| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 7, July 2022, pages 322-329

Acute Interstitial Nephritis Induced by Clozapine

Praveena Vantipallia, i, Sasmit Royb, i, Narayana M. Koduric, Venu Madhav Konalad, Amarinder Singh Garchae, Srikanth Kunaparajuf, Raul Ayalag, Samanvitha Sai Yarramh, Sreedhar Adapae

aDepartment of Family Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA

cDepartment of Psychiatry, Great Plains Health, North Platte, NE, USA

dDepartment of Internal Medicine, Precision Cancer Center, Ashland, KY, USA

eDepartment of Internal Medicine, Adventist Health, Hanford, CA, USA

fRichmond Nephrology Associates, Richmond, VA, USA

gDepartment of Family Medicine, Adventist Health, Hanford, CA, USA

hGeneral Medicine, The University of New England Joint Medical Program, Armidale, New South Wales, Australia

iCorresponding Author: Sasmit Roy, Department of Internal Medicine, University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, USA; Praveena Vantipalli, Department of Family Medicine, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198, USA

Manuscript submitted March 23, 2022, accepted April 27, 2022, published online June 16, 2022

Short title: Clozapine-Induced Acute Interstitial Nephritis

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3934

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) classically presents as acute kidney injury most often induced by offending drugs. Less frequently it is secondary to infections, autoimmune disorders, or idiopathic conditions. Development of drug-related AIN is not dose dependent and a recurrence can occur with re-exposure to the drug. We present a 50-year-old male with treatment resistant schizoaffective disorder who developed clozapine-induced AIN, confirmed with kidney biopsy within 2 months of taking this medication. His kidney function improved with removal of the drug and treatment with steroids. However, his kidney function was again significantly impaired when rechallenged with even a lower dose of clozapine a year later. Kidney function returned to baseline after stopping clozapine. Monitoring of kidney function during clozapine therapy is essential to therapy. Prompt diagnosis is imperative as discontinuation of offending agent can prevent acute kidney injury.

Keywords: Acute interstitial nephritis; Clozapine; Refractory schizophrenia; Acute kidney injury; Drug reactions; Kidney biopsy; Schizophrenia

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Clozapine has superior efficacy in treating refractory schizophrenia in comparison to other antipsychotic medications [1]. Common side effects of clozapine include weight gain, constipation, oversedation, orthostatic hypotension, and sialorrhea [2]. Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is a very rare side effect of clozapine and has been reported rarely in the literature. It is often unrecognized in the early stages because of its asymptomatic nature but it can be life-threatening. We describe a case of AIN caused by clozapine that was confirmed by the kidney biopsy and reoccurrence of acute kidney injury (AKI) in 1 year later with rechallenge.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 50-year-old male with a known history of schizoaffective disorder and bipolar disorder was admitted to the inpatient psychiatry unit with uncontrolled psychosis. The patient had grandiose delusions, referential delusions, thought broadcasting, and delusional perception. The psychosis has been getting worse 4 - 6 weeks before admission despite being compliant with psychotropic medications. The patient was diagnosed with schizoaffective and bipolar disorder at the age of 30. The patient has been treated before with both typical, atypical antipsychotic agents and mood-stabilizing agents which include chlorpromazine, fluphenazine, haloperidol, perphenazine, aripiprazole, risperidone, paliperidone, olanzapine, valproic acid, and lithium. Some of these agents have been given in long-acting injectable routes. Despite medication trials, intensive community support, assisted living facility placements, the patient’s illness remained resistant to treatment which led to frequent and prolonged hospitalizations.

His past medical history is also significant for essential hypertension. His medications at the time of admission included paliperidone 12 mg daily, sodium valproate 500 mg in the morning, 1,000 mg at bedtime, lithium carbonate 300 mg twice daily, benztropine 0.5 mg twice daily, and amlodipine 10 mg daily. The patient was staying at the assisted living facility before admission. The patient had no prior history of smoking, alcohol use, or recreational drug use. The patient was divorced and had no family history of psychiatric illness.

The vitals on the admission were a temperature of 36.9 °C, pulse rate of 80 beats per minute (bpm), blood pressure of 135/80 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 18 breaths per minute. The physical examination was suggesting an anxious and confused person, but the rest of the physical examination was unremarkable. The psychiatric evaluation revealed that the speech was rapid, with intact language functioning, euphoric with manic affect. The thought process was significant for loose associations and paranoia.

