| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 3, Number 2, April 2012, pages 89-93

Allograft Reconstruction for Reverse Hill-Sachs Lesion in Chronic Locked Posterior Shoulder Dislocation: A Case Report

Hester J Scheffera, c, Jaap J Quista, Arthur van Noortb, Dirk PH van Oostveenb

aDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Medisch Centrum Alkmaar, Alkmaar, The Netherlands

bDepartment of Orthopaedic Surgery, Spaarneziekenhuis, Hoofddorp, The Netherlands

cCorresponding author: Hester J Scheffer, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Medisch Centrum Alkmaar, Wilhelminalaan 12, 1815 JD Alkmaar, The Netherlands

Manuscript accepted for publication November 1, 2011

Short title: Allograft Reconstruction for Reverse Hill-Sachs Lesion

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc403w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Posterior dislocations of the humeral head are rare and often missed on initial presentation. Half of these injuries are associated with an impression fracture of the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head (reverse Hill-Sachs lesion). Several operative strategies have been described to treat this injury, but evidence based management strategies are lacking. We describe a case in which a young and active patient presented with a stiff and painful shoulder following a clavicle fracture 9 months earlier. MRI revealed a locked posterior shoulder dislocation and large reverse Hill-Sachs defect. Anatomic reconstruction of the humeral head was performed using a femoral head allograft to fill the defect. A year later the patient has a good shoulder function without pain or impairments in his daily activities. Posterior shoulder dislocation continues to be a “diagnostic trap”. This case reinforces the importance of radiographic axial and transscapular (Y) shoulder views to prevent missing the diagnosis. We state that, even in cases with delayed diagnosis and large humeral head defects, one should attempt to preserve the stability and function of the shoulder joint by restoring the normal anatomy of the humeral head. Femoral head allografting proves to be a suitable option. This case is unique in the combination of injuries, the long diagnostic delay and the encouraging functional results after femoral head allografting.

Keywords: Locked posterior shoulder dislocation; Reverse Hill-Sachs lesion; Anatomic reconstruction; Allograft reconstruction; Femoral allograft

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Posterior dislocations of the humeral head are rare, comprising only 2-4% of shoulder dislocations [1, 2]. They mostly occur secondary to violent muscle contractions associated with seizures, electric shock or (sports) trauma [3-5]. Half of these dislocations are associated with an impression fracture of the anteromedial aspect of the humeral head or “reverse Hill-Sachs lesion” [6, 7]. Unfortunately, the injury is overseen in 60% at first presentation [8].

There are no evidence-based management strategies concerning the humeral head impaction, but different surgical options are a non-anatomic reconstruction such as a transfer of the subscapularis tendon [9] or the minor tubercle [10] into the defect and subcapital rotational osteotomy of the proximal humeral head [11]. Other options are cancellous auto- or allografting [8] and arthroplasty [6, 12].

Recently, fresh osteochondral allografts have been proven safe and efficacious to restore the articular surface in weightbearing joints. This preserves the normal anatomy and has therefore been advocated as a joint-preserving alternative to total or hemiarthroplasty [13-15].

The purpose of this paper is to report the results of reduction and reconstruction of the humeral head with a bone allograft after a 9-month diagnostic delay in a young and active patient with a locked posterior shoulder dislocation and subsequent impression fracture involving 40% of the articular surface, and an ipsilateral midshaft clavicular fracture.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

A 30 year-old, healthy, active male was referred to our clinic with left shoulder complaints. Nine months earlier, he had fallen from his racing bicycle, directly onto his shoulder, for which he had visited the emergency department. Due to an obvious left clavicle deformity, only clavicle radiographs were made, showing a midshaft clavicle fracture that was treated conservatively with a sling. During follow-up in our hospital, radiographs showed the consolidated clavicle fracture. Despite this consolidation and intensive physiotherapy, the patient continued to suffer a poor shoulder function. He was referred to our department with the diagnosis frozen shoulder.

