectomy. Recovery]. J Chir (Paris). 1985;122(6-7):403-407.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.