Diagnosis

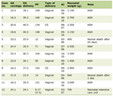

The labs on the first admission are shown in Table 1. The patient was started on clozapine 25 mg daily and the dose was up titrated to 300 mg daily gradually over 2 weeks. Lithium was continued at the same dose and the rest of the anti-psychotics were stopped. The patient’s psychosis improved significantly, and he was discharged to assisted living. The patient was readmitted back to the inpatient psychiatry unit in 5 days with fatigue, fever, and sweating. The vitals revealed temperature 38.6 °C, pulse rate of 110 bpm, blood pressure 140/90 mm Hg, respiratory rate of 24 breaths per minute. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing individual, while the rest of the systemic examination was not significant. No rigidity or fluctuating consciousness was noted.

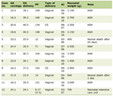

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Values During Hospitalizations |

The labs on the second visit are depicted in Table 1. Notable serum finding was elevated serum clozapine level of 506 ng/mL. The patient was symptomatically treated for fever and was discharged on a decreased dose of clozapine 150 mg daily. Lithium was continued at the same dose.

The patient was readmitted again to the medical floor 6 days later with generalized weakness, fever, chills, and sweating. Vitals revealed temperature 38.3 °C, pulse rate of 115 bpm, blood pressure 163/98 mm Hg, respiratory rate 24 breaths per minute. Physical examination revealed an ill-appearing male and the rest of the examination was unremarkable.

The labs on the third admission are shown in Table 1. The kidney function labs continued to worsen despite intravenous fluids over the next 2 days, with blood urea nitrogen 23 mg/dL and creatinine 4.6 mg/dL. Ultrasound of the kidneys revealed right kidney measuring 9.3 cm in length, left kidney 9.7 cm in length, no stones, no masses, no hydronephrosis, and no cysts. The urine protein creatinine ratio was 0.8 mg/g and urine eosinophils were positive. Nephrology was consulted who recommended discontinuation of clozapine, initiation of oral steroids, and performing kidney biopsy.