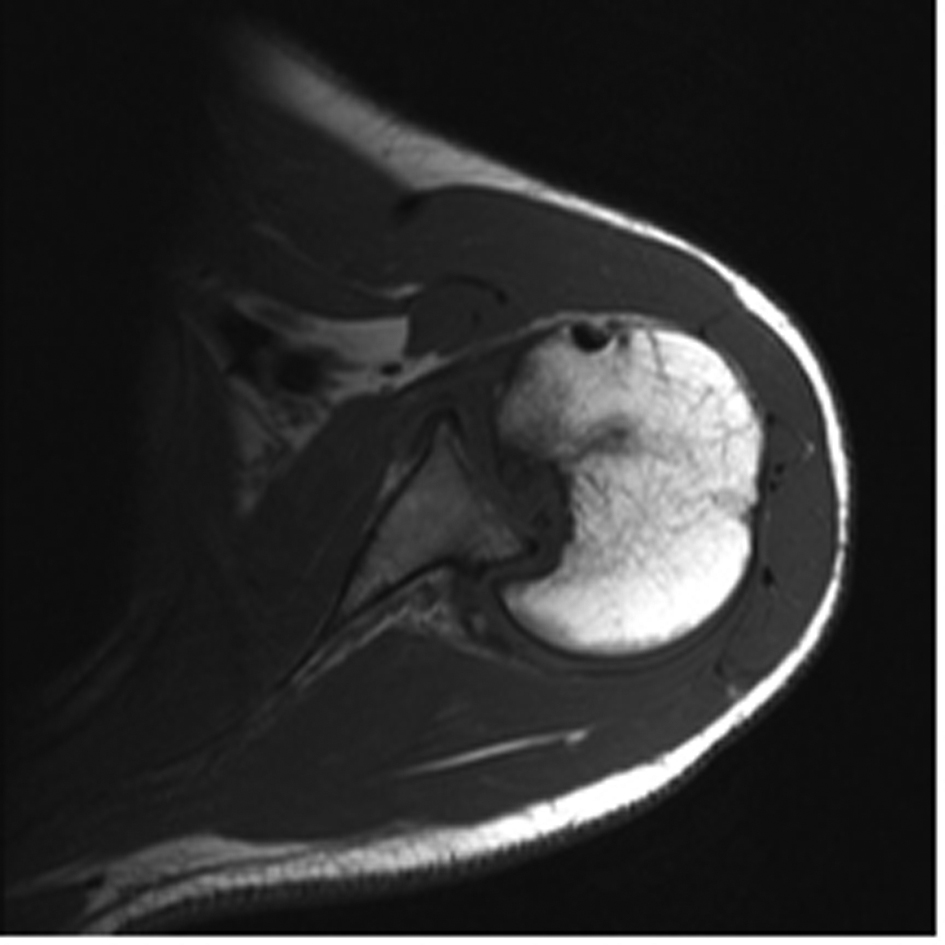

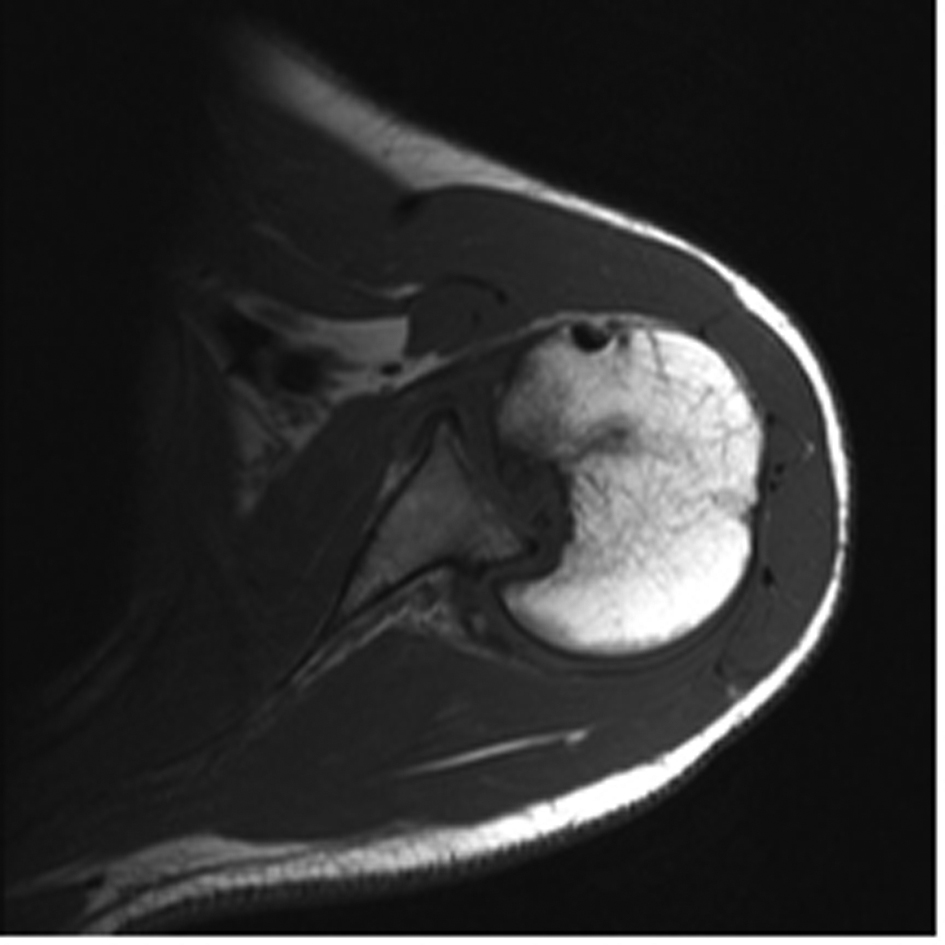

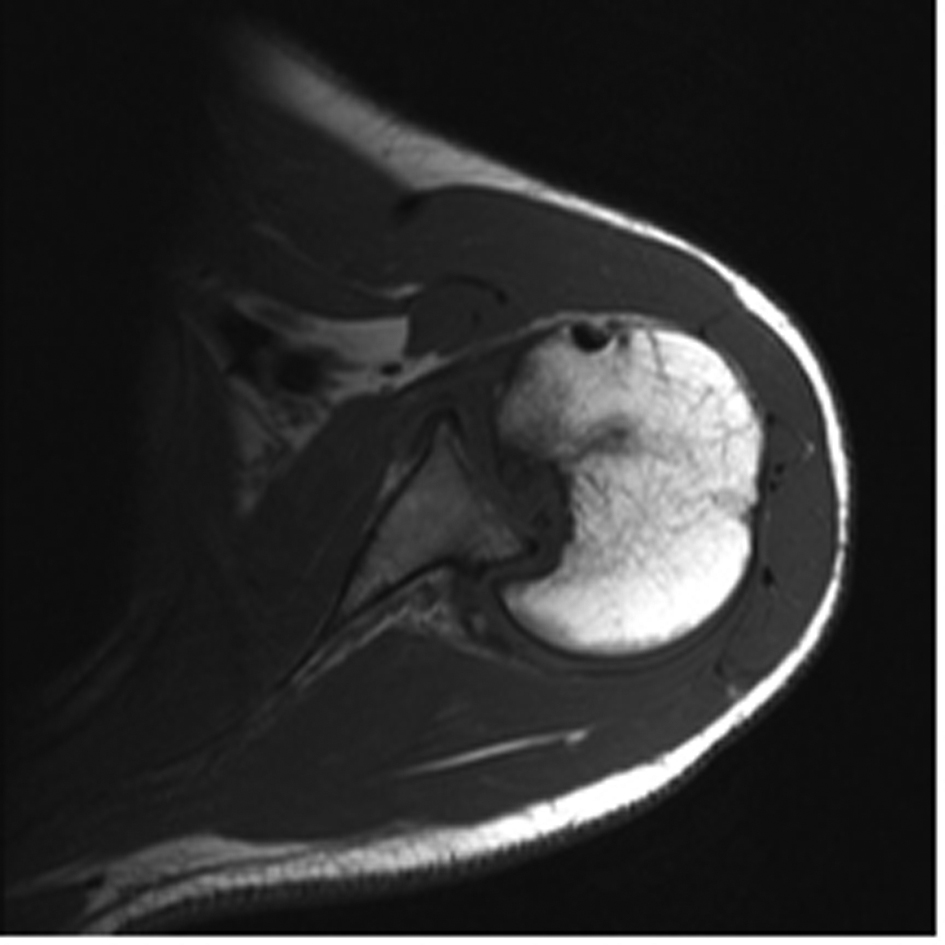

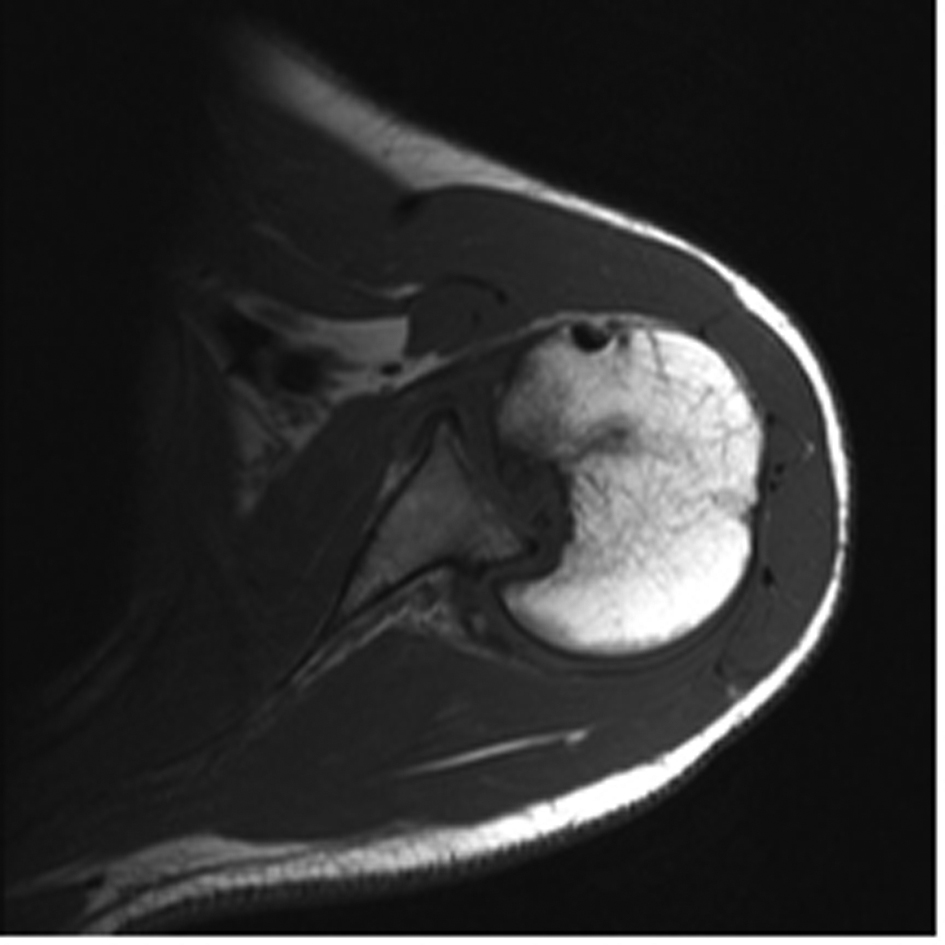

On physical examination, the left clavicle was shortened. There was no obvious distortion of the shoulder contour. His range of motion was restricted with 0o external rotation, 70o abduction and 90o forward elevation. There was no neurological deficit on examination. Plain radiographs showed a partially consolidated clavicle fracture and a deviant position of the humeral head in the shoulder joint, suspect for a posterior luxation (Fig. 1). Subsequent magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scanning revealed a locked posterior shoulder dislocation and a large reverse Hill-Sachs defect, measuring approximately 40% of the articular surface of the humeral head (Fig. 2).

