| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 10, October 2013, pages 679-681

A Cavitary Conundrum

Sajan Andrewsa, Jared Isaacsona, Emmy Heberta, Saspin Nakornsrib, Hythem Omara, c

aUT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390, USA

bDallas County Hospital District, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390, USA

cCorresponding author: Hythem Omar, UT Southwestern Medical Center, 5323 Harry Hines Blvd. Dallas, TX 75390, USA

Manuscript accepted for publication August 20, 2013

Short title: Cavitary Conundrum

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc1471w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in the male population after skin cancer. Approximately 220,000 men in the United States are diagnosed with prostate cancer annually, 29,000 of which succumb to the disease. In the overwhelming majority of cases, metastatic prostate cancer presents with an elevated PSA and osseous involvement. We present a unique case of cavitary nodular prostate metastases to the lung without osseous involvement and a normal PSA. A brief discussion of cavitary lung lesions is also covered.

Keywords: Prostate; Cavitary nodule; PSA

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Prostate cancer is the second most common cancer in the male population after skin cancer. Approximately 220,000 men in the United States are diagnosed with prostate cancer annually, 29,000 of which succumb to the disease [1]. The development and utilization of the screening Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) test has reduced the frequency of presentation of advanced disease in recent decades with approximately 3.2% of patients presenting with distant disease. However, given the frequency of prostate cancer, many cases with distant disease are discovered at initial diagnosis [2]. A wide variety of prostate cancer presentations are possible. Prior case reports detail prostate cancer initially presenting as supraclavicular lymphadenopathy [3, 4]. A recent report of hydronephrosis secondary to ureteral implantation was published in 2012 [5].

Cavitary pulmonary nodules have a variety of causes including benign and malignant etiologies. However, prostate cancer metastases are not part of the usual differential, especially in the setting of normal PSA and bone scan. We present a unique case of cavitary nodular prostate metastases to the lung without osseous involvement and a normal PSA. A brief discussion of cavitary lung lesions is also covered.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 74-year-old man with a 2 year history of T3NxMx poorly differentiated Gleason 4 + 4 = 8 adenocarcinoma of the prostate presented for routine follow-up. At the time of diagnosis two years prior, his PSA was 24.0 ng/mL (normal reference range 0.0 - 4.0 ng/mL). He was treated with local radiation and systemic Lupron.

On presentation, he had no pertinent complaints. Vital signs were within normal limits including an oxygen saturation of 98% on room air and a normal respiratory rate. Laboratory testing was notable for a normal PSA at 1.44 g/mL. Complete blood count and chemistry panel were also within normal limits. Physical examination of the chest, cardiovascular system and abdomen were unremarkable.

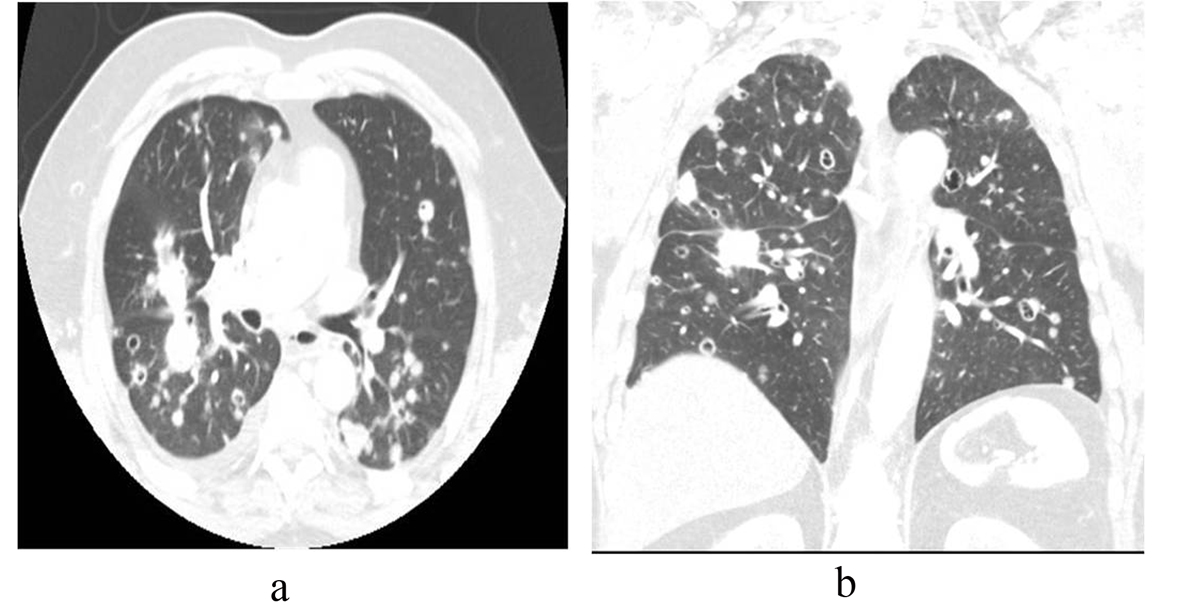

The patient had known small pulmonary nodules that were stable over sequential exams. Routine chest radiograph and staging computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis were performed revealing interval development of new pulmonary nodules and enlargement of others (Fig. 1, 2). Many of the nodules had become cavitary. No osseous lesions were identified and subsequent nuclear medicine bone scan showed no scintigraphic evidence of bony metastases.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Frontal radiograph of the chest showing multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. (a) Axial and (b) coronal CT images in lung windows show multiple bilateral pulmonary nodules of varying sizes, some cavitary. |

