| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website https://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 13, Number 9, September 2022, pages 449-455

Steven-Johnson Syndrome: A Rare but Serious Adverse Event of Nivolumab Use in a Patient With Metastatic Gastric Adenocarcinoma

Eltaib Saada, c, Pabitra Adhikaria, Drashti Antalaa, Ahmed Abdulrahmana, Valiko Begiashvilia, Khalid Mohameda, Elrazi Alib, Qishou Zhanga

aDepartment of Internal Medicine, Ascension Saint Francis Hospital, Evanston, IL, USA

bDepartment of Internal Medicine, One Brooklyn Health, Interfaith Medical Center, Brooklyn, NY, USA

cCorresponding Author: Eltaib Saad, Department of Internal Medicine, Ascension Saint Francis Hospital, Evanston, IL, USA

Manuscript submitted August 2, 2022, accepted August 24, 2022, published online September 28, 2022

Short title: Steven-Johnson Syndrome

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jmc3992

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Nivolumab is a humanized monoclonal anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 (PD-1) antibody that has been authorized for use in the treatment of advanced malignancies. Cutaneous reactions are the most common immune-related adverse events reported with anti-PD-1 agents, and they range broadly from mild localized reactions to rarely severe or life-threatening systemic dermatoses. The occurrence of Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) with nivolumab use is an exceedingly rare phenomenon that was only documented in a handful of cases in the current literature, but it deserves careful attention as SJS/TEN may be associated with fatal outcomes. We present a case of nivolumab-induced SJS/TEN in a middle-aged female patient with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma that was successfully treated with immunosuppressive therapy and supportive care. Prompt recognition of SJS/TEN with discontinuation of nivolumab is warranted when SJS/TEN is suspected clinically. Multidisciplinary management in a specialized burn unit is the key to improving outcomes of SJS/TEN.

Keywords: Anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 agents; Cutaneous adverse reactions; Immune checkpoint; Nivolumab; Steven-Johnson syndrome; Rare

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Anti-programmed cell death receptor-1 (anti-PD-1) agents have been increasingly used for the treatment of advanced malignancies in modern oncology practice [1, 2]. Anti-PD-1 agents have positively impacted the outcome of some metastatic cancers with substantial improvement in the life expectancy of the affected patients [1, 2]. Anti-PD-1 agents are targeted monoclonal antibodies against certain immune checkpoint molecules in the signaling of downstream cascades of inflammatory and immune pathways (such as programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) receptors or their ligands (PD-L1) and cytotoxic T lymphocytes-associated antigen-4 (CTLA-4) [3].

Numerous immune-related adverse events (irAEs) have emerged with the recent use of these novel agents due to the disturbance of the physiological pathways that maintain a state of peripheral immune tolerance [3], with the cutaneous reactions being considered the most frequent adverse events described with immune checkpoint inhibitors [1, 2]. The cutaneous irAEs range considerably from mild localized reactions that are relatively common and largely manageable (including, for instance, pruritis, lichenoid reactions, maculopapular rashes, and granulomatous skin disorders) to rare systemic conditions that may be associated with serious or life-threatening outcomes like Steven-Johnson syndrome (SJS) or toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) [1, 2, 4]. Although yet to be completely understood, SJS/TEN is believed to be a drug-related cytotoxic reaction that induces massive apoptosis of keratinocytes [5].

Herein, we present a case of SJS/TEN in a middle-aged female patient with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma after treatment with nivolumab. A comprehensive literature review was conducted to summarize all the published cases of nivolumab-associated SJS/TEN.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

Investigations

A 45-year-old female with a past medical history of gastric adenocarcinoma with hepatic and bony metastasis (proximal humeral and iliac metastatic diseases) presented to the emergency department for evaluation of skin rash. The patient reported a rash on the right shoulder and the right upper extremity that progressed to involve her torso and lower extremities with the development of painful blisters over a course of 1 week. She denied fevers, rigors, sore throat, eye swelling or discharge, fatigue, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, or joint swelling.

The patient had received three cycles of nivolumab and five cycles of FOLFOX (oxaliplatin, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin), with the last dose of nivolumab administered 2 weeks prior to the onset of skin rash. The patient also received radiation therapy to the right hip, right shoulder, and left thigh 1 week prior to index presentation. The patient was not known to have a known drug allergy. No use of Chinese medicines or herbal supplements (CAM) was reported by the patient.