Click for large image | Figure 1. Anteroposterior radiograph showing a partially consolidated clavicle fracture and a deviant position of the humeral head, suspect for posterior dislocation. |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Preoperative MRI scan of the right shoulder showing a locked posterior shoulder dislocation and a large reverse Hill-Sachs defect. |

Operative technique

The patient was placed in beach chair position under general anaesthesia and an interscalene-block. The deltopectoral approach was used. There were no lesions of the rotator cuff, but due to damage of the long head of the biceps tendon, a tenodesis was performed. After performing a subscapularis tendon tenotomy and subsequent arthrotomy, the posterior capsule was released to reduce the humeral head. The glenoid and the remaining humeral cartilage were remarkably well, but there was no vital cartilage in the large reverse Hill-Sachs defect.

A cryopreserved femoral head allograft was carefully measured to fill the defect and to restore the original sphericity of the femoral head, using two cancellous screws. Hereafter, the shoulder showed a broad external and internal rotation with no apparent instability, after which the incision was closed.

Postoperative radiographs showed the reduced humeral head with restoration of the sphericity (Fig. 3). The shoulder was immobilized in a shoulder brace in 30 degrees of abduction and neutral rotation for 4 weeks, followed by a sling for several weeks. During this period, the splint was removed for passive external rotation exercises only. After six weeks, muscle resistance exercises were started.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Postoperative radiograph of the right shoulder showing the reduced humeral head with restoration of the sphericity. |

Functional outcome evaluation

At follow-up 6 months postoperatively, functional outcome was assessed using the Constant and Murley score [16]. The absolute Constant Score was 77 points, whereas the “relative Constant Score”, a percentage based on average values using reference parameters out of a healthy age and gender related control group, [17] was 97 points. This decrease in functional outcome was entirely based on a mild reduction in strength and range of motion; subjectively, the patient was free of pain and had no restrictions in his daily activities. He had resumed his work full time at follow-up. He had also started riding his bicycle without complaints. CT scanning confirmed incorporation of the allograft into the former defect zone and a regular contour of the humeral head with only a small intra-articular step-off (Fig. 4).

Click for large image | Figure 4. CT scan 6 months postoperative confirming incorporation of the allograft and regular contour of the humeral head. |

At most recent follow-up, 12 months postoperatively, the absolute Constant Score had improved from 77 to 89 points, with only a slight impairment in range of motion remaining, and normal strength. Overall, the patient stated to be very satisfied with the result.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Due to the rarity of incidence of posterior-fracture dislocations, their occasional occurrence creates a “diagnostic trap” for the unwary surgeon [9]; due to incomplete clinical and radiological evaluation at the emergency department, the injury is overseen in 60% at first presentation.

In order to prevent missing this diagnosis, firstly, adequate clinical examination is essential. Particularly asymmetry between the shoulders and an inability to externally rotate the shoulder should arouse suspicion. Secondly, a transscapular (Y) and axial radiographic projection should always be performed. The radiographic findings on the anteroposterior projection may be so subtle that a posterior dislocation is missed. However, with the addition of axillary and Y views the dislocation will be quite obvious. An axillary projection requires some abduction at the shoulder, which can be very painful after an injury. To overcome this problem, alternatively, a Velpeau axillary view can be obtained [18]. In our hospital, the Velpeau projection has become the routine projection together with the anteroposterior projection in trauma to the shoulder.

