| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 7, Number 12, December 2016, pages 554-557

Serotonin Syndrome Induced by Combined Use of Tramadol and Escitalopram: A Case Report

Andrea Caamanoa, Rajib Dina, Ahmad Eterb, c

aAvalon University School of Medicine, PO Box 480, Girard, OH 44420, USA

bDepartment of Nephrology/Internal Medicine, Raleigh General Hospital, 1710 Harper Rd, Beckley, WV 25801, USA

cCorresponding Author: Ahmad Eter, Department of Nephrology/Internal Medicine, Raleigh General Hospital, 1710 Harper Rd, Beckley, WV 25801, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication October 27, 2016

Short title: Serotonin Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc2702e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially fatal increase in serotonergic activity in both the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. The etiology can vary from therapeutic drug use, deliberate overdose or drug interactions that all lead to an increase in serotonin activity. There are a number of drugs from different classes that can cause serotonin syndrome either alone at high doses or when combined. We present here a case of a 74-year-old Caucasian female that presented to the emergency room with altered mental status, tachypnea, tachycardia and agitation. She reported taking her usual escitalopram as well as tramadol given to her by a friend to alleviate a headache. She was found tachycardic with a fever of 102.9 °F. She very quickly became combative and had to be sedated and intubated. Laboratory test results were remarkable for severe rhabdomyolysis for which she was treated aggressively with hydration. The patient was extubated on the fifth day after admission once her vitals were stable. Unfortunately, she then developed an intracranial bleed. She was ultimately transferred to another facility with the expectation of being evaluated by a neurosurgeon for the bleed. This patient was diagnosed with serotonin syndrome.

Keywords: Serotonin syndrome; Escitalopram; Tramadol

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Serotonin syndrome is a disorder resulting from excess stimulation of serotonin (5-hydroxytryptamine, 5-HT), especially 5-HT1A and 5-HT2 receptors, in the brainstem and spinal cord [1]. This syndrome can be identified by a sudden onset of a triad of symptoms consisting of cognitive or behavioral changes (agitation, hypomania, and confusion), autonomic instability (hyperthermia, diaphoresis, diarrhea, mydriasis, and tachycardia) and neurologic changes (hyperreflexia, myoclonus, tremor, incoordination, and rigidity) [2].

Serotonin syndrome is a drug-related complication that arises when two or more serotonergic drugs are administered concurrently resulting in a drug interaction causing excessive release of serotonin or blockade of reuptake receptors. The onset of symptoms manifests within 6 - 8 h of the administered dose. Symptoms can range from mild to potentially life-threatening. Other causes such as infection, substance abuse, or withdrawal must be excluded before making a diagnosis of serotonin syndrome [2].

Cases of serotonin syndrome are on the rise, probably due to an increase in the availability and use of serotonergic drugs. It has been observed in all age groups, including newborns and the elderly. The increasing incidence of this condition is thought to parallel the increasing use of serotonergic agents in medical practice [1-3].

Serotonin syndrome is a rare syndrome and can be mistaken for other life-threatening illnesses. The Toxic Exposure Surveillance System reviewed cases from office-based practices, inpatient settings, and emergency departments and found that during 2004, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) caused significant toxic effects in 8,187 persons, leading to 103 deaths [4]. The true incidence of serotonin syndrome and associated morbidity are likely to be much greater. This syndrome may be underdiagnosed given the fact that SSRIs are not the only contributing class of agents. Moreover, it has been suggested that more than 85% of physicians are unaware that the syndrome even exists [5].

| Case Report | ▴Top |

We report here a 74-year-old Caucasian female that presented to the emergency room with altered mental status brought in by a friend. She was found to be tachypnic, tachycardic and febrile. Her family reported that she has regularly taken her escitalopram as prescribed but on the day she presented she had taken an unknown dose of tramadol just hours before the symptoms began. Upon examination, the patient’s blood pressure was 160/120 mm Hg, pulse was 115, respirations was 45, and temperature was 102.9 °F. She was hallucinating and delusional throughout the process. She had to be sedated and intubated. She was admitted to the ICU and developed severe hypertension and autonomic hyperactivity which required a nitroprusside sodium drip as esmolol was not available in the pharmacy. Laboratory test results were remarkable for severe rhabdomyolysis and she was treated with hydration. The patient was extubated on the fifth day after admission once her blood pressure, respiration, and temperature were stable. This patient, unfortunately, started developing some neurological changes as well so a head CT was ordered and revealed a small, 1.7 × 0.6 cm, acute hemorrhage in the right cerebellar hemisphere. She was ultimately transferred to another facility with the expectation of being evaluated by a neurosurgeon for her bleed.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Serotonin syndrome refers to a potentially life-threatening increase in serotonergic activity in the central nervous system and peripheral nervous system. The etiology is often the result of therapeutic drug use, unintentional overdosing of serotonergic agents or complex interactions between drugs that directly or indirectly modulate the serotonin system [4]. There are a number of drugs from different classes that can cause serotonin syndrome either alone at high doses or when combined, which are listed in Table 1 [3, 6-8].