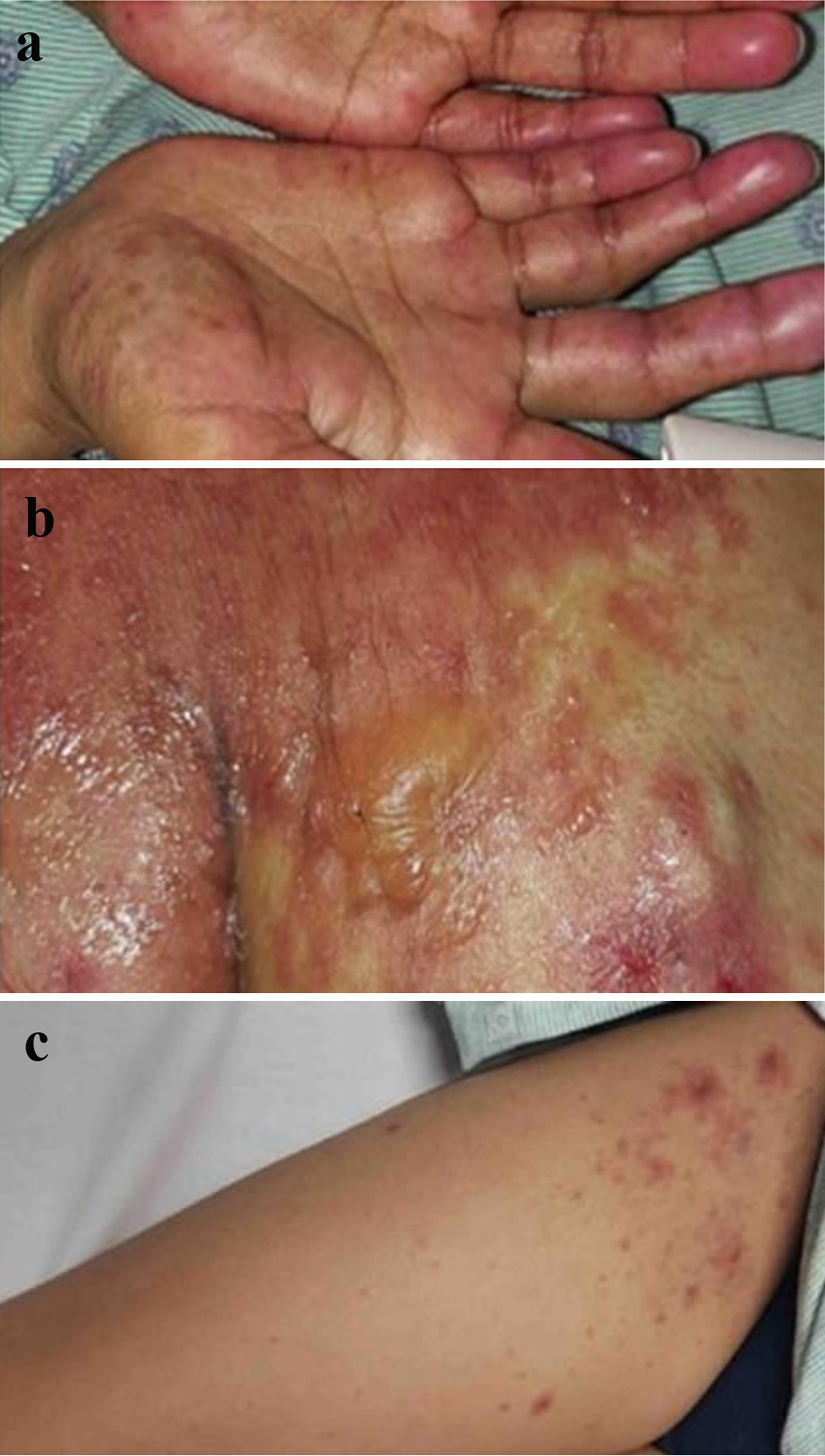

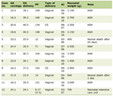

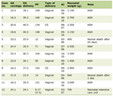

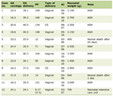

General examination revealed a toxic-looking patient who was afebrile (temperature of 37 °C), tachypneic (respiratory rate of 24 breaths/min), hypotensive to 85/55 mm Hg, and tachycardic to 110 beats/min. The physical examination was notable for diffuse skin rash with various evolution stages, including confluent maculopapular rash with scattered erosions, sloughing, and crusts, alongside vesicles and hyperpigmented plaques involving lips and oral mucosa, bilateral hands (Fig. 1a), right shoulder (Fig. 1b), right upper extremity (Fig. 1c), thighs, and gluteal region. Approximately 15% of total body surface area (BSA) demonstrated skin eruption with a positive Nikolsky sign. Table 1 summarizes relevant laboratory results (with reference ranges) on admission.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) A confluent papular rash over both hands. (b) Erupted rash with vesicles and bullae over the right shoulder. (c) A maculopapular rash over the right upper extremity. |

Click to view | Table 1. Pertinent Laboratory Results on Admission |

Diagnosis

At this point, the differential diagnosis included radiation-induced dermatitis exacerbated by an immune checkpoint inhibitor (i.e., nivolumab), SJS/TEN overlap, or drug rash secondary to 5-fluorouracil or oxaliplatin. However, the confluent nature of the eruptive rash, evidence of bullae and vesicles, presence of mucocutaneous lesions, and involvement of areas that were not subjected to radiotherapy, e.g., hands and feet strongly favor a diagnosis of SJS/TEN. Nivolumab was discontinued given the clinical suspicion of STS/TEN overlap.

A skin biopsy of one of the right upper extremity lesions revealed focal full-thickness necrosis of the epidermis, interface dermatitis, mild perivascular mixed inflammatory cell infiltrate with eosinophils in the dermis, and diffuse subepidermal splitting confirming a final diagnosis of SJS. A clinical diagnosis of SJS/TEN overlap was considered based on the total BSA involved by the erupted rash. Calculated SCORTEN was 4 (age > 40 years, associated malignancy, affected TBS > 10%, and serum bicarbonate < 20 mmol/L) which was associated with a 58.3% mortality rate.

Treatment