Our case was complicated by a concomitant clavicle fracture that had apparently masked the dislocation on initial examination (although passive external rotation should still have been possible) and was assumed to have caused a frozen shoulder. Only 9 months later, the correct diagnosis was made, a delay that rarely has been encountered [6, 13].

The difficulty to treat this injury lies within the fact that in a chronic dislocated humeral head, vascularisation is at risk, which may eventually lead to avascular necrosis. Moreover, the defect can become more extended, provoking instability, osteoporosis and osteoarthritis [1, 8]. Thus, apart from the extent of the humeral head injury and the age of the patient, the choice of treatment also depends on the interval between injury and diagnosis [8, 19].

Although the reverse Hill-Sachs defect is considered to be the main component of recurrent shoulder instability in posterior shoulder dislocation, there are no standardized treatment options [5]. Only a few series, each with a limited number of patients, have been described.

In 1952, McLaughlin was the first to treat the impression fracture, by transferring the subscapularis tendon into the defect [9]. Later, Hughes and Neer modified McLaughlin’s procedure by transferring the lesser tuberosity with its attached subscapularis tendon into small defects [10]. Rotational subcapital humeral osteotomy was introduced by Weber in 1984 [11]. However, all these techniques alter the humeral joint anatomy, leading to a limitation of internal rotation and possibly complicating future prosthetic reconstruction. Anatomic reconstruction with elevation of the depressed cartilage and subchondral buttressing with bone cement [20] or with spongiotic auto- or allograft [8] is possible in fresh defects where the articular cartilage has been impressed but not destroyed [6, 21]. For defects involving more than 40% of the articular surface, the treatment of choice has long remained total or hemiarthroplasty [6, 10, 12].

In younger patients like ours, all effort should be made to preserve the normal sphericity of the humeral head, thereby restoring the stability and function of the shoulder. This makes osteochondral allografting a logical option, provided that the residual bone is in good condition [22]. Thus, in spite of the risk associated with a long diagnostic delay and the large size of the defect, this is what we decided on. Even if the procedure would fail, prosthetic reconstruction should be simple because the skeletal anatomy is not distorted [1, 5, 8, 13].

To our knowledge, only few published studies have performed femoral allografting in posterior fracture-dislocation. In 1996, Gerber and Lambert [13] introduced this method and reported good results in three cases with a mean Constant Score (CS) of 73 at mean final follow-up of 65 months and one bad result where avascular necrosis of the humeral head developed seven years postoperatively (CS 34). In 2010, Diklic et al. [6] retrospectively evaluated the outcome of 13 patients at a mean follow-up of 54 months (41 to 64). Their mean CS was 86.8 (43 to 98) in 12 patients with a 25 to 40% defect. One case developed avascular necrosis with collapse of the allograft in a 60% defect.

Compared to these studies and considering our relatively short follow-up period (with the shoulder function being likely to further improve), the functional outcome is encouraging. However, the follow-up period is too short to determine the final outcome of the treatment with respect to possible graft-failure or the development of osteoarthritis. These results will become evident with the passing of time.

Conclusion

In this case report the successful treatment of a locked posterior shoulder dislocation with a large reverse Hill-Sachs defect with femoral allografting is described. It illustrates how this injury continues to be a “diagnostic trap” [9]; the correct diagnosis was masked by a clavicle fracture for 9 months. It reinforces the importance of complete radiographic evaluation, including axial and transscapular views for all shoulder trauma to prevent missing this diagnosis. Although evidence-based management strategies are lacking, we state that shoulder anatomy should be preserved where possible, even in cases with delayed diagnosis and large humeral head defects.

This case is unique in the combination of injuries, the long diagnostic delay and the encouraging functional results after femoral allografting.