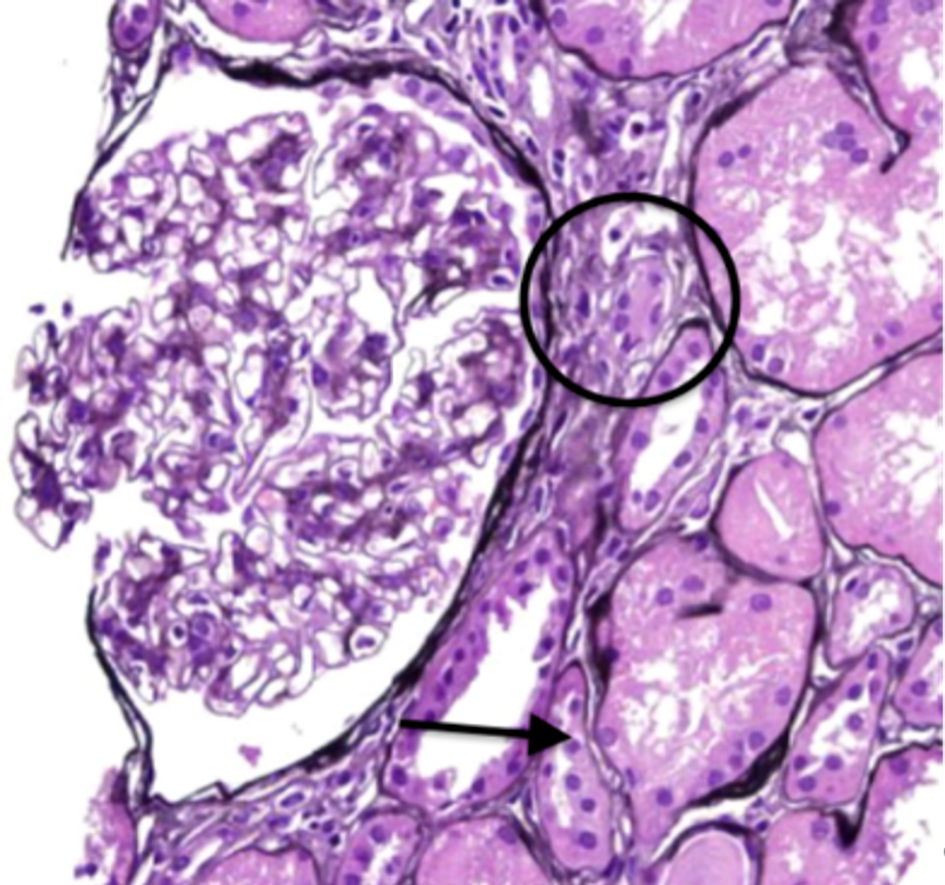

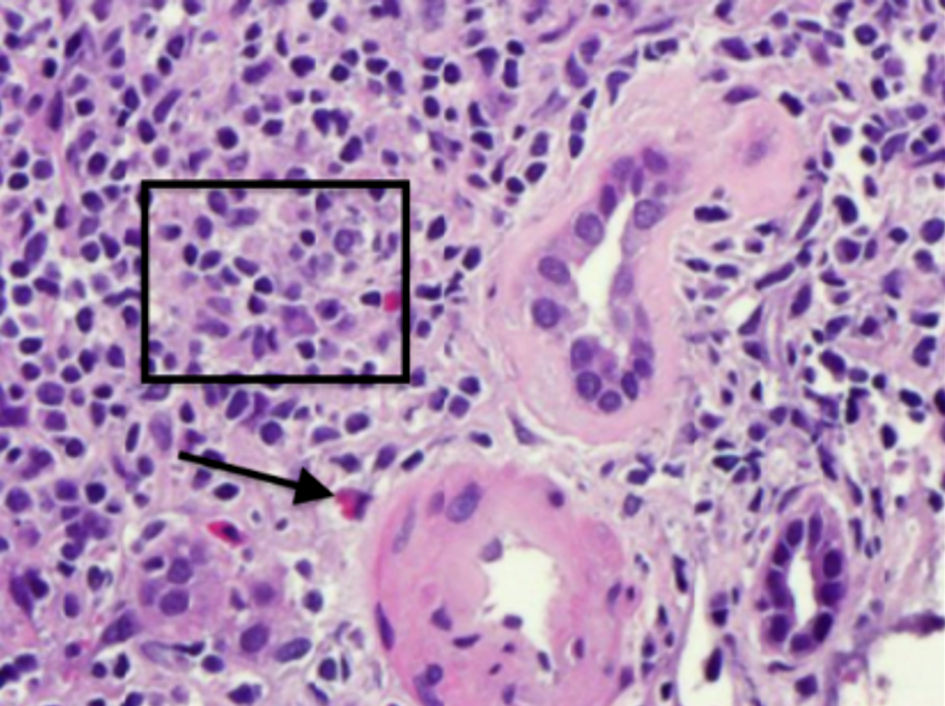

Serologies for glomerulonephritis revealed normal complements, negative anti-nuclear antibody, negative anti-neutrophilic cytoplasmic antibody, negative anti-glomerular basement membrane antibody, negative hepatitis B and C virus studies, and negative human immunodeficiency virus serologies. Complete blood count did not reveal any eosinophilia. The kidney biopsy revealed 11 globally sclerotic glomeruli, no hypercellularity, no necrosis, and no crescents. Moderate interstitial fibrosis (50%) with associated tubular atrophy and moderate mononuclear interstitial inflammation with plasma cells and eosinophils (Figs. 1, 2). Moderate arteriosclerosis was present. No immune type or electron-dense deposits were identified on immunofluorescent and electron microscopy confirming the diagnosis of acute tubulointerstitial nephritis.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Periodic acid-Schiff staining displaying moderate mononuclear inflammation (circle) with associated tubular atrophy (arrow). |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Hematoxylin and eosin staining demonstrating moderate mononuclear interstitial inflammation (square) with plasma cells and eosinophil (arrow). |

Treatment

The serum creatinine plateaued around 4.0 - 4.1 mg/dL over the next few days. The patient was treated with 6 weeks tapering course of prednisone. The serum creatinine on discharge was 3.7 mg/dL. The serum creatinine returned to a baseline of 1.2 mg/dL at 2 months. The patient was treated with olanzapine, lorazepam, valproic acid, and paliperidone over the next year at assisted living without complete remission of symptoms.