A multidisciplinary team, including critical care, oncology, dermatology, nutritional services, and burn teams was involved in patient care given the predicated fatal outcome of SJS/TEN overlap. The patient was admitted to a specialized burn intensive care unit (ICU) and started on prednisone at 1 mg/kg daily, which was tapered when the rash improved to grade 1 dermatitis (evident by faint erythema, regression of skin involvement to < 10% BSA, and minimal pain). The patient was commenced on topical steroids given the possibility of radiation dermatitis. Critical supportive care with hydration, nutritional supplements, adequate analgesia, and standard wound care was provided.

Follow-up

The patient’s rash continued to improve with gradual healing of the erupted skin. She was discharged with closed outpatient follow-up with oncology and dermatology services.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Immune checkpoint molecules (such as PD-1 and CTLA-4) are essentially inhibitory regulators that serve to maintain a physiological state of immune tolerance against self-antigens in the peripheral tissues by attenuating the cytotoxic effects of immune cells through complex signaling pathways [6]. The expression of CTLA-4 on the regulatory T cells in the lymphoid organs during the priming phase primarily mediates an overall inhibitory effect on the cellular immune system [6]. PD-1 is a receptor expressed on the activated B cells and T cells; the interaction between PD-1 and their ligands (PD-L1) prevents autoimmunity by mediating an inhibitory effect on the effector cells through the suppression of T cells activation against self-antigens in the periphery [7]. However, PDL-1 is overexpressed by tumor cells and the tumor microenvironment (TME) to escape themselves from the host immune system via attenuation of effector T cells’ activities against tumor cells [6, 7].

Anti-PD1 agents are immune checkpoint inhibitors that block the interactions between PD-1 and PD-L1, resulting in the promotion of activated T cells to enhance their intrinsic ant-tumor effects, and thus suppressing tumor growth [6, 7]. Nevertheless, an exaggerated response to the latter T cells activation may also trigger a loss of self-tolerance, eventually accumulating in the occurrence of irAEs [8].

IrAEs encompass a broad spectrum of various organ-specific syndromes (i.e., cutaneous reactions, arthritis, colitis, pneumonitis, thyroiditis, and hypophysitis) [1, 3, 6-8] with different grades of severity that are classified according to the criteria of Common Terminology of Adverse Events (CTAEs) [9]. It was estimated that almost half of patients (49%) treated with anti-PD-1 agents had developed cutaneous irAEs [10], accounting for the most frequently reported irAEs [10].

