| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 7, Number 10, October 2016, pages 455-458

Pneumomediastinum: A Complication of Synthetic Cannabinoid K2 Use

Bharat Bajantria, d, Tushi Singhb, Sindhaghatta Venkatrama, c, Gilda Diaz-Fuentesa, c

aDivision of Pulmonary and Critical Care Medicine, Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center, 1650 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center, 1650 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

cClinical Medicine Affiliated With Icahn School of Medicine at Mount Sinai, New York, NY, USA

dCorresponding Author: Bharat Bajantri, Division of Pulmonary, Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center, 1650 Grand Concourse, Bronx, NY 10457, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication September 16, 2016

Short title: Pneumomediastinum due to Cannabinoid K2 Use

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jmc2653w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

The use of synthetic cannabinoid K2 (SCK2) continues to rise. Products are sold in different flavors and mixed with various herbal products resulting in innumerable presenting symptoms. Common presentations are psychomotor activity, dystonia, hypertension, tachydysrhythmia, rhabdomyolysis, and renal failure. We present a 21-year-old woman who was admitted for severe nausea associated with several bouts of vomiting and upper abdominal pain. She had used SCK2 for recreation prior to the onset of her symptoms and she has been using SCK2 regularly for about a year. Chest and abdomen roentgenogram revealed pneumomediastinum. Esophagogram ruled out esophageal injury. She was managed conservatively with resolution of pneumomediastinum. We hypothesize that hyperemesis secondary to SCK2 use can increase the alveolar pressure leading to barotrauma. Although pneumomediastinum is a benign and self-limiting condition, esophagogram should be performed to exclude esophageal perforation which is a potentially life-threatening condition. Awareness of this presentation is important in order to evaluate for complications of barotrauma.

Keywords: Pneumomediastinum; Spice; K2; Synthetic marijuana

| Introduction | ▴Top |

The use of synthetic cannabinoid K2 (SCK2) continues to rise. These products are sold in different flavors and mixed with various herbal products resulting in innumerable clinical presentations. The most common manifestations are anxiety, tremors, hypertension, tachycardia, and tachy-dysrhythmia. Chest pain is a common complaint, and a case of myocardial infarction and death has been reported [1]. Due to the increased psychomotor activity and dystonia, rhabdomyolysis and renal failure have been also reported [2, 3]. We present a young patient with complications of SCK2 abuse.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 21-year-old woman with history of polysubstance abuse was admitted to the intensive care unit with severe nausea associated with several bouts of vomiting and upper abdominal pain of 3 days duration. Symptoms started after using SCK2. She had two prior hospital visits due to similar complaints, which resolved spontaneously with hydration. She reported being a regular smoker of marijuana for the past 2 - 3 years and she started using spice/K2 for recreation in the last few months. She denied use of alcohol or other recreational agents. She had no other personal or family medical history.

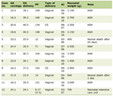

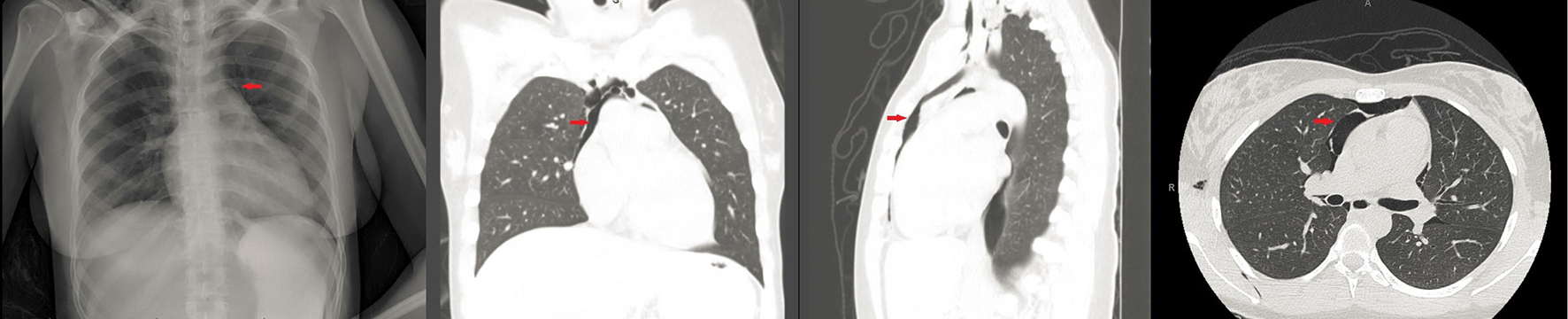

On examination, she had respiratory distress, were afebrile, normotensive, tachycardic (HR 105 beats per minute), and tachypneic (RR 20 cycles per minute) and had a body mass index of 20.3 kg/m2. Lung was clear to auscultation, and cardiovascular was normal. Mild diffuse tenderness was elicited on epigastric exam with no rebound tenderness or visceromegaly. Laboratory investigations revealed leukocytosis, acute kidney injury and anion gap metabolic acidosis (Table 1). Urine toxicology revealed cannabinoids. Abdominal computed tomogram (CT) revealed pneumomediastinum which was confirmed by a chest CT (Fig. 1). Esophagogram ruled out esophageal injury. She was managed conservatively with resolution of pneumomediastinum. Echocardiogram was normal.

