| Journal of Medical Cases, ISSN 1923-4155 print, 1923-4163 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Med Cases and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.journalmc.org |

Case Report

Volume 4, Number 8, August 2013, pages 523-525

Cluster Headache and Pituitary Prolactinoma

Bengt Edvardsson

Department of Neurology, Faculty of Medicine, Skane University Hospital, S-221 85 Lund, Sweden

Manuscript accepted for publication May 28, 2013

Short title: Cluster Headache and Pituitary Prolactinoma

doi: https://doi.org/10.4021/jmc1379e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Cluster headache (CH) is a primary headache by definition not caused by any known underlying structural pathology. However, symptomatic cases have been described, for example, tumors, particularly pituitary adenomas, malformations, and infections/inflammations. The evaluation of CH is an issue unresolved. A 46-year-old man presented with a 5-month history of side-locked attacks of an excruciating stabbing and boring left-sided pain located in the orbit. He satisfied the revised International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for CH. His medical and family histories were unremarkable. A diagnosis of CH was made. The patient partially responded to symptomatic treatment. Owing to the relatively late onset of CH an enhanced magnetic resonance imaging was ordered to rule out an underlying lesion. It was performed after 1 month and displayed a pituitary adenoma. Evaluations revealed a prolactinoma. After treatment with bromocriptine, the headache attacks resolved completely. Although I cannot exclude an unintentional comorbidity, in my opinion, the co-occurrence of a prolactinoma with unilateral headache, in a hitherto headache-free man, points toward the fact that in this case the CH was caused or triggered by the prolactinoma. The headache attacks resolved completely after the bromocriptine treatment and the patient also remained headache free at the follow-up. The response of the headache to sumatriptan and other typical CH medications does not exclude a secondary form. Symptomatic CHs responsive to this therapy have been described. Associated cranial lesions such as tumours have been reported in CH patients and the attacks may be clinically indistinguishable from the primary form. Neuroimaging, preferably contrast-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging should always be considered in patients with cluster headache despite normal neurological examination. Late-onset cluster headache represents a condition that requires careful evaluation. Prolactinoma can present as cluster headache.

Keywords: Cluster headache; Pituitary adenoma; Prolactinoma; Magnetic resonance imaging; Symptomatic

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Cluster headache (CH) is a primary headache, by definition not caused by any underlying structural pathology and belonging to the group of trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias [1]. CH is the most frequent syndrome in this group. The characteristic symptoms are strictly unilateral head pain (mainly around orbital and temporal regions) and associated ipsilateral cranial autonomic features. The headache usually lasts 45 to 90 minutes, but can range between 15 and 180 minutes. A circannual and circadian pattern is typical. Although uncommon, symptomatic cases of CH have been described, for example, tumors, particularly pituitary adenomas, malformations, and infection/inflammation [2]. The question whether patients with CH should undergo neuroimaging to exclude a causal underlying structural lesion is unresolved. Symptomatic CH due to prolactinoma is rare, although reported [2]. I here report a case of prolactinoma, the symptoms of which fully comply with the criteria of cluster headache [1]. Therefore, the importance of accurate neuroimaging in CH patients is emphasized.

