| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 7, July 2022, pages 349-353

A Unique Case of Tri-Valvular Serratia marcescens Infective Endocarditis Complicated by Innumerable Emboli

Walter Evangelista-Abreua, b, Mrhaf Alsammana, b, c , Anteneh Addisua, Nitin Dhaona, Arnaldo Reyesa, Lily Knighta, b, Hamza Alaana, b

aGraduate Medical Education, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando, FL, USA

bInternal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Internal Medicine, Ocala Regional Medical Center, Ocala, FL, USA

cCorresponding Author: Mrhaf Alsamman, Graduate Medical Education, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Central Florida College of Medicine, Orlando, FL 32827, USA

Manuscript submitted May 19, 2022, accepted June 20, 2022, published online July 20, 2022

Short title: Tri-Valvular Serratia marcescens IE

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3954

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Serratia marcescens (S. marcescens) is a gram negative bacterium rarely associated with cases of infective endocarditis (IE). Involvement of three cardiac valves, as evidenced by echocardiography, is uncommon as well. S. marcescens IE and tri-valvular endocarditis have been rarely described in literature. We report a unique case of S. marcescens tri-valvular IE in a 42-year-old female with sudden altered mental status and no underlying structural heart disease complicated by embolic infarcts in both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, and a sub-arachnoid hemorrhage. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of tri-valvular S. marcescens IE. We believe this report will add to the growing literature of rare bacterial IE and considering this in the differential in the right clinical scenario.

Keywords: Infective endocarditis; Serratia marcescens; Bacteremia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Infective endocarditis (IE) is an infection of the endocardium typically resulting from a bacterial infection. Despite an increasing arsenal of antibiotic medication and improved surgical intervention techniques, endocarditis remains a severely morbid condition with a 30-day death rate of 20%. Chronic renal disease, cancer, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), and advanced age are all linked to an increased risk of endocarditis. Contact with the healthcare system itself might be a risk factor. One endocarditis cohort study revealed that 25% of afflicted individuals had recently been exposed to the healthcare system [1]. Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) is currently the most common organism associated with IE in the industrialized world. Other typical causal microorganisms include Viridans streptococci, Streptococcus bovis, HACEK (Haemophilus, Aggregatibacter, Cardiobacterium, Eikenella, and Kingella) group, or community acquired Enterococci. Gram negative bacilli, such as Serratia marcescens (S. marcescens), rarely cause IE [2, 3]. First identified in 1819 by Bartolemeo Bizio, S. marcescens is a facultative anaerobic gram negative bacillus. Serratia species are Enterobacteriaceae found in human intestinal flora. However, as Serratia are ubiquitous organisms in the environment (including in healthcare institutions), infections are most commonly associated with exogenous sources [4]. The nails of health care workers, medical equipment, and even sinks have been associated with outbreaks of Serratia infections [5]. S. marcescens is the most frequent (90%) Serratia spp. recovered in clinical practice [2]. Nevertheless, it is typically associated with urinary tract infections and rarely causes IE [3]. In IE, it has predilection for left sided valves [6, 7]. To our knowledge, this is the first reported case of tri-valvular S. marcescens IE. We believe this report will provide with information for a better understanding of this presentation.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 42-year-old female was brought in due to sudden onset altered mental status. Per family, patient was previously healthy, presented low grade fevers for 5 days and had a sudden deterioration in mental status on the day of admission. The patient has history of intravenous drug use (IVDU) but did not use any IV drugs in the past 12 months. Of notice, patient had extraction of all maxillary teeth 5 months prior and a mandibular dental infection 3 months before presentation treated with oral amoxicillin. Upon presentation, the patient’s temperature was 36.7 °C, heart rate was 98 beats/min, respiratory rate was 17 breaths/min, blood pressure was 131/66 mm Hg, oxygen saturation of 99% on room air. The patient denied fevers, chills, chest pain, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, skin lesions, numbness, tingling, and weakness of the lower extremities. On physical examination, she had a prominent holosystolic murmur at the apex. She also presented a petechial rash scattered on the abdomen, palms, and soles of the feet. Her neurological exam was remarkable for an encephalopathy, facial droop, and slurred speech. She was admitted to the intensive care unit for closer monitoring. She was then started on empiric antibiotic treatment with vancomycin and meropenem. On day 1 of admission, the patient became unresponsive to voice, minimally responsive to pain, presented left hemi-neglect and right gaze deviation. Her Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) was 6. Thus, she was intubated for airway protection.