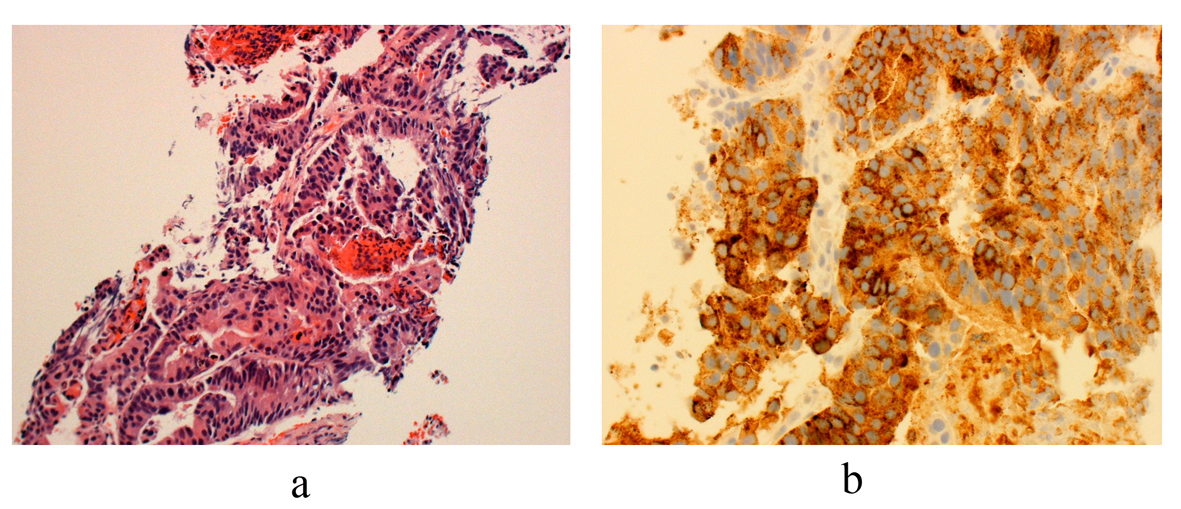

Percutaneous CT guided biopsy of one of the cavitary lung lesions was performed which revealed metastatic prostate adenocarcinoma, consistent with the known primary (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. (a) Histology from core biopsy demonstrates malignant glands consistent with an adenocarcinoma (hemotoxylin-esosin stain 10 ×). (b) Staining for prostate acid phosphatase (PSAP) confirms the diagnosis of metastatic prostatic adenocarcinoma (immunostain for PSAP 20 ×). |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Literature reports an incidence of clinically apparent pulmonary metastases in 5-27% of prostate cancer patients [6, 7]. These metastases are overwhelmingly seen only after bone metastases have occurred and generally present in one of two basic radiological patterns. The most common radiologic presentation is that of lymphangitic spread illustrated by diffuse interstitial thickening/nodularity. Hematologic spread presenting as multiple pulmonary nodules is identified in 8 to 20% [6, 7]. Solitary cavitating pulmonary metastasis has been reported in the literature but is extremely rare [7-10]. Almost all patients with metastatic prostate cancer present with a high PSA level, thereby enabling the marker to be used as a measure of disease burden/response to treatment. Less than 1% of metastatic prostate cancer cases have low serum PSA levels [11]. To the authors’ knowledge, metastatic prostate cancer to the lungs presenting as multiple bilateral cavitary lung lesions without bony metastases and normal PSA has not been previously reported.

Multiple cavitary pulmonary nodules have a diverse differential, including benign and malignant etiologies. Benign entities may be infectious in nature such as septic emboli, fungal, atypical (mycobacterial), and aspiration pneumonia. Noninfectious benign causes include sarcoidosis, pneumoconiosis, and collagen vascular/connective tissue disorders like rheumatoid arthritis and Wegener’s granulomatosis [12]. Malignant etiologies include primary and metastatic cancers. Of primary lung neoplasms, squamous cell carcinomas most frequently cavitate but usually present as a single lesion. Furthermore, extra-pulmonary squamous cell carcinomas are the most common type of cavitating metastases, composing 69% of such lesions. Other rare reported cases of cavitary transitional cell carcinoma, adenocarcinomas and sarcomas are documented in literature [13]. Vascular insufficiency eventually leads to necrosis and cavitation in pulmonary metastases. Vascular compromise may be secondary to direct involvement or tumor outgrowth of blood supply [14].