Follow-up and outcomes

The patient was readmitted to the inpatient psychiatric unit a year later with uncontrolled psychosis and worsening aggression. The patient had significant grandiose, religious, paranoid delusions. At that point, he was acting on his delusion which led to the physical injury of his partner, which precipitated inpatient psychiatric hospitalization. Considering treatment resistance and worsening aggression, the patient was rechallenged on treatment with clozapine 25 mg, and the dose was gradually up titrated to 75 mg daily over 3 days. The patient developed a fever with chills and rigors. Vitals revealed temperature 38.2 °C, pulse rate of 104 bpm, blood pressure 145/89 mm Hg, respiratory rate 20 breaths per minute. Physical examination was unremarkable. The labs revealed worsening serum creatinine from 1.31 mg/dL on admission to 1.91 mg/dL. Clozapine was stopped with the resolution of fever. Kidney function improved back to baseline in 2 weeks.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Clozapine, a tricyclic dibenzodiazepine is a second-generation atypical antipsychotic [2]. It exerts its anti-psychotic effects by antagonizing serotonin and dopamine receptors [2]. Clozapine is particularly used in treatment-resistant schizophrenia [3]. Treatment resistance is defined as failure to achieve remission despite using two or more antipsychotics [3]. Clozapine has fewer extrapyramidal side effects and less tardive dyskinesias compared to typical antipsychotics which makes it more appealing [2]. It is also effective in treating schizoaffective disorders and causes minimal changes in prolactin levels [2].

Despite the efficacy of clozapine, the use is limited by the side effect profile. The common side effects are fever, orthostasis, sialorrhea, oversedation, and more serious agranulocytosis [2]. Myocarditis, hepatitis, pancreatitis, vasculitis, pulmonary syndrome, and AKI due to interstitial nephritis are rarely encountered side effects [2]. Considering these potentially fatal side effects the use of clozapine is limited and should be offered only after two antipsychotics fail to achieve remission [3].

AIN classically presents as AKI most often induced by offending drugs. Less frequently AIN is secondary to infections, autoimmune disorders, and idiopathic causes [4]. The classic features of AIN include fever, rash, and eosinophilia, which may not be present in all cases. A high index of suspicion is needed in diagnosing AIN as a cause of AKI. AIN approximates 15-20% of AKI cases and contributes to 2.8% diagnosis of all the kidney biopsies [4]. The diagnosis is based on the clinical course and investigations. Particular attention should be paid to the history of infections, autoimmune diseases, and drug exposure history should be thoroughly sought. The offending agents should be promptly identified and stopped. The common drug classes which are known to cause AIN are antibiotics and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). Tubular inflammation with cellular infiltrates and interstitial edema is the distinctive feature noted on the kidney biopsy and establishes the diagnosis.

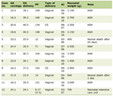

New onset proteinuria, hematuria, and AKI after initiating treatment with clozapine and improvement in the kidney function parameters after cessation of treatment establish the casual relationship. To the best of our knowledge, clozapine-induced AIN has been reported only 16 times in the literature review [5-20]. The clinical characteristics, investigations, kidney injury outcomes have been summarized in Tables 2 and 3.

Click to view | Table 2. Clinical Characteristics of AIN From Clozapine |

Click to view | Table 3. Kidney Function Parameters and Management of AIN From Clozapine |

AIN caused by clozapine is a drug hypersensitivity reaction, and rapid onset of AKI after rechallenging with clozapine supports that immunological memory plays a role in the pathogenesis [6]. Antigen reactive T cells play a fundamental role in dysregulating immunological response and may be contributing to AIN as supported by human and animal studies [4]. Foreign antigens are implicated in causing idiosyncratic hypersensitivity reactions. In drug-induced AIN, the idiosyncratic nature is distinctly indicated by the occurrence of reaction in a minority of individuals, non-dose relation, systemic hypersensitivity presentation, and recurrence with re-exposure [4]. The simultaneous incidence of interstitial nephritis and cardiomyopathy and the presence of eosinophils support the possibility of immunoglobulin (Ig)E-mediated hypersensitivity reaction [15].

Elevated plasma levels of clozapine have been reported in the literature before once in clozapine-induced AIN, once in clozapine-induced pancreatitis, and twice in clozapine-induced hepatitis [6, 21]. The dosing of clozapine was around 300 mg in all the cases reported with elevated plasma levels [6]. Multitude factors play a role in the elevation of the plasma levels of clozapine including elevation of alpha1 acid glycoprotein which is an acute-phase protein and most of the clozapine bind to it [6]. Downregulation of the cytochrome P450 system by cytokines may also play a role [6]. Plasma clozapine level of 250 - 350 ng/mL is a reasonable target for a patient with schizophrenia. For those who have refractory symptoms, it is reasonable to target clozapine levels higher than 350 ng/mL despite limited evidence [22].