Diagnosis

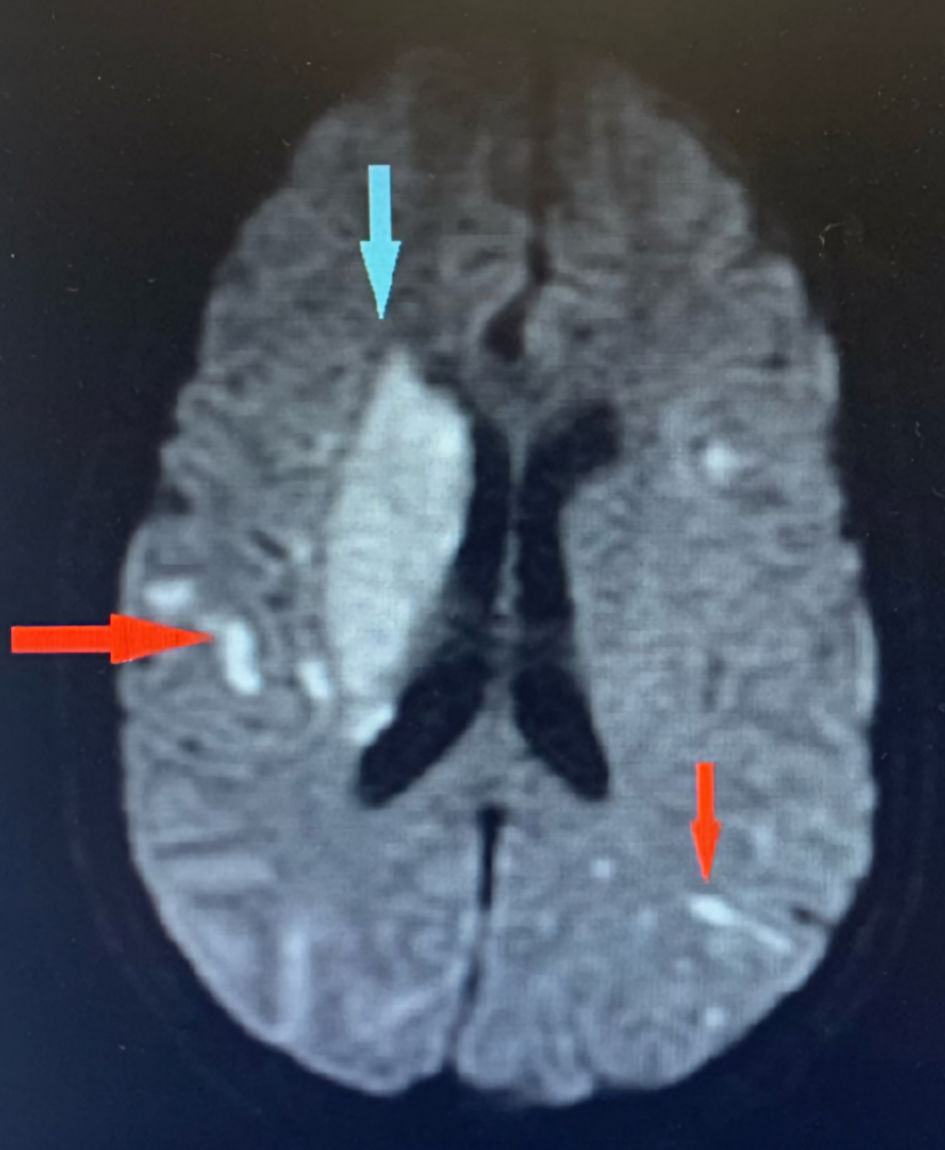

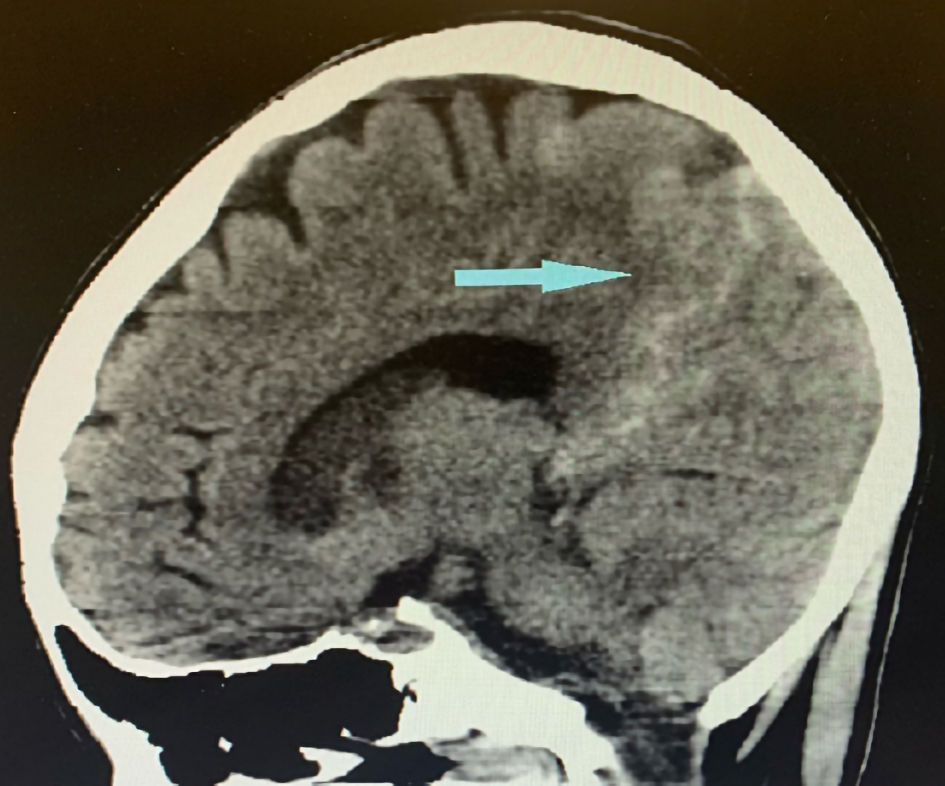

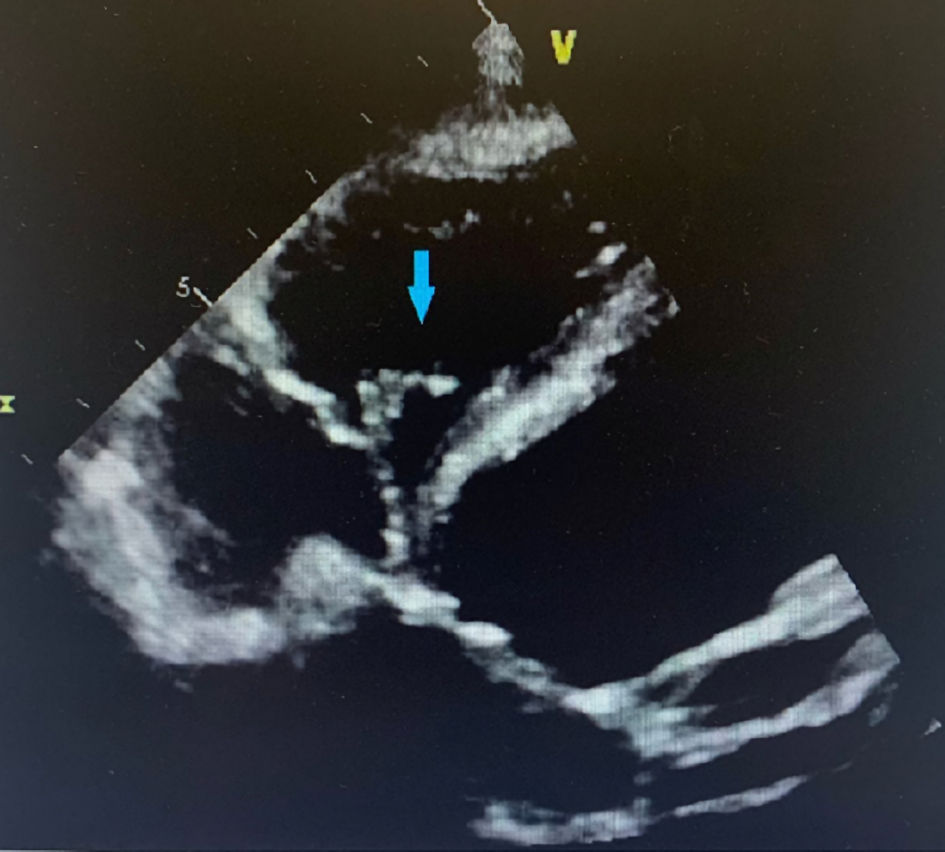

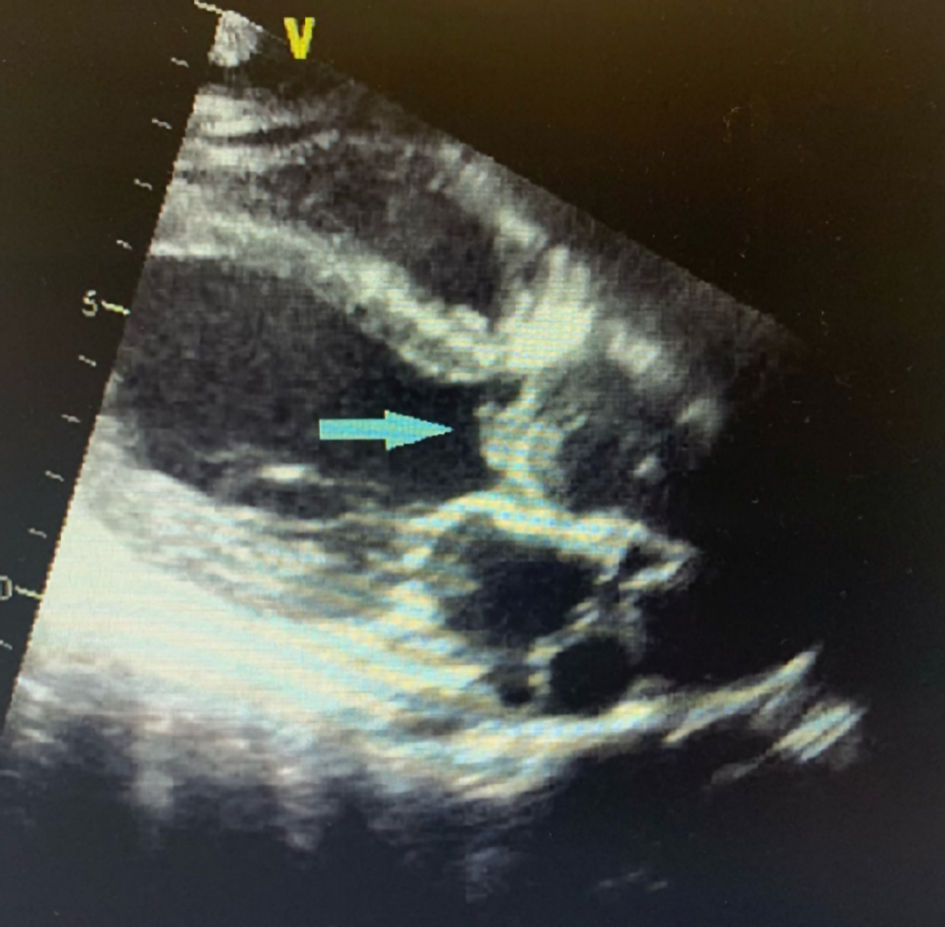

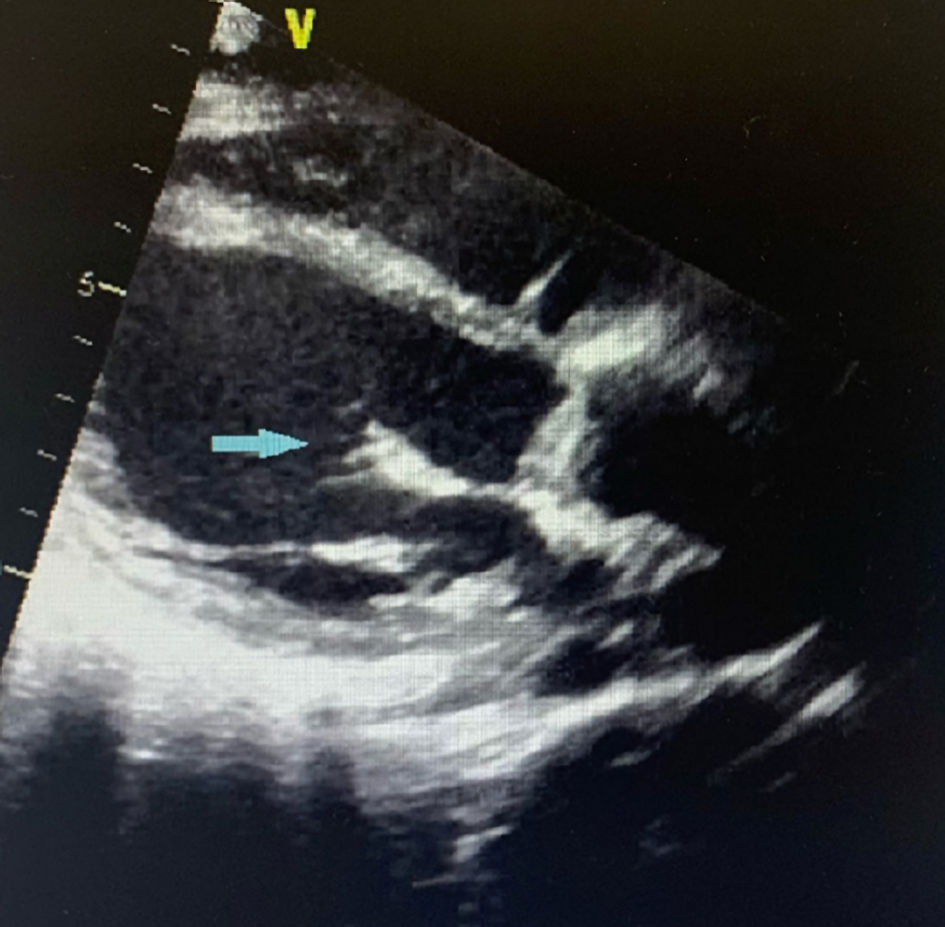

Laboratory results were remarkable for leukocytosis of 24.7 × 109/L with 87.6% neutrophils and a platelet count of 17 × 109/L. Liver and kidney functions were within normal. Patient declined a HIV test. Imaging findings showed innumerable acute to subacute embolic infarcts in both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres, the largest involving the right lentiform nucleus and corona radiata. Further imaging