Click to view | Table 1. Laboratory Results |

Click for large image | Figure 1. CXR and sagittal and coronal view of chest CT. Red arrow points to pneumomediastinum. Normal lung parenchyma. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

SCs were initially developed to serve as an analgesic with a mechanism of action different from opiods and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. This led to the discovery of cannabinoid (CB) receptors [3-5]. Activation of CB receptors causes elation, irritability and anxiety. CB receptors are located in the immune system and podocytes in glomeruli [3-8]. They are thought to play a role in control of pain and emesis. SCs are full agonists of CB receptors with biologically active metabolites [9-11].

SCs are in vogue, especially among the young generation who use it for relaxation and recreation without being detected on routine toxicology screens [10, 12].

Some of the common side effects of SCs include altered mentation, hypertension, tachycardia, arrhythmias, myocardial ischemia, seizures, nausea, vomiting, and electrolyte abnormalities. All these can lead to multi-organ dysfunction, acute kidney injury and severe rhabdomyolysis [1-3, 13-18]. Cannabinoids have also been found to have caused fulminant liver failure and pulmonary edema [14]. Neuropsychiatric effects include confusion, agitation, aggression, psychosis and dependence [2, 15-19]. K2 or spice, one of the formulations of SCs causes tachycardia, diaphoresis, conjunctival injection, hypokalemia and seizures [20, 21]. Chronic use of SCs has been reported to cause acute gastric dilation and hepatic portal venous gas that is postulated to be mediated by CB receptors. Chronic hyperemesis syndrome (CHS) is also mediated by CB receptors in the gastric mucosa; the syndrome is characterized by chronic cannabis use, cyclic episodes of nausea and vomiting and frequent hot bathing. SCK2 owing to the molecular similarity with cannabinoids can potentially cause this syndrome. Some reports suggest that warm water ameliorates symptoms of CHS [22].

Pneumomediastinum is classified as non-traumatic (primary or spontaneous) and traumatic (secondary). The cause of pneumomediastinum is alveolar rupture related to an increase in alveolar pressure, resulting in pressure gradient between alveoli and surrounding blood vessel. Common causes of increased alveolar pressure in a normal lung include trauma, coughing, emesis, Valsalva maneuver and airway obstruction. Usual clinical presentations of pneumomediastinum include chest pain aggravated by deep breathing and coughing, dyspnea, dysphagia and rarely shocking sensation. The exam may reveal subcutaneous emphysema or crepitus appreciated over the neck and anterior chest wall. Hamman’s mediastinal crunch may be appreciated [23].

The diagnosis of pneumomediastinum can be made by a chest roentgenogram showing the continuous diaphragm sign and prominent aortic knob. Lateral view showing air in the retrosternal space is more sensitive. Chest CT has the greatest sensitivity. In a study that evaluated the sensitivity and specificity of CT scan for detection of pneumomediastinum after blunt chest trauma, it was found that CT chest had 89% sensitivity for detection of pneumomediastinum [24]. Another study showed that the negative predictive value and sensitivity for detecting esophageal rupture on CT chest with or without contrast was 100% in trauma and non-trauma patients [25]. Our patient experienced recurrent vomiting following use of K2 which most likely resulted in pneumomediastinum [26, 27].

The effects of SC in the lungs range from non-specific pulmonary infiltrates, pulmonary hemorrhage and acute respiratory failure likely due to allergic alveolitis [28]. Cannabinoids cause inflammatory responses in the airways and lung parenchyma leading to histopathological changes [28]. There are cases reporting barotrauma associated with recreational substance especially with cocaine and marijuana [29, 30]. Pneumothorax and pneumomediastinum secondary to a positive pressure device used for smoking/inhaling the drugs have been reported. Spontaneous or primary pneumomediastinum is postulated to be secondary to increased intra-alveolar pressure. Underlying lung parenchymal inflammation weakens the alveolar wall, thus making it more vulnerable for alveolar web rupture [30].