The occurrence of AIN with clozapine in the cases reported was approximately within 2 weeks in a majority but was delayed up to 1 - 3 months in a few cases as summarized in Tables 2 and 3. Kidney biopsy was done in seven cases which confirmed the diagnosis [6, 9, 10, 12, 17, 18, 20]. Clozapine rechallenge was done in three cases [5, 6, 14], which resulted in the occurrence of AKI within a few days or with few doses. The dosage of clozapine ranged from 25 mg to 700 mg in the cases where AKI occurred [6]. Proteinuria quantification was reported in only three cases and was in the sub nephrotic range [9, 10, 19]. A few patients had exposure to the antibiotics because of suspicion of infection, which may have perpetuated the AIN caused by clozapine, although there is no conclusive evidence [13]. Few patients never regained the baseline kidney function after developing AKI with clozapine [6, 7, 12, 15, 16]. About half of the patients in the cases reported were treated with steroids and only three patients needed dialysis which was outlined in Table 3. The factors to consider for favorable kidney health prognosis are baseline kidney function, kidney failure duration, kidney function trend after stopping the drug, and the length of exposure to the drug [6] (Table 3).

The clinical history of drug exposure, symptoms like fever and rash, and lab findings like eosinophilia, eosinophiluria, hematuria, proteinuria, sterile pyuria, and white blood cell (WBC) casts should raise the suspicion of AIN. Stopping the offending drug and resolution of clinical findings supports the diagnosis. Kidney biopsy is the gold standard test in establishing the diagnosis of interstitial nephritis, which is not done in all cases. Biopsy revealing the presence of eosinophils should point towards drug-induced AIN, while infection reveals the presence of neutrophils [9].

The mainstay in the treatment of interstitial nephritis is to stop the offending drug. Corticosteroids are used to hasten the recovery and prevent progression to chronic kidney disease (CKD). The electrolytes, acid-base status, and fluid balance should be carefully monitored, and provision of renal replacement therapy is warranted when needed. The patients should be followed by the nephrologist for any evidence of residual CKD and managed appropriately.

The Naranjo score is used to identify AIN as a possibility of drug reaction [23]. The causative drug is identified by the highest score accumulated. The Naranjo score calculated in our patient suggested that the interstitial nephritis is most likely caused by clozapine.

Lastly, we want to emphasize that although we did kidney biopsy in our case, biopsy is not always necessary to confirm AIN if the helpful positive findings like urine eosinophilia or exposure to known offending drugs are present in history and physical examination. However, as clozapine is very seldom known to cause AIN and it was the only lifesaving drug in this case of resistant psychosis, kidney biopsy was performed as a confirmative means before any decision was made to stop this drug.

Learning points

This case report highlights the rare but serious side effect of clozapine causing AIN and the importance of prompt recognition and treatment. In addition to cell counts, it is pivotal to establish the baseline kidney function before treatment and close monitoring is warranted during treatment. Patients with drug reactions from the previous trial of clozapine should only be rechallenged if necessary and should be done with due caution. Early nephrology consultation should be obtained if there is evidence of kidney function impairment. Discontinuation of the offending agent and steroid therapy can reduce further kidney injury and can be lifesaving.

Acknowledgments

None to declare.

Financial Disclosure

None to disclose.

Conflict of Interest

The authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Informed Consent

The patient consented for publication of this study.

Author Contributions

Each author has been individually involved in and has made substantial contributions to conceptions and designs, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting, and editing the manuscript. Praveena Vantipalli contributed to the acquisition of data, drafting, and editing of the manuscript. Sasmit Roy contributed to the designs, analysis, interpretation of data, and editing of the manuscript and with final submission. Narayana M. Koduri contributed to the designs, interpretation of data, drafting, and editing of the manuscript. Venu Madhav Konala contributed to the drafting and interpretation of data. Amarinder Singh Garcha contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. Srikanth Kunaparaju contributed to the drafting and editing of the manuscript. Raul Ayala contributed to the designs, analysis, and editing of the manuscript. Samanvitha Sai Yarram contributed to the analysis and editing of the manuscript. Sreedhar Adapa contributed to the designs, acquisition of data, analysis, interpretation of data, drafting, and editing of the manuscript.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Siskind D, McCartney L, Goldschlager R, Kisely S. Clozapine v. first- and second-generation antipsychotics in treatment-refractory schizophrenia: systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Psychiatry. 2016;209(5):385-392.