Click to view | Table 1. Examples of Medicines With Potential to Cause Serotonin Syndrome [3, 6-8] |

The increase in intrasynaptic serotonin levels can be achieved by one or more of the following: inhibition of serotonin metabolism, inhibition of serotonin re-uptake, increase in the production/release of serotonin and serotonin receptor agonism.

Tramadol is an opioid pain medication used to treat moderate to moderately severe pain. When taken as an immediate-release oral formulation, the onset of pain relief usually occurs within about an hour. It has two different mechanisms. First, it binds to the μ-opioid receptor. Secondly, it inhibits the re-uptake of serotonin and norepinephrine [9]. While escitalopram is an SSRI approved for the treatment of major depressive disorder in adolescents and adults, and generalized anxiety disorder in adults, escitalopram works by increasing intra-synaptic levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin by blocking the reuptake of the neurotransmitter into the presynaptic neuron [10.] As a result, combination of these two drugs can cause an excessive buildup of serotonin in one’s body. Therefore, there should be an increased awareness when using tramadol for patients who are on antidepressants to prevent future instances of serotonin syndrome.

Differential diagnoses

When making the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome, it is important to keep in mind neuroleptic malignant syndrome (NMS), malignant hyperthermia (MH) and anticholinergic syndrome (AS), which can all present similarly. Table 2 [11-14] outlines these three conditions. NMS is a life-threatening neurological disorder most often caused by an adverse reaction to neuroleptic or antipsychotic drugs. The first symptoms of NMS are usually muscle cramps and tremors, fever, symptoms of autonomic nervous system instability such as unstable blood pressure, and alterations in mental status (agitation, delirium, or coma). Once symptoms appear, they may progress rapidly and reach peak intensity in as little as 3 days. These symptoms can last anywhere from 8 h to 40 days. The muscular symptoms are most likely caused by blockade of the dopamine receptor D2, leading to abnormal function of the basal ganglia similar to that seen in Parkinson’s disease [15]. Treatment may be in the form of dantrolene to decrease muscle rigidity and bromocriptine or amantidine, which both work on dopamine.

Click to view | Table 2. Differential Diagnosis of Serotonin Syndrome [11-14] |

MH occurs in genetically susceptible individuals that are exposed to volatile anesthetic gases such as desflurane, halothane, isoflurane, and enflurane and the muscle relaxants such as succinylcholine, decamethonium, and suxamethonium. The underlying issue is an abnormal ryanodine receptor in skeletal muscle leading to an increase of calcium. A hypercatabolic state ensues and the most common initial sign is an unexpected rise in end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2), which is difficult to decrease as minute ventilation is increased. Generalized muscle rigidity in the presence of neuromuscular blockade is virtually pathognomonic for MH when other signs are present. Most patients with MH do not develop all signs, but they typically present in a similar order: masseter spasm/generalized muscle rigidity, hypercarbia, sinus tachycardia, tachypnea, cyanosis, rapidly increasing temperature up to 105 °F, and elevated temperature. Other signs that may follow include sweating, ventricular tachycardia, dark urine, ventricular fibrillation, and excessive bleeding [16]. Treatment is with dantrolene.

AS results from inhibition of cholinergic neurotransmission at the muscarinic receptor and can be caused by a myriad of prescription and over-the-counter medications. Patients can present with fever, flushing, altered mental status, dry skin, mydriasis, tachycardia, hypertension, myoclonic jerking, trembling and urinary retention. Intervention may be in the form of gastric lavage and possibly activated charcoal to clear the toxins and administration of physostigmine

Diagnostics

The clinical laboratory profile of elevations in creatine kinase, liver function tests and white blood cell count, coupled with a low serum iron level, distinguishes NMS from SS among patients taking neuroleptic and serotonin agonist medications simultaneously. For both SS and NMS, immediate discontinuation of the causative agent is the primary treatment, along with supportive care.