| Case Report | ▴Top |

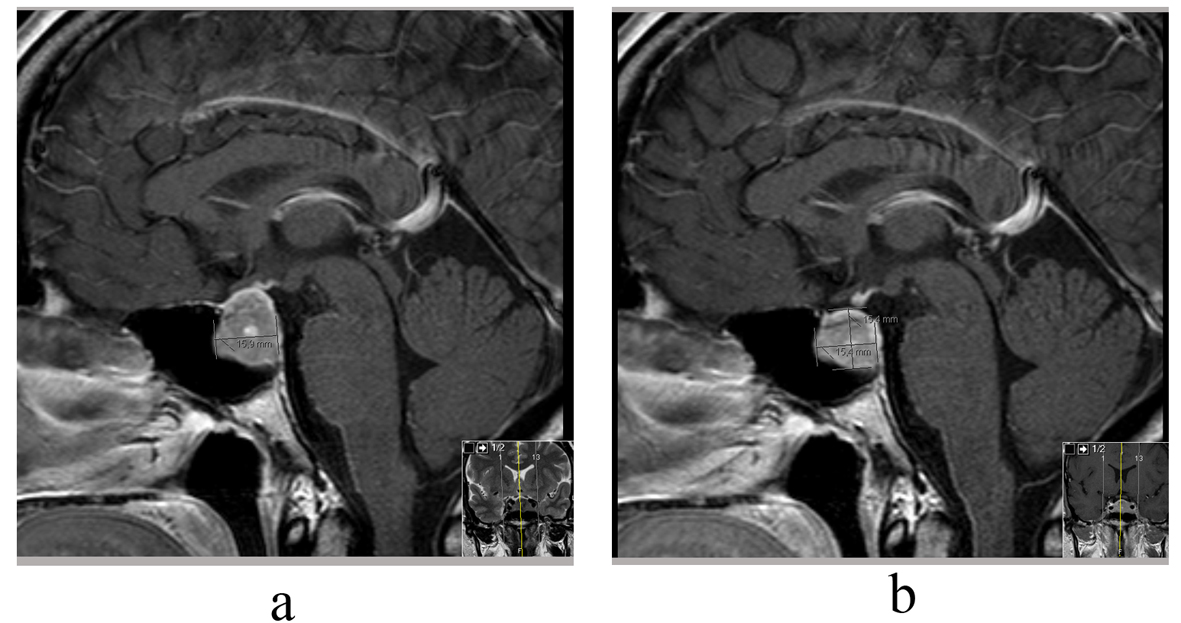

A 46-year-old man presented with a 5-month history of side-locked attacks of an excruciating stabbing and boring left-sided pain located in the orbit. The attacks were associated with nasal obstruction, conjunctival injection, restlessness, nausea and photophobia/phonophobia. No continuous background pain was identified. The duration of the attacks was about 40 - 50 minutes and the frequency 3 per 24 hours, 3 to 4 days a week and they also occurred during the night. There was no history of headache. His medical and family history was otherwise unremarkable. He was not on any medications and used no drugs. Vital signs, physical examination, and neurological examination were normal. Routine laboratory testing was normal. He satisfied the revised International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for CH. A diagnosis of CH was made and subcutaneous sumatriptan as well as oral sumatriptan were prescribed along with oral verapamil 240 to 480 mg daily. The patient responded partially to the treatment with relief within 15 to 20 minutes (subcutaneous sumatriptan) and the attacks were reduced in frequency within 7 days (1 attack/d). A follow-up was planned. Owing to the relatively late onset of CH an enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) was ordered to rule out an underlying lesion. It was performed after 1 month and displayed a pituitary adenoma (Fig. 1a). The serum prolactin was significantly elevated (3,000 µg/L, normal range < 15 µg/L). The remainder of the pituitary function was normal. A pituitary prolactinoma was diagnosed and the patient was prescribed bromocriptine, half a 2.5 mg tablet taken at bedtime. The dose was gradually increased every 3 to 7 days up to 7.5 mg. The patient’s headache remained in the improved state with only sporadic headache attacks at follow-up after 2 months. Visual fields were normal. An MRI scanning performed after about 4 months displayed reduction in tumour volume (Fig. 1b). The patient now reported that the headache attacks had completely resolved.CH treatment was discontinued. He remained headache free and had not experienced any headache attacks at follow-up after 5 years despite discontinuation of CH treatment. Serum prolactin levels remains slightly elevated.

Click for large image | Figure 1. (a) MRI sella, Sag T1 demonstrating a pituitary adenoma (prolactinoma); (b) MRI sella, Sag T1 demonstrating a reduction in tumour volume. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The case study highlights a patient with CH responding to treatment. Evaluation revealed a pituitary prolactinoma. The patient satisfied the revised International Classification of Headache Disorders criteria for CH [1]. Although I cannot exclude an unintentional comorbidity, in my opinion, the co-occurrence of a pituitary prolactinoma with unilateral headache, in a hitherto headache-free man, points towards the fact that in this case the CH was caused or triggered by the prolactinoma. The headache attacks resolved completely after treatment of the prolactinoma.