doi pubmed - De Fazio P, Gaetano R, Caroleo M, Cerminara G, Maida F, Bruno A, Muscatello MR, et al. Rare and very rare adverse effects of clozapine. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2015;11:1995-2003.

doi pubmed - Keepers GA, Fochtmann LJ, Anzia JM, Benjamin S, Lyness JM, Mojtabai R, Servis M, et al. The American Psychiatric Association Practice Guideline for the treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Am J Psychiatry. 2020;177(9):868-872.

doi pubmed - Raghavan R, Eknoyan G. Acute interstitial nephritis - a reappraisal and update. Clin Nephrol. 2014;82(3):149-162.

doi pubmed - Bassetti N, Civardi SC, Parente S, et al. Clozapine-induced acute interstitial nephritis: a case report. Biomedical Journal of Scientific & Technical Research. 2021;38(5):30744-30746.

doi - McLoughlin C, Cooney C, Mullaney R. Clozapine-induced interstitial nephritis in a patient with schizoaffective disorder in the forensic setting: a case report and review of the literature. Ir J Psychol Med. 2022;39(1):106-111.

doi pubmed - Davis EAK, Kelly DL. Clozapine-associated renal failure: A case report and literature review. Ment Health Clin. 2019;9(3):124-127.

doi pubmed - Caetano D, Sloss G, Piatkov I. Clozapine-induced acute renal failure and cytochrome P450 genotype. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2016;50(1):99.

doi pubmed - Chan SY, Cheung CY, Chan PT, Chau KF. Clozapine-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Hong Kong Med J. 2015;21(4):372-374.

doi pubmed - Parekh R, Fattah Z, Sahota D, Colaco B. Clozapine induced tubulointerstitial nephritis in a patient with paranoid schizophrenia. BMJ Case Rep. 2014;2014:bcr2013203502.

doi pubmed - An NY, Lee J, Noh JS. A case of clozapine induced acute renal failure. Psychiatry Investig. 2013;10(1):92-94.

doi pubmed - Mohan T, Chua J, Kartika J, Bastiampillai T, Dhillon R. Clozapine-induced nephritis and monitoring implications. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013;47(6):586-587.

doi pubmed - Kanofsky JD, Woesner ME, Harris AZ, Kelleher JP, Gittens K, Jerschow E. A case of acute renal failure in a patient recently treated with clozapine and a review of previously reported cases. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2011;13(3):26749.

doi pubmed - Hunter R, Gaughan T, Queirazza F, McMillan D, Shankie S. Clozapine-induced interstitial nephritis - a rare but important complication: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:8574.

doi pubmed - Siddiqui BK, Asim S, Shamim A, Pillai N, Rajan S. Simultaneous allergic interstitial nephritis and cardiomyopathy in a patient on clozapine. NDT Plus. 2008;1(1):55-56.

doi pubmed - Au AF, Luthra V, Stern R. Clozapine-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161(8):1501.

doi pubmed - Estebanez C, Fernandez Reyes MJ, Sanchez Hernandez R, Mon C, Rodriguez F, Alvarez-Ude F, Mampaso F. [Acute interstitial nephritis caused by clozapine]. Nefrologia. 2002;22(3):277-281.

- Fraser D, Jibani M. An unexpected and serious complication of treatment with the atypical antipsychotic drug clozapine. Clin Nephrol. 2000;54(1):78-80.

- Southall KE. A case of interstitial nephritis on clozapine. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2000;34(4):697-698.

doi pubmed - Elias TJ, Bannister KM, Clarkson AR, Faull D, Faull RJ. Clozapine-induced acute interstitial nephritis. Lancet. 1999;354(9185):1180-1181.

doi - Lally J, Al Kalbani H, Krivoy A, Murphy KC, Gaughran F, MacCabe JH. Hepatitis, Interstitial Nephritis, and Pancreatitis in Association With Clozapine Treatment: A Systematic Review of Case Series and Reports. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2018;38(5):520-527.

doi pubmed - Wagner E, Kane JM, Correll CU, Howes O, Siskind D, Honer WG, Lee J, et al. Clozapine combination and augmentation strategies in patients with schizophrenia -recommendations from an international expert survey among the Treatment Response and Resistance in Psychosis (TRRIP) Working Group. Schizophr Bull. 2020;46(6):1459-1470.

doi pubmed - Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.