Diagnosis

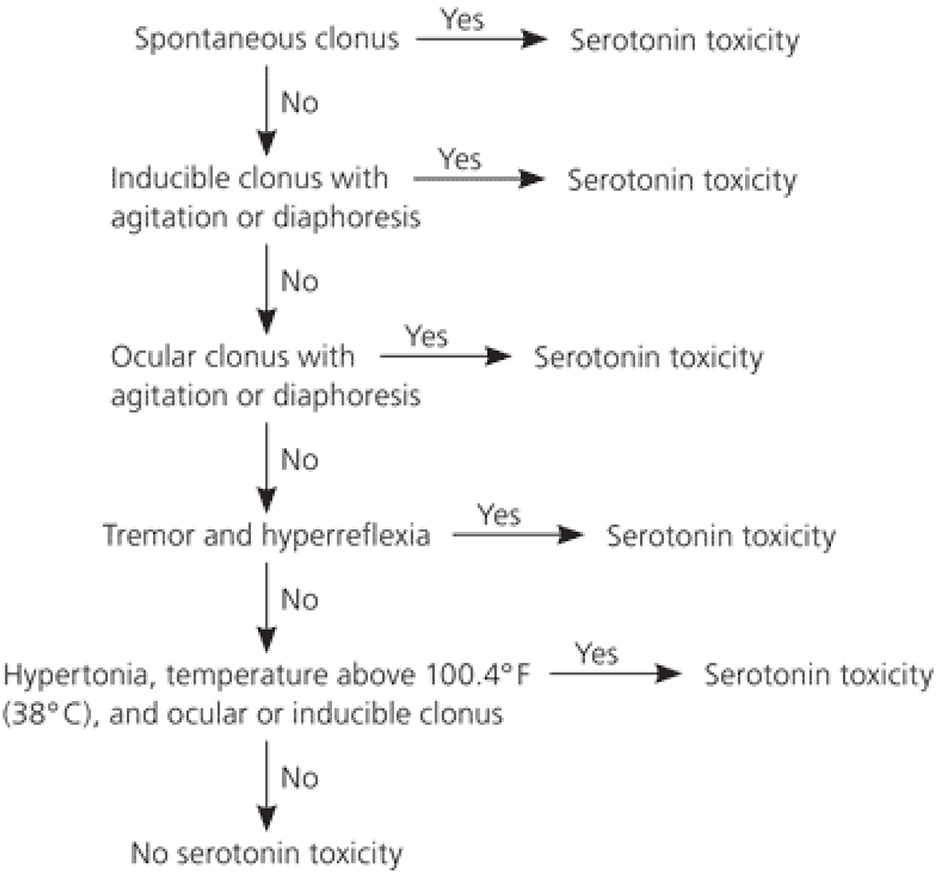

Although history and physical exam are key in making the diagnosis of serotonin syndrome, the Hunter’s serotonin toxicity criteria should be implemented when predicting serotonin syndrome in patients that have knowingly taken a serotonergic agent. Diagnosis with Hunter’s criteria requires one of the following features or groups of features: spontaneous clonus; inducible clonus with agitation or diaphoresis; ocular clonus with agitation or diaphoresis; tremor and hyperreflexia; or hypertonia, temperature above 100.4 °F (38 °C), and ocular or inducible clonus [17]. One must consider other sources of symptoms such as intoxication, withdrawal, infection and metabolic disorder (Fig. 1).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Hunter’s decision rules for diagnosis of serotonin toxicity [12]. |

Symptoms usually begin within 6 - 8 h and the severity of symptoms can span from minimal to life-threatening. Diagnosis is based on a thorough history and physical exam and it is imperative to identify serotonin syndrome early-on in order to provide appropriate treatment for the patient. Symptoms are characterized by a triad of neuron-excitatory features, which include: 1) neuromuscular hyperactivity - tremor, clonus, myoclonus, hyperreflexia and, in advanced stages, pyramidal rigidity; 2) autonomic hyperactivity - diaphoresis, fever, tachycardia and tachypnea; and 3) altered mental status - agitation, excitement and, in advanced stages, confusion [18].