Diagnosis of SC-related complications remains a challenge, as there are many substances mixed in each preparation of these drugs. Liquid chromatography and homogenous enzyme immuno-assay (HEIA) spectrometry have been proposed as diagnostic methods [31, 32]. Sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency of HEIA K2 spice kit is based on quantitative cut-off points. Based on the trails, the manufacturer’s recommended cut-off point was 10 μg/L. The sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency for that cut-off were 75.6%, 99.6% and 96.8%, respectively [31]. Management of SC/K2 intoxication is mainly supportive, aimed at fluid resuscitation, airway protection, management of electrolyte imbalance and minimizing organ damage. Intravenous lipid emulsion therapy has been used in few cases of acute intoxication with promising results [33].

Our patient presented with typical manifestations of SC toxicity which included hyponatremia, severe rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, hyperglycemia and possible CHS. We attribute pneumomediastinum due to increased alveolar pressure due to two pathophysiological mechanisms. First is Valsalva maneuvers during inhalation of the drug and second is CHS with recurrent vomiting. Due to the relative short duration of K2 and normal lung parenchyma, it is unlikely that the patient had a direct pulmonary insult leading to barotrauma [34].

Conclusion

Increasing incidence of cannabinoids use among adolescents and young adults, and the difficulties in detection on routine toxicology screening tests present a challenge for clinicians. A low clinical suspicion for complications of SC is required especially when confronted with young patients with a myriad of symptoms. Development of novel screening techniques is needed. Use of SCK2 should be included in the differential diagnosis of barotraumas, with patients with CHS likely having an increased risk for it. Esophagogram should be considered to exclude esophageal perforation.

Consent

Written informed consent was obtained for the patient for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

Abbreviations

SCK2: synthetic cannabinoid K2; JWH-018: 1-pentyl-3-(1-naphthoyl)indole; CB: cannabinoid; SC: synthetic cannabinoid; CHS: chronic hyperemesis syndrome; HEIA: homogenous enzyme immuno-assay

| References | ▴Top |

- Ibrahim S, Al-Saffar F, Wannenburg T. A Unique Case of Cardiac Arrest following K2 Abuse. Case Rep Cardiol. 2014;2014:120607.

doi - Antoniou T, Juurlink DN. Synthetic cannabinoids. CMAJ. 2014;186(3):210.

doi pubmed - Kazory A, Aiyer R. Synthetic marijuana and acute kidney injury: an unforeseen association. Clin Kidney J. 2013;6(3):330-333.

doi pubmed - Wiley JL, Marusich JA, Huffman JW, Balster RL, Thomas BF. Hijacking of Basic Research: The Case of Synthetic Cannabinoids. Methods Rep RTI Press. 2011;2011.

doi - Sethi R, Thapa N, Saxena A, Chahil R. "K2/Spice": have you updated your differentials? A case report. Prim Care Companion CNS Disord. 2013;15(2).

doi - Ustundag MF, Ozhan Ibis E, Yucel A, Ozcan H. Synthetic cannabis-induced mania. Case Rep Psychiatry. 2015;2015:310930.

doi - de Havenon A, Chin B, Thomas KC, Afra P. The secret "spice": an undetectable toxic cause of seizure. Neurohospitalist. 2011;1(4):182-186.

doi pubmed - Tai S, Fantegrossi WE. Synthetic Cannabinoids: Pharmacology, Behavioral Effects, and Abuse Potential. Curr Addict Rep. 2014;1(2):129-136.

doi pubmed - Tiedeman JS, Shields MB, Weber PA, Crow JW, Cocchetto DM, Harris WA, Howes JF. Effect of synthetic cannabinoids on elevated intraocular pressure. Ophthalmology. 1981;88(3):270-277.

doi - Fattore L, Fratta W. Beyond THC: The New Generation of Cannabinoid Designer Drugs. Front Behav Neurosci. 2011;5:60.

doi pubmed - Rajasekaran M, Brents LK, Franks LN, Moran JH, Prather PL. Human metabolites of synthetic cannabinoids JWH-018 and JWH-073 bind with high affinity and act as potent agonists at cannabinoid type-2 receptors. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2013;269(2):100-108.

doi pubmed - Hu X, Primack BA, Barnett TE, Cook RL. College students and use of K2: an emerging drug of abuse in young persons. Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2011;6:16.

doi pubmed - Bhutia SC, Singh TA, Sherpa ML. Correlation of the Osteogenic Protein-1 (OP-1) with Age, Cartilage metabolic Markers and Antioxidants in the Osteoarthritic Patients of Sikkim. J Clin Diagn Res. 2013;7(8):1565-1567.