The prognosis of prostate cancer is mainly determined by the presence or absence of metastases. Among 19,316 routine autopsies performed from 1967 to 1995 on men older than 40 years of age, reports from 1,589 (8.2%) with prostate cancer were analyzed by Bubendorf L. and associates. When hematogeneous metastases were present, skeletal involvement was found in 90%. Spine involvement was more common with smaller tumors (4 to 6 cm) as compared with lung metastases (6 to 8 cm), suggesting a temporal relationship between sites of metastases with spine metastases preceding lung involvement [15].

The mainstay of treatment for patients with pulmonary metastases, as with other sites of metastases, is hormonal therapy [6, 16]. Furthermore, the prognosis for patients with hormone-naive disease and pulmonary metastases is not necessarily worse than those with metastatic disease at other sites. The overall survival is longer in cases of hormone-naive disease and pulmonary metastases than with hormone-refractory disease and pulmonary metastases [6].

Investigation of theories regarding the interaction of tumor cells and the microenvironment at distant sites may provide clinicians with greater understanding of the varied behavior of malignant, metastatic prostate cancer [17]. Also, research into the biological features of circulating tumor cells involved in the hematogenous spread of metastatic cancer may also improve clinical understanding of such processes [18].

| References | ▴Top |

- U.S. Cancer Statistics Working Group, United States Cancer Statistics: 1999-2006 Incidence and Mortality Web-Based Report, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and National Cancer Institute, Atlanta, Ga, USA, 2010

- Li J, Djenaba JA, Soman A, Rim SH, Master VA. Recent trends in prostate cancer incidence by age, cancer stage, and grade, the United States, 2001-2007. Prostate Cancer. 2012;2012:691380.

- Chan G, Domes T. Supraclavicular lymphadenopathy as the initial presentation of metastatic prostate cancer: A case report and review of literature. Can Urol Assoc J. 2013;7(5-6):E433-435.

pubmed - Jones H, Anthony PP. Metastatic prostatic carcinoma presenting as left-sided cervical lymphadenopathy: a series of 11 cases. Histopathology. 1992;21(2):149-154.

doi - Schneider S, Popp D, Denzinger S, Otto W. A rare location of metastasis from prostate cancer: hydronephrosis associated with ureteral metastasis. Adv Urol. 2012;2012:656023.

doi pubmed - Fabozzi SJ, Schellhammer PF, el-Mahdi AM. Pulmonary metastases from prostate cancer. Cancer. 1995;75(11):2706-2709.

doi - Goto T, Maeshima A, Oyamada Y, Kato R. Solitary pulmonary metastasis from prostate sarcomatoid cancer. World J Surg Oncol. 2010;8:101.

doi pubmed - Hofland CA, Bagg MD. An isolated pulmonary metastasis in prostate cancer. Mil Med. 2000;165(12):973-974.

pubmed - Smith CP, Sharma A, Ayala G, Cagle P, Kadmon D. Solitary pulmonary metastasis from prostate cancer. J Urol. 1999;162(6):2102.

doi - Crawford ED, Nabors WL. Total androgen ablation: American experience. Urol Clin North Am. 1991;18(1):55-63.

pubmed - Lee DK, Park JH, Kim JH, Lee SJ, Jo MK, Gil MC, Song KH, et al. Progression of prostate cancer despite an extremely low serum level of prostate-specific antigen. Korean J Urol. 2010;51(5):358-361.

doi pubmed - Mandel J, Stark P. Differential diagnosis and evaluation of Multiple Pulmonary Nodules, topic. In UpToDate, Waltham, MA, 2007.

- Seo JB, Im JG, Goo JM, Chung MJ, Kim MY. Atypical pulmonary metastases: spectrum of radiologic findings. Radiographics. 2001;21(2):403-417.

pubmed - Chaudhuri MR. Cavitary pulmonary metastases. Thorax. 1970;25(3):375-381.

doi pubmed - Bubendorf L, Schopfer A, Wagner U, Sauter G, Moch H, Willi N, Gasser TC, et al. Metastatic patterns of prostate cancer: an autopsy study of 1,589 patients. Hum Pathol. 2000;31(5):578-583.

doi pubmed - White AC, An-Foraker SH, Cohn A, Sicilian L. Solitary cavitating pulmonary metastasis from prostatic carcinoma. Am J Med. 1990;88(2):193-195.

doi - Langley RR, Fidler IJ. The seed and soil hypothesis revisited—the role of tumor-stroma interactions in metastasis to different organs. Int J Cancer. 2011;128(11):2527-2535.

doi pubmed - Liberko M, Kolostova K, Bobek V. Essentials of circulating tumor cells for clinical research and practice. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2013.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.