A wide range of cutaneous irAEs were described in the literature that appeared after varied latency periods of exposure to anti-PD-1 therapy [1, 3, 6]. Fortunately, the majority of skin reactions were of mild grades (grade I and II) that were either self-limiting or relatively manageable [1]. Table 2 summarizes the common cutaneous adverse events described in 253 patients who were treated with various anti-PD-1 agents in a review conducted by Simonsen et al [1]. Pigmentary changes/vitiligo were the most frequent cutaneous irAEs (58 patients), followed by psoriasis, bullous pemphigoid, and lichenoid dermatitis (33, 31, and 30 patients, respectively) [1].

Click to view | Table 2. Common Cutaneous irAEs Reported in 253 Patientsa Treated With Various Anti-PD-1 Agents per Review Conducted by Simonsen et al [1] |

The exact mechanisms of cutaneous irAEs remain poorly understood [1, 6]. Several theories were postulated to explain the pathophysiology of immune checkpoint inhibitors-induced skin toxicities [2, 3]. The most plausible theory is the presumed exaggerated response of effector T cells, which results in cytotoxic and inflammatory damage to cutaneous and subcutaneous tissues, partly because of the blockade of inhibitory PD-1/PD-L1 effects [8]. Dual use of an anti-CLTA-4 blocker with an anti-PD-1 agent increases the risk of irAEs [8]. Furthermore, combination therapy with anti-PD-1 agents was associated with both a higher risk of occurrence of cutaneous irAEs and a worsening clinical profile of skin toxicities (grade III and VI), as demonstrated from the phase III trial of augmented ipilimumab-plus-nivolumab therapy to treat metastatic melanoma [11].

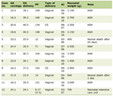

The occurrence of severe systemic cutaneous irAEs such as SJS/TEN is a clinical rarity [2, 4]. An extensive review published by Maloney et al [4] identified a total of 18 patients with SJS/TEN following treatment with different anti-PD-1 agents (pembrolizumab, ipilimumab, nivolumab, and atezolizumab) [4]. We conducted a comprehensive search to identify nivolumab-induced SJS and/or TEN cases (either as a monotherapy or combination therapy), which yielded 11 patients [12-22]. One patient was managed with dual therapy with ipilimumab, and one was treated with nivolumab after the failure of ipilimumab. Table 3 outlines baseline patient characteristics, latency onset, the clinical presentation of SJS/TEN, and outcome and management for each patient. Seven cases were SJS, while TEN was diagnosed in three cases [12, 13, 15], and one case was an SJS/TEN overlap in keeping with our reported patient [17].

Click to view | Table 3. A Literature Review of the Published Cases of Nivolumab-Induced SJS/TEN |

SJS/TEN rash onset ranged from 1 week [16, 20] to 4 months [14] with an average latency of 2 - 4 weeks. Interestingly, in the latter case [14], SJS rash appeared after eight cycles of nivolumab therapy in a similar pattern of delayed autoimmune diseases [14]. Furthermore, compared to other medications such as lamotrigine when SJS manifested within the first few days of drug exposure [4], a relatively long latency of nivolumab-induced SJS (few weeks) is observed, and this finding may be explained by the different pharmacokinetics profile of nivolumab which reaches the steady-state concentration after 12 weeks with a half-life of 25 days [23]. The lack of prodromal symptoms in our patient is in line with the reviewed literature that reported constitutional symptoms in three cases only [16, 17, 19].

Recall radiation dermatitis in association with SJS/TEN observed in the presented patient was described in similar two cases that were pre-medicated with radiotherapy [20, 21], and this phenomenon of the distinct distribution of rash over previous radiation sites may be related to a selective re-exposure of certain epitopes from radiation-damaged skin cells to locally hyperactive T cells [20].