doi - Behonick G, Shanks KG, Firchau DJ, Mathur G, Lynch CF, Nashelsky M, Jaskierny DJ, et al. Four postmortem case reports with quantitative detection of the synthetic cannabinoid, 5F-PB-22. J Anal Toxicol. 2014;38(8):559-562.

doi pubmed - Karila L, Megarbane B, Cottencin O, Lejoyeux M. Synthetic cathinones: a new public health problem. Curr Neuropharmacol. 2015;13(1):12-20.

doi pubmed - Cottencin O, Rolland B, Karila L. New designer drugs (synthetic cannabinoids and synthetic cathinones): review of literature. Curr Pharm Des. 2014;20(25):4106-4111.

doi pubmed - Sherpa D, Paudel BM, Subedi BH, Chow RD. Synthetic cannabinoids: the multi-organ failure and metabolic derangements associated with getting high. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2015;5(4):27540.

doi - Heath TS, Burroughs Z, Thompson AJ, Tecklenburg FW. Acute intoxication caused by a synthetic cannabinoid in two adolescents. J Pediatr Pharmacol Ther. 2012;17(2):177-181.

doi - Spaderna M, Addy PH, D'Souza DC. Spicing things up: synthetic cannabinoids. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2013;228(4):525-540.

doi pubmed - Lapoint J, James LP, Moran CL, Nelson LS, Hoffman RS, Moran JH. Severe toxicity following synthetic cannabinoid ingestion. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49(8):760-764.

doi pubmed - Rosenbaum CD, Carreiro SP, Babu KM. Here today, gone tomorrow...and back again? A review of herbal marijuana alternatives (K2, Spice), synthetic cathinones (bath salts), kratom, Salvia divinorum, methoxetamine, and piperazines. J Med Toxicol. 2012;8(1):15-32.

doi pubmed - Ukaigwe A, Karmacharya P, Donato A. A Gut Gone to Pot: A Case of Cannabinoid Hyperemesis Syndrome due to K2, a Synthetic Cannabinoid. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2014;2014:167098.

doi - Wilkinson CG, Adams PC. Pneumomediastinum in a trumpeter diagnosed by the presence of Hamman's crunch. BMJ Case Rep. 2012;2012.

- Dissanaike S, Shalhub S, Jurkovich GJ. The evaluation of pneumomediastinum in blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2008;65(6):1340-1345.

doi pubmed - Wu CH, Chen CM, Chen CC, Wong YC, Wang CJ, Lo WC, Wang LJ. Esophagography after pneumomediastinum without CT findings of esophageal perforation: is it necessary? AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(5):977-984.

doi pubmed - Clement R, Bresson C, Rodat O. Spontaneous oesophageal perforation. J Clin Forensic Med. 2006;13(6-8):353-355.

doi pubmed - Mutter D, Evrard S, Hemar P, Keller P, Schmidt C, Marescaux J. [Boerhaave syndrome or spontaneous rupture of the esophagus]. J Chir (Paris). 1993;130(5):231-236.

- Alhadi S, Tiwari A, Vohra R, Gerona R, Acharya J, Bilello K. High times, low sats: diffuse pulmonary infiltrates associated with chronic synthetic cannabinoid use. J Med Toxicol. 2013;9(2):199-206.

doi pubmed - Mayaud C, Boussaud V, Saidi F, Parrot A. [Bronchopulmonary disease in drug abusers]. Rev Pneumol Clin. 2001;57(4):259-269.

pubmed - Luque MA, 3rd, Cavallaro DL, Torres M, Emmanual P, Hillman JV. Pneumomediastinum, pneumothorax, and subcutaneous emphysema after alternate cocaine inhalation and marijuana smoking. Pediatr Emerg Care. 1987;3(2):107-109.

doi pubmed - Barnes AJ, Young S, Spinelli E, Martin TM, Klette KL, Huestis MA. Evaluation of a homogenous enzyme immunoassay for the detection of synthetic cannabinoids in urine. Forensic Sci Int. 2014;241:27-34.

doi pubmed - Namera A, Kawamura M, Nakamoto A, Saito T, Nagao M. Comprehensive review of the detection methods for synthetic cannabinoids and cathinones. Forensic Toxicol. 2015;33(2):175-194.

doi pubmed - Aksel G, Guneysel O, Tasyurek T, Kozan E, Cevik SE. Intravenous Lipid Emulsion Therapy for Acute Synthetic Cannabinoid Intoxication: Clinical Experience in Four Cases. Case Rep Emerg Med. 2015;2015:180921.

doi - Pendergraft WF, 3rd, Herlitz LC, Thornley-Brown D, Rosner M, Niles JL. Nephrotoxic effects of common and emerging drugs of abuse. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2014;9(11):1996-2005.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.