Management

Treatment is mostly supportive and should begin with discontinuation of the offending agent immediately followed by administration of IV fluids. In mild cases, the addition of benzodiazepines to decrease agitation and tremor should suffice. In moderate cases, a serotonin 2A antagonist such as cyproheptadine should be used. Hyperthermia should be aggressively managed with external cooling, hydration, and benzodiazepines (e.g., diazepam and lorazepam). In severe cases, patients with a temperature higher than 105.8 °F should be intubated with induced neuromuscular paralysis. There is a limited role for traditional antipyretics, as the mechanism of serotonin syndrome is due to muscle tone rather than central thermoregulation [19]. Resolution of symptoms usually begins within 24 - 72 h of withdrawal of the offending agent and start of treatment.

Conclusion

This is the first case report of serotonin syndrome due to combination of escitalopram and tramadol use. The use and prevalence of serotonergic drugs for various psychiatric issues is on the rise. As a result, physicians should carefully consider and rule out the clinical diagnosis of serotonin syndrome when presented with an agitated or confused patient with signs and symptoms of serotonin syndrome who is taking serotonergic drugs. One should be hypervigilant when serotonergic drugs are used along with pain medication. The diagnosis mainly depends on the exclusion of certain psychiatric and medical problems first. Clinical symptoms vary from person to person and no pathognomonic laboratory findings are found in serotonin syndrome. Unfortunately, many cases have had fatal outcomes. Physicians need to exercise a reasonable degree of care, awareness and skill to prevent such drug interactions primarily and manage such adverse events. It is imperative to recognize and identify the signs early in order to remove the offending agent and offer supportive care, which are essential to the management of serotonin syndrome and a positive outcome.

| References | ▴Top |

- Birmes P, Coppin D, Schmitt L, Lauque D. Serotonin syndrome: a brief review. CMAJ. 2003;168(11):1439-1442.

pubmed - Sternbach H. The serotonin syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148(6):705-713.

doi pubmed - Boyer EW, Shannon M. The serotonin syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(11):1112-1120.

doi pubmed - Chan BS, Graudins A, Whyte IM, Dawson AH, Braitberg G, Duggin GG. Serotonin syndrome resulting from drug interactions. Med J Aust. 1998;169(10):523-525.

pubmed - Tseng WP, Tsai JH, Wu MT, Huang CT, Liu HW. Citalopram-induced serotonin syndrome: a case report. Kaohsiung J Med Sci. 2005;21(7):326-328.

doi - Ables AZ, Nagubilli R. Prevention, recognition, and management of serotonin syndrome. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(9):1139-1142.

pubmed - Sun-Edelstein C, Tepper SJ, Shapiro RE. Drug-induced serotonin syndrome: a review. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2008;7(5):587-596.

doi pubmed - Yalug I, Ozdemir S, Aker T. A brief review of serotonin syndrome. Neurology, Psychiatry and Brain Research. 2008;15:1-6.

- Brayfield A. "Tramadol Hydrochloride". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. Pharmaceutical Press. 2014.

- Brunton L, Chabner B, Knollman B. Goodman and Gilman's The Pharmacological Basis of Therapeutics, Twelfth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. 2010.

- Jones D, Story DA. Serotonin syndrome and the anaesthetist. Anaesth Intensive Care. 2005;33(2):181-187.

pubmed - Dunkley EJ, Isbister GK, Sibbritt D, Dawson AH, Whyte IM. The Hunter Serotonin Toxicity Criteria: simple and accurate diagnostic decision rules for serotonin toxicity. QJM. 2003;96(9):635-642.

doi pubmed - Ali SZ, Taguchi A, Rosenberg H. Malignant hyperthermia. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003;17(4):519-533.

doi pubmed - Guze BH, Baxter LR, Jr. Current concepts. Neuroleptic malignant syndrome. N Engl J Med. 1985;313(3):163-166.

doi pubmed - Perry PJ, Wilborn CA. Serotonin syndrome vs neuroleptic malignant syndrome: a contrast of causes, diagnoses, and management. Ann Clin Psychiatry. 2012;24(2):155-162.

pubmed - Larach MG, Gronert GA, Allen GC, Brandom BW, Lehman EB. Clinical presentation, treatment, and complications of malignant hyperthermia in North America from 1987 to 2006. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):498-507.

doi pubmed - Ables Adrienne Z, Nagubilli Raju. Spartanburg Family Medicine Residency Program. Spartanburg, South Carolina, Am Fam Physician. 2010;81(9):1139-1142.

pubmed - Gillman PK. Monoamine oxidase inhibitors, opioid analgesics and serotonin toxicity. Br J Anaesth. 2005;95(4):434-441.

doi pubmed - Frank Christopher. FCFP, Recognition and treatment of Serotonin Syndrome. Can Family Physician. 2008;54(7):988-992.

pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.