findings include a proximal right internal carotid artery T-shaped acute thrombus, an occlusion of the right middle cerebral artery, and subarachnoid hemorrhage in the right parietal region and around the posterior aspect of the midbrain (Figs. 1, 2). A transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) showed echo densities on the tricuspid, aortic, and mitral valves (Figs. 3-5), which were consistent with valvular vegetations. As there was clear evidence of vegetations on multiple valves, a transesophageal echocardiogram (TEE) was not conducted. Blood culture grew S. marcescens in two bottles.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Brain MRI showing innumerable acute to subacute embolic infarcts in both cerebral hemispheres (red arrows). The largest infarct involves the right lentiform nucleus and corona radiate (blue arrow). MRI: magnetic resonance imaging. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Sagittal image of brain CT showing subarachnoid hemorrhage (blue arrow). CT: computed tomography. |

Click for large image | Figure 3. Four chamber view of TTE showing tricuspid valve vegetation (blue arrow). TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram. |

Click for large image | Figure 4. Parasternal long axis view of TTE showing aortic valve vegetation (blue arrow). TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram. |

Click for large image | Figure 5. Parasternal long axis view of TTE showing mitral valve vegetation (blue arrow). TTE: transthoracic echocardiogram. |

Treatment

The S. marcescens isolate was pansensitive susceptible to ceftriaxone, cefepime, ceftazidime, meropenem, gentamicin, tobramycin, amikacin, ciprofloxacin, and levofloxacin. On day 3, antibiotic was changed to cefepime according to the susceptibility results. Cardiothoracic surgery consulted but patient was a poor candidate for surgery due to deterioration in neurological status.