SJS/TEN management entails a multidisciplinary team (critical care, dermatology, oncology, and infectious diseases) with an integral component of supportive care, preferably in a specialized burn unit for standard care of skin wounds [24]. Optimization of fluid balance, correction of electrolytes/micronutrient disturbances, and aggressive sepsis source control is necessary to minimize associated morbidities [24]. Early recognition of STS/TEN with immediate discontinuation of the offending agent (nivolumab) is essential to avoid the further dissemination of rash [14]. Nivolumab was the likely culprit of SJS in our case, as the calculated Naranjo algorithm was 7 which denotes a probable association [25] (Table 4). No trials of nivolumab rechallenge after SJS/TEN diagnosis were attempted in the available literature [4]. Immunosuppressive therapy with systemic steroids was associated with better outcomes of SJS, as all the seven cases of nivolumab-induced SJS (without TEN) had survived [14, 16, 18-22]. Furthermore, a recent meta-analysis has reported a beneficial role for cyclosporin (CsA) in SJS/TEN management, as CsA may block the cytotoxic T cells-induced epithelial cell injury [26]. TEN was associated with much worse mortality rates as all four patients with TEN died from polymicrobial sepsis and progression of the underlying malignancies [12, 13, 15, 17].

Click to view | Table 4. Calculated Adverse Drug Reaction Probability Scale (Naranjo Algorithm) in Our Case [25] |

Conclusion

The authors described a rare case of nivolumab-induced SJS/TEN in a patient with metastatic gastric adenocarcinoma that was successfully managed with immunosuppressive therapy and supportive care. Prompt clinical recognition of SJS/TEN, early discontinuation of nivolumab, and multidisciplinary management with critical supportive care in a specialized burn unit have contributed to the reasonable clinical recovery of our patient. A high index of clinical suspicion is warranted to identify SJS/TEN in patients treated with anti-PD-1 agents as SJS/TEN.

Learning points

The occurrence of SJS or TEN with nivolumab use is an exceedingly rare phenomenon that yet deserves serious attention due to the possible fatal outcomes associated with SJS/TEN.

Physicians should be aware of severe cutaneous adverse effects of anti-PD-1 agents, especially with their increasing use in modern oncology practice.

Early recognition of SJS/TEN and prompt discontinuation of nivolumab are warranted when SJS/TEN is suspected clinically.

Multidisciplinary management (involving critical care, nutrition services, dermatology, oncology, and infectious diseases) is essential to improving the outcome of SJS/TEN.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the Department of Intensive Care Unit at Saint Francis Presence Hospital for providing valuable input to this case presentation.

Financial Disclosure

The authors confirm that there is no funding to declare regarding the publication of this case report.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest regarding the publication of this case report.

Informed Consent

Informed written consent was obtained from the patient to write and publish their case as a case report with all accompanying clinical images.

Author Contributions

ES, PA, and DA contributed to conceptualizing and writing the first manuscript. AA, VB, KM, EA, and QZ contributed to editing the final draft. ES and DA performed the critical review. All authors were involved in the clinical management of the reported patient. All authors agreed to the final draft submission.

Data Availability

The authors declare that data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

| References | ▴Top |

- Simonsen AB, Kaae J, Ellebaek E, Svane IM, Zachariae C. Cutaneous adverse reactions to anti-PD-1 treatment-A systematic review. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(5):1415-1424.

doi pubmed - Chen CH, Yu HS, Yu S. Cutaneous adverse events associated with immune checkpoint inhibitors: a review article. Curr Oncol. 2022;29(4):2871-2886.

doi pubmed - Postow MA, Sidlow R, Hellmann MD. Immune-related adverse events associated with immune checkpoint blockade. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(2):158-168.

doi pubmed - Maloney NJ, Ravi V, Cheng K, Bach DQ, Worswick S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reactions to checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(6):e183-e188.

doi - Fakoya AOJ, Omenyi P, Anthony P, Anthony F, Etti P, Otohinoyi DA, Olunu E. Stevens - Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis; extensive review of reports of drug-induced etiologies, and possible therapeutic modalities. Open Access Maced J Med Sci. 2018;6(4):730-738.

doi pubmed - Wei SC, Duffy CR, Allison JP. Fundamental mechanisms of immune checkpoint blockade therapy. Cancer Discov. 2018;8(9):1069-1086.

doi pubmed - Gettinger SN, Horn L, Gandhi L, Spigel DR, Antonia SJ, Rizvi NA, Powderly JD, et al. Overall survival and long-term safety of nivolumab (Anti-Programmed Death 1 Antibody, BMS-936558, ONO-4538) in patients with previously treated advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2015;33(18):2004-2012.

doi pubmed - Guo L, Zhang H, Chen B. Nivolumab as programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor for targeted immunotherapy in tumor. J Cancer. 2017;8(3):410-416.