The response of the headache to sumatriptan and other typical CH medications does not exclude a secondary form [3, 4]. Associated cranial lesions such as tumours have been reported in CH patients and the attacks may be clinically indistinguishable from the primary form [3, 5]. Mainardi et al [2] identified 156 secondary cluster-like headache (CLH) cases published from 1975 to 2008. They found in the review that vascular pathologies, for example, intracranial aneurysms and dural fistulas were the first cause of secondary CH, followed by tumours and inflammatory/infectious diseases. Pituitary adenomas accounted for 3% of secondary CH cases. Prolactinomas were the most common tumour of the pituitary adenomas.

The pathophysiology of CH is not well known. The most widely accepted theory is that primary CH is characterized by hypothalamic activation with secondary activation of the trigeminal-autonomic reflex, probably by a trigeminal-hypothalamic pathway [1]. The exact pathophysiology in our case is unknown. A structural lesion may cause autonomic imbalance, resulting in periodic fluctuations in the activity of the autonomic nervous system, ultimately leading to an attack-wise presentation of the symptoms. Differences in the individual threshold for triggering the parasympathetic trigeminal reflexes may also play a role [6, 7]. A number of cases of symptomatic CH reported have had sellar/parasellar abnormality as well as in this case. The sympathetic, parasympathetic and sensory fibres of the trigeminal nerve gather as a plexus in the sinus cavernosus/hypophyseal region. Thus, nerves in this region appear to be of importance to produce symptoms of CH [1].

Attempts have been made to define red flags indicating a secondary cause when cluster-like headache appears for the first time [2]. Compared with primary CH, secondary CH presents at an older age (about 42 y). A late onset represents a condition that requires careful evaluation [2]. The authors of that study also emphasize in their report that, at first observation, 50% of patients with secondary CH presented as cases fulfilling the criteria for CH, perfectly mimicking CH. Therefore, the likelihood that a secondary cause is responsible for a clinical picture mimicking a primary CH, albeit low, should always be considered [2].

This opinion is in accordance with the review by Favier et al and Wilbrink et al [5, 6] who recommend neuroimaging in all patients with trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. MRI is the preferred procedure for imaging in CH cases because of its greater sensitivity to vascular disease, tumor, demyelinating disease, and infection/inflammation [2, 6].

Conclusions

CH might be the presenting symptom of a pituitary prolactinoma even in typical forms of that headache. Contrast-enhanced MRI including different techniques should always be considered in patients with CH. Late-onset CH represents a condition that requires careful evaluation.

Source(s) of Support

None.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that he has no conflict of interest.

| References | ▴Top |

- Olesen J, Tfelt-Hansen P, Welch K M A, Goadsby PJ, Ramadan NM, eds. The Headaches. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006:1169.

- Mainardi F, Trucco M, Maggioni F, Palestini C, Dainese F, Zanchin G. Cluster-like headache. A comprehensive reappraisal. Cephalalgia. 2010;30(4):399-412.

pubmed - Ad Hoc. Committee on Classification of Headache of the National Institutes of Health. Classification of headache. JAMA. 1962;179:717-718.

- Testa L, Mittino D, Terazzi E, Mula M, Monaco F. Cluster-like headache and idiopathic intracranial hypertension: a case report. J Headache Pain. 2008;9(3):181-183.

doi pubmed - Favier I, van Vliet JA, Roon KI, Witteveen RJ, Verschuuren JJ, Ferrari MD, Haan J. Trigeminal autonomic cephalgias due to structural lesions: a review of 31 cases. Arch Neurol. 2007;64(1):25-31.

doi pubmed - Wilbrink LA, Ferrari MD, Kruit MC, Haan J. Neuroimaging intrigeminal autonomic cephalgias: when, how, and of what? CurrOpin Neurol. 2009; 22(3):247-253.

doi pubmed - Straube A, Freilinger T, Ruther T, Padovan C. Two cases of symptomatic cluster-like headache suggest the importance of sympathetic/parasympathetic balance. Cephalalgia. 2007;27(9):1069-1073.

doi pubmed

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Medical Cases is published by Elmer Press Inc.