Follow-up and outcomes

Over the next days, the neurological status of the patient continued to deteriorate. By day 6, she presented no cough or gag reflex, pupils were fixed and mid-dilated. The patient’s family decided to withdraw care on day 6 of admission due to patient’s multiple co-morbidities with poor prognosis and expected substantial deterioration in quality of life. Patient was discharged to hospice care.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

This was an unusual presentation of IE with severe complications due to triple valves involvement, and innumerable emboli leading to severe neurological sequelae. The International Collaboration on Endocarditis (ICE) prospective multinational cohort that included 61 hospitals in 28 countries reported only four cases (0.14% of the total) of S. marcescens IE out of 2,761 cases hospitalized patients with definite endocarditis [8]. Likewise, IE involving three cardiac valves is uncommon. There are limited studies that include information on prognosis, prevalence, and treatment [9, 10].

In a literature review of 232 patients with IE involving the right heart conducted from January 1, 2008 to April 30, 2013, Yuan et al identified five cases (2.2%) involved three valves [11]. As right sided IE accounts for 5-10% of IE cases [12], we can conservatively estimate triple valvular IE to account for 0.22% of IE cases. Multiple valve IE has been typically associated with S. aureus and Streptococcus viridans (S. viridans) [10]. Our patient presented vegetations on three heart valves. The predilection of Serratia for left sided valves is not yet fully understood. The left sided involvement commonly results in systemic embolization, while the tricuspid involvement adds the risk of pulmonary emboli. In our patient, innumerable infarcted areas in both cerebral and cerebellar hemispheres were noted, significantly worsening the patient prognosis.

Reports published in 1976 and 1980 linked Serratia endocarditis to a history of IVDU (89% of cases). However, case reports from 1980 to 2016 attributed only two of 20 Serratia IE cases to IVDU [13]. Conversely, a recent retrospective cohort study that included 103 adult patients admitted to four hospitals in Ohio from January 2014 to December 2018 concluded that 42 (43%) cases of Serratia bacteremia could be attributed to IVDU. The study hypothesized that lack of sterile technique, reuse of needles and utilization of tap water could be the culprit for the resurgence in this population. Seven of the forty-two patients with Serratia bacteremia in the cohort developed IE [13].

Our patient was diagnosed with IE as she met the modified Duke criteria of one major criterion (new valvular regurgitation) and four minor criteria (predisposing factor of IVDU, fever, vascular phenomena, and microbiologic evidence). As Serratia is not a typical oropharyngeal organism, we consider that the main predisposing risk factor and likely source of the infection is a history of IVDU.

However, the sensitivity of these modified Duke criteria is restricted, particularly at an early stage of the illness, in the presence of a negative blood culture, and in the presence of a prosthetic valve or pacemaker/defibrillator leads. When blood cultures are negative, new diagnostic methods are evolving to enhance pathogen identification and to indicate endocardial involvement or vascular problems when echocardiography is negative or uncertain. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR), immunohistochemistry, systematic serologies, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and molecular imaging are all potential technologies that might be included in future diagnostic classifications [14].

Following endothelial damage, the release of inflammatory cytokines and tissue factors, together with fibronectin production, results in the creation of a platelet-fibrin thrombus, which facilitates bacterial adhesion [15].

Microbial elimination by antimicrobial agents alone or in conjunction with surgery is required for the treatment of patients with IE. Antibiotic concentrations in the serum should be high to ensure medication penetration into vegetation. To eradicate latent bacteria grouped in infected foci, long-term therapy (4 - 6 weeks) is required. The choice of antibiotic is dependent on the drug’s minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) for the infection. Drug therapy for prosthetic valve endocarditis is prolonged (at least 6 weeks) than for native valve endocarditis (2 - 6 weeks), but it is qualitatively comparable, with the exception of staphylococcal prosthetic valve endocarditis (PVE), which should always include rifampin if the strain is sensitive to it. Inadequate antibiotic delivery, the existence of a surgically removed focus, or antibiotic resistance can all lead to treatment failure [16].