Financial Disclosure

None.

| References | ▴Top |

- Martinez AA, Calvo A, Domingo J, Cuenca J, Herrera A, Malillos M. Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head associated with posterior dislocations of the shoulder. Injury. 2008;39(3):319-322.

pubmed doi - Walch G, Boileau P, Martin B, Dejour H. [Unreduced posterior luxations and fractures-luxations of the shoulder. Apropos of 30 cases]. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1990;76(8):546-558.

pubmed - Brown RJ. Bilateral dislocation of the shoulders. Injury. 1984;15(4):267-273.

pubmed doi - Kelly JP. Fractures complicating electro-convulsive therapy and chronic epilepsy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1954;36-B(1):70-79.

pubmed - Khayal T, Wild M, Windolf J. Reconstruction of the articular surface of the humeral head after locked posterior shoulder dislocation: a case report. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2009;129(4):515-519.

pubmed doi - Diklic ID, Ganic ZD, Blagojevic ZD, Nho SJ, Romeo AA. Treatment of locked chronic posterior dislocation of the shoulder by reconstruction of the defect in the humeral head with an allograft. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2010;92(1):71-76.

pubmed doi - Edelson G, Kelly I, Vigder F, Reis ND. A three-dimensional classification for fractures of the proximal humerus. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):413-425.

pubmed doi - Bock P, Kluger R, Hintermann B. Anatomical reconstruction for Reverse Hill-Sachs lesions after posterior locked shoulder dislocation fracture: a case series of six patients. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2007;127(7):543-548.

pubmed doi - Mc LH. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1952;24-A-3:584-590.

pubmed - Hughes M, Neer CS, 2nd. Glenohumeral joint replacement and postoperative rehabilitation. Phys Ther. 1975;55(8):850-858.

pubmed - Weber BG, Simpson LA, Hardegger F. Rotational humeral osteotomy for recurrent anterior dislocation of the shoulder associated with a large Hill-Sachs lesion. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66(9):1443-1450.

pubmed - Griggs SM, Holloway GB, Williams GR Jr, Iannotti JP (1999) Treatment of locked anterior and posterior dislocations of the shoulder. In: Disorders of the shoulder: diagnosis and management. Philadelphia, Lippincott Williams & Wilkins pp 335-339.

- Gerber C, Lambert SM. Allograft reconstruction of segmental defects of the humeral head for the treatment of chronic locked posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78(3):376-382.

pubmed - Mankin HJ, Doppelt S, Tomford W. Clinical experience with allograft implantation. The first ten years. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1983;17(4):69-86.

pubmed - McDermott AG, Langer F, Pritzker KP, Gross AE. Fresh small-fragment osteochondral allografts. Long-term follow-up study on first 100 cases. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1985;19(7):96-102.

pubmed - Constant CR, Murley AH. A clinical method of functional assessment of the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1987;21(4):160-164.

pubmed - Fialka C, Oberleitner G, Stampfl P, Brannath W, Hexel M, Vecsei V. Modification of the Constant-Murley shoulder score-introduction of the individual relative Constant score Individual shoulder assessment. Injury. 2005;36(10):1159-1165.

pubmed doi - Silfverskiold JP, Straehley DJ, Jones WW. Roentgenographic evaluation of suspected shoulder dislocation: a prospective study comparing the axillary view and the scapular 'Y' view. Orthopedics. 1990;13(1):63-69.

pubmed - Checchia SL, Santos PD, Miyazaki AN. Surgical treatment of acute and chronic posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7(1):53-65.

pubmed doi - Engel T, Lill H, Korner J, Josten C. [Bilateral posterior fracture-dislocation of the shoulder caused by an epileptic seizure - diagnostic, treatment and result]. Unfallchirurg. 1999;102(11):897-901.

pubmed doi - Chalidis BE, Papadopoulos PP, Dimitriou CG. Reconstruction of a missed posterior locked shoulder fracture-dislocation with bone graft and lesser tuberosity transfer: a case report. J Med Case Reports. 2008;2:260.

pubmed - Cicak N. Posterior dislocation of the shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86(3):324-332.

pubmed doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.