doi pubmed - Khoja L, Day D, Wei-Wu Chen T, Siu LL, Hansen AR. Tumour- and class-specific patterns of immune-related adverse events of immune checkpoint inhibitors: a systematic review. Ann Oncol. 2017;28(10):2377-2385.

doi pubmed - Hwang SJ, Carlos G, Wakade D, Byth K, Kong BY, Chou S, Carlino MS, et al. Cutaneous adverse events (AEs) of anti-programmed cell death (PD)-1 therapy in patients with metastatic melanoma: A single-institution cohort. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;74(3):455-461.e451.

doi pubmed - Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, Grob JJ, Cowey CL, Lao CD, Schadendorf D, et al. Combined nivolumab and ipilimumab or monotherapy in untreated melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(1):23-34.

doi pubmed - Vivar KL, Deschaine M, Messina J, Divine JM, Rabionet A, Patel N, Harrington MA, et al. Epidermal programmed cell death-ligand 1 expression in TEN associated with nivolumab therapy. J Cutan Pathol. 2017;44(4):381-384.

doi pubmed - Kim MC, Khan HN. Nivolumab-Induced Toxic Epidermal Necrolysis: Rare but Fatal Complication of Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor Therapy. Cureus. 2021;13(5):e15017.

doi - Dasanu CA. Late-onset Stevens-Johnson syndrome due to nivolumab use for hepatocellular carcinoma. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2019;25(8):2052-2055.

doi pubmed - Griffin LL, Cove-Smith L, Alachkar H, Radford JA, Brooke R, Linton KM. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) associated with the use of nivolumab (PD-1 inhibitor) for lymphoma. JAAD Case Rep. 2018;4(3):229-231.

doi pubmed - Gracia-Cazana T, Padgett E, Calderero V, Oncins R. Nivolumab-associated Stevens-Johnson syndrome in a patient with lung cancer. Dermatol Online J. 2021;27(3):13.

doi pubmed - Koshizuka K, Sakurai D, Sunagane M, Mita Y, Hamasaki S, Suzuki T, Kikkawa N, et al. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with nivolumab treatment for head and neck cancer. Clin Case Rep. 2021;9(2):848-852.

doi pubmed - Ito J, Fujimoto D, Nakamura A, Nagano T, Uehara K, Imai Y, Tomii K. Aprepitant for refractory nivolumab-induced pruritus. Lung Cancer. 2017;109:58-61.

doi pubmed - Salati M, Pifferi M, Baldessari C, Bertolini F, Tomasello C, Cascinu S, Barbieri F. Stevens-Johnson syndrome during nivolumab treatment of NSCLC. Ann Oncol. 2018;29(1):283-284.

doi pubmed - Shah KM, Rancour EA, Al-Omari A, Rahnama-Moghadam S. Striking enhancement at the site of radiation for nivolumab-induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Dermatol Online J. 2018;24(6):7.

doi pubmed - Rouyer L, Bursztejn AC, Charbit L, Schmutz JL, Moawad S. Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with radiation recall dermatitis in a patient treated with nivolumab. Eur J Dermatol. 2018;28(3):380-381.

doi pubmed - Nayar N, Briscoe K, Fernandez Penas P. Toxic epidermal necrolysis-like reaction with severe satellite cell necrosis associated with nivolumab in a patient with ipilimumab refractory metastatic melanoma. J Immunother. 2016;39(3):149-152.

doi pubmed - Sheng J, Srivastava S, Sanghavi K, Lu Z, Schmidt BJ, Bello A, Gupta M. Clinical pharmacology considerations for the development of immune checkpoint inhibitors. J Clin Pharmacol. 2017;57(Suppl 10):S26-S42.

doi pubmed - Lemiale V, Meert AP, Vincent F, Darmon M, Bauer PR, Van de Louw A, Azoulay E, et al. Severe toxicity from checkpoint protein inhibitors: What intensive care physicians need to know? Ann Intensive Care. 2019;9(1):25.

doi pubmed - Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, Sandor P, Ruiz I, Roberts EA, Janecek E, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1981;30(2):239-245.

doi pubmed - Ng QX, De Deyn M, Venkatanarayanan N, Ho CYX, Yeo WS. A meta-analysis of cyclosporine treatment for Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Inflamm Res. 2018;11:135-142.

doi pubmed

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.