Conclusions

This case reports a previously healthy 42-year-old female with history of IVDU, who developed tri-valvular S. marcescens endocarditis with septic embolization to the brain causing numerous infarcts and a sub-arachnoid hemorrhage. S. marcescens is an uncommon organism to cause endocarditis. While mainstay treatment remains IV antibiotics, surgery is sometimes considered. Most data available is derived from case reports, we believe further studies will help us understand better the aggressive course this organism can present.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they do not have a financial relationship with any commercial entity that has an interest in the subject of this manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained per care guidelines.

Author Contributions

WEA contributed to the writing of the discussion section. MA contributed to the introduction section and figures. AA contributed to the abstract section. ND contributed to the final review of the manuscript. AR contributed to the conclusion section. LK contributed to the case presentation. AH contributed to the final review and editing of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Disclaimer

HCA Healthcare and/or an HCA Healthcare associated company supported this research (in whole or in part). The opinions stated in this article are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect HCA Healthcare or any of its associated companies’ official positions.

| References | ▴Top |

- Vincent LL, Otto CM. Infective endocarditis: update on epidemiology, outcomes, and management. Curr Cardiol Rep. 2018;20(10):86.

doi pubmed - Russo TA, Johnson JR. Diseases caused by gram-negative enteric bacilli. In: Loscalzo J, Fauci A, Kasper D, Hauser S, Longo D, Jameson J, eds. Harrison's principles of internal medicine, 21e. McGraw Hill; 2021.

- Enteric gram-negative rods (Enterobacteriaceae). In: Riedel S, Hobden JA, Miller S, Morse SA, Mietzner TA, Detrick B, Mitchell TG, et al. Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg's medical microbiology, 28e. McGraw Hill; 2019.

- Gram-negative rods related to the enteric tract. In: Levinson W, Chin-Hong P, Joyce EA, Nussbaum J, Schwartz B. eds. Review of medical microbiology & immunology: a guide to clinical infectious diseases, 17e. McGraw Hill; 2022.

- Khanna A, Khanna M, Aggarwal A. Serratia marcescens- a rare opportunistic nosocomial pathogen and measures to limit its spread in hospitalized patients. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(2):243-246.

doi pubmed - Yeung HM, Chavarria B, Shahsavari D. A complicated case of serratia marcescens infective endocarditis in the era of the current opioid epidemic. Case Rep Infect Dis. 2018;2018:5903589.

doi pubmed - Murdoch DR, Corey GR, Hoen B, Miro JM, Fowler VG, Jr., Bayer AS, Karchmer AW, et al. Clinical presentation, etiology, and outcome of infective endocarditis in the 21st century: the International Collaboration on Endocarditis-Prospective Cohort Study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(5):463-473.

doi pubmed - Morpeth S, Murdoch D, Cabell CH, Karchmer AW, Pappas P, Levine D, Nacinovich F, et al. Non-HACEK gram-negative bacillus endocarditis. Ann Intern Med. 2007;147(12):829-835.

doi pubmed - Bortolotti U. Triple valve endocarditis: the case for multiple valve replacement. Gen Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2021;69(7):1163.

doi pubmed - Lopez J, Revilla A, Vilacosta I, Sevilla T, Garcia H, Gomez I, Pozo E, et al. Multiple-valve infective endocarditis: clinical, microbiologic, echocardiographic, and prognostic profile. Medicine (Baltimore). 2011;90(4):231-236.

doi pubmed - Yuan SM. Right-sided infective endocarditis: recent epidemiologic changes. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7(1):199-218.

- Shmueli H, Thomas F, Flint N, Setia G, Janjic A, Siegel RJ. Right-sided infective endocarditis 2020: challenges and updates in diagnosis and treatment. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(15):e017293.

doi pubmed - McCann T, Elabd H, Blatt SP, Brandt DM. Intravenous Drug Use: a Significant Risk Factor for Serratia Bacteremia. Ther Adv Infect Dis. 2022;9:20499361221078116.

doi pubmed - Thuny F, Grisoli D, Cautela J, Riberi A, Raoult D, Habib G. Infective endocarditis: prevention, diagnosis, and management. Can J Cardiol. 2014;30(9):1046-1057.

doi pubmed - Cahill TJ, Prendergast BD. Infective endocarditis. Lancet. 2016;387(10021):882-893.

doi - Que YA, Moreillon P. Infective endocarditis. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2011;8